For nearly three decades, Dara Moskowitz Grumdahl has cultivated a parasocial friendship with her readers, telling us where to go, what to do, and how to eat, in essays and reviews infused with her signature enthusiasm and infectious wonder. The Upper Midwest is, after all, a place where the socially conditioned response to a compliment is, “I got it on sale,” and we need a New York-transplant-turned-Minnesotan to poke around and remind us that—hey—what we’ve got here is actually pretty spectacular.

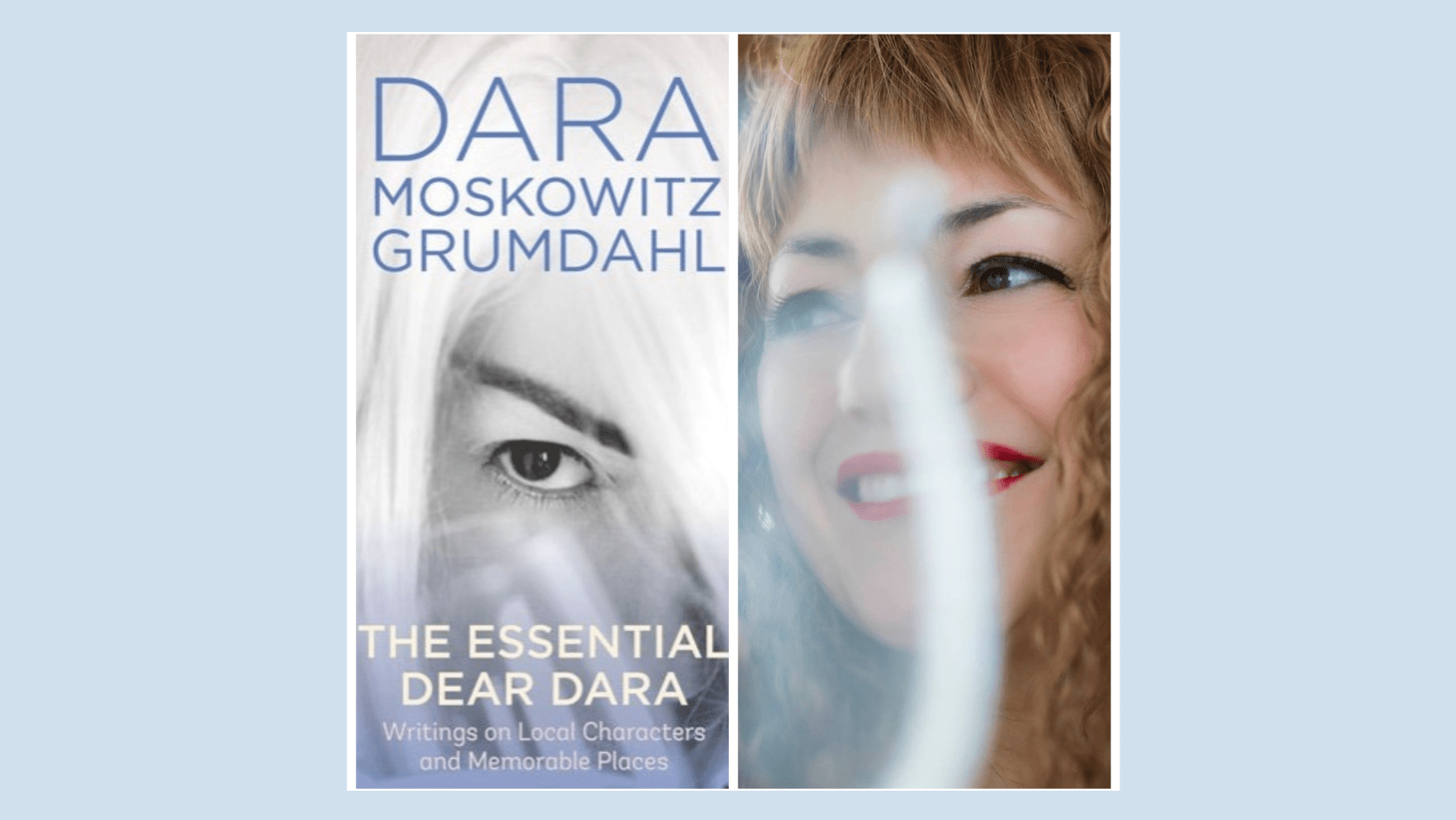

Dara’s second book, The Essential Dear Dara: Writings on Local Characters and Memorable Places (September 6, 2023, Minnesota Historical Society Press, 304 pages) spans her expansive career in print and digital media, from the shuttered alt-weekly City Pages, to ad-heavy glossies, to a defunct 1990s-era internet relic called Microsoft Sidewalk. The collection includes a shockingly vulnerable introduction; old favorites, like her 1996 City Pages lutefisk takedown and the epic 2015 Minneapolis St. Paul Magazine review in which Dara encouraged Gavin Kaysen to live up to his full potential; and some witty, sparkling pieces nearly lost to digital ether.

On a sultry late-August afternoon, Dara poured Racket a crystal stem glass of aperitif and sat down in her backyard with her pets: a piebald, bell-collared cat and a shaggy, pony-tailed dog. While the cicadas buzzed, we spoke about her writing process, her Champagne Barbie alter ego, her distaste for happy memoir fables, and lutefisk’s State Fair revenge.

You have a very YOLO zest for minutiae, coincidence, and serendipity. How do you cultivate that? Is that your personality? Do you work on it?

That’s my personality. If I say I really like life, that sounds stupid, but I really like life, all of the details of life. Paying attention to life, as sort of my meditative way of engaging with things, being okay with things. There are times when I have felt that it is a handicap because I can just get so zonked out on how amazing things are, like, this puddle! This oil slick! Like, oh look at it! And then, it’s like, what are you doing, it’s an oil slick in the gutter. You are ridiculous. There’s no chemicals in your system, what are you doing.

There are times—years, decades—when I was trying to train myself out of that because I thought it was a failing. When I was maybe 40, I started leaning into it a lot more because I like it. There’s a thing in writing called a fictive dream: the accretion of details makes you believe that you’re inside this thing. I think that’s how human beings are. You pull out those details and people can feel it in their own brains and bodies and experiences.

In the book, you reference many writers that have inspired you. You write about sleeping with your copy of Wind in the Willows when you were a child.

Later I would sleep with a copy of a Katherine Mansfield anthology. I went around Europe for months and I had one book. I would read it again and again.

When I was a 20-something, I was obsessed with a Martin Amis book called Money. Just like, how does this work? If you shake it, like the gears will fall out and you can find out how it works. I must have fallen asleep with that one hundred times, trying to make sense of it, and never quite got it.

I was very sad that he died. I interviewed him for City Pages. He was coming through town on a paperback tour, which makes no sense. And a fax came into the office: Does anyone want to meet Martin Amis at the Marquette Hotel? And I said, “I’ll be there in one minute!” Now he’s dead and I can’t ever tell him, “You influenced me so much.” Some of it, I don’t think, ages that well. But he has this crackling ability to manipulate language and be funny and dark at the same time, which to me is the highest thing you can do.

Which contemporary authors do you like to read?

I’m one of the many George Saunders superfans. I love Lorrie Moore, of course. Zadie Smith. And Danez Smith, who lives in town, is an incredible poet. Smith is a genius; they’ll be our T.S. Eliot once their body of work starts to accrete. I love Kelly Barnhill. And Kate DiCamillo is probably our Tennessee Williams. Some of those middle-grade children’s authors in town are world-class brilliant. DiCamillo’s Tale of Despereaux made me weep two times, three years apart. It is the most beautiful, moving thing.

I really liked the instructional pieces in your book, like the “How to Interview Anyone” chapter. You talk a little bit about your process, but can you tell me about the super boring stuff: Do you write at the kitchen table? Longhand or typing? Multiple drafts?

All of the above. When I’m writing fiction, I typically write longhand on big yellow pads, in ink. Then I will transfer it to the computer. And sometimes I’ll do another draft by hand on a yellow pad. For a restaurant review, I will typically compose on the computer and I will do an extremely stupid outline, which is like: intro, this quote, mention this dish, mention that, pull in this, outro. And then if I don’t have the brute outline, I will go for a walk. If I’m walking I will dictate into notes. Sometimes I’ll start walking out the door and eventually I will reach a point that it usually comes to me.

So you’re talking into the voice recorder?

Usually. I can remember certain stories. There was this poet that I wrote about once and I had no way in. It felt like everything I would say was trite or repeating myself. And I started walking, and four miles away, all of a sudden I was like, "That’s it!" That was an extreme case.

Once I have the general shape in my mind, the beginning, middle, and end. And that whole form didn’t occur to me as the important parts of writing until I was, like, 40. When I was at City Pages I used to write the beginning, the end, and then just basically connect the two. I do something else now that’s a little more complicated. But just learning how to do that was big and got me far.

When were you writing for Microsoft Sidewalk? Was that a gig while you were at City Pages?

Kind of. I graduated from Carleton and moved up here. I had two minimum-wage jobs, working at a phone bank and cocktailing at Chi-Chi’s downtown. And I just did as much writing as I could. Those years, the summer of 1992 to when I got put on staff at City Pages, I cannot tell you how much of a hustle and a scramble it was.

I perceived myself to have a bad back because all I did was hunch over a computer keyboard and type all the time. I didn’t walk, I didn’t cook. I just typed and typed. And some of those years I made, like, seven grand. So I was working as hard as I could and making no money. I taught myself to write and I feel very good about that, but it wasn’t smart and I don’t recommend anyone else do that. It was bonkers.

How do you save your work? You describe finding a printout of that Microsoft Sidewalk piece. Do you print everything out?

At the time, you needed clips. I remember my very first City Pages piece. I did a book review that was maybe 75 words, one inch by two inches. I had a friend who worked at Kinko’s. Everyone in 1993 had a friend at Kinko’s. And I cut it out, taped it down on some white paper, and my friend Jeff got me 20 copies for free.

I would put that stuff in a basket in the basement. There’s a pile of the City Pages stuff. I kept a hard copy of every one, which I am so glad. For this book, I literally sat at my dining room table and retyped them.

Since clouds became a thing, everything I write now is automatically backed up. For some of the more modern pieces, like “The Donut Gatherer,” I had the raw draft just sitting in my Dropbox. It’s not organized or anything at all.

So when your papers go to the library archives at Carleton someday, what will the archivist be dealing with?

They’ll be very much surprised. There’s a lot of stuff.

I would be surprised if anyone wants it. I’ve been working on a novel for nine years. I have a pact with a friend that, if I get hit by a bus, she has to find it and do anything with it, like print it out and leave it at bus stops.

What’s the novel about?

It’s my Great American Novel. It’s a feminist story about a woman who finds that she is disappearing and she doesn’t want it to be happening. And it’s the comedy of everything she does to try and prevent herself from disappearing. And everyone around her doesn’t believe it’s happening.

You asked about living writers that I care about. I forgot to mention Murakami. He’s a huge influence on me, just like, you can do anything you want. There! You have permission.

When I read the Introduction to The Essential Dear Dara, I was shocked. Have you written about your childhood trauma before? What is it like to put that out into the world?

Never. That was the hardest thing I ever wrote. It felt like I was gouging out my own flesh with a spoon. My family, we just fought about whether any of that happened. You say, "This is happening to me," and they say, "No it’s not." The next thing that’s happening is, “You’re bad, you’re dangerous, you’re a liar.” And, you know, I’m tough and I’m feisty. I’m a survivor. And that’s really the story of how I got to Minnesota.

I’ve played a role in this culture, which is Champagne Barbie. That was my shorthand for myself: I just fell out of Sex and the City and I came here to be fun and amazing! There was a time when I felt really unseen or misunderstood. But I also felt like it was a useful role; people need to dream.

It wasn’t until the pandemic and therapy. I’ve been in therapy forever. I would tell my therapist I was having recurring nightmares. For three years we talked it through, and she was like, "What if this recurring thing, that you constantly think about, did happen?" So it was years of getting to that. And it was freeing. I feel like I had this bubble at the top of my throat where I couldn’t say a lot of true things because I was keeping that one thing in.

It was the summer of 2022 where I was, for the first time, saying, “I didn’t make this up.” This recurring fight that I had with my family: They were not right and I was not wrong. This is a thing that happened.

I feel like it’s sort of necessary. We have this myth in the culture that people are not physically abused, and people are not sexually abused. And if something happens to you, that it’s unusual or aberrant. But if you dig into the statistics, it’s solidly something like 20% of women are sexually assaulted. Or half of people are victims of violence in the home. It’s normal, and I am one of the tough people that pretended it never happened and you blaze forward. But there’s a certain amount of evolution and personal growth and achievement that you can never—it’s like that Jack LaLane thing. Jack LaLane was in the back of comic books and his idea was, you could build your muscles by pushing against, like isometric exercises. I got to a point where I was pushing ahead, trying to speak my truth, and an enormous part of myself was pushing back, and I’m not getting anywhere. I’m stuck here.

So I had never written about it before. Everyone feels like I’m their friend, or their cousin, or their interesting neighbor. How about we just say who the real people here are? I think people will be happy to hear about it. Because they’ll know me better and have more understanding and connection. To everything, to the world and their community. If there are people who don’t want it, they can just turn past it. They’re probably not going to be great friends anyway.

I’ve lived through the age of memoir and I never felt like I wanted to do that. First of all, where I grew up, it was common. Everyone was getting the shit beat out of them all the time. It was not an “oh, poor me” situation. I’m allergic to that, “And now’s a happy ending. It made me stronger.” I don’t like that. That’s not authentic to reality or lived experience. I’m not going to do it. So that’s my stubbornness. There’s always that pressure to have a socially acceptable ending. I don’t like it. I think if you go through the body of my work, I like to say things that are fresh. And true. Not phony. I hate phony.

That makes me think of Holden Caufield.

Very, very influenced by Holden Caufield.

It’s clear from your essay collection that you’re a generalist. You call yourself a writer about nouns. But you also acknowledge that many people regard you as a food writer.

I am a food writer. Not only a food writer.

As you’ve watched the food scene here mature over the past couple of decades, what have you observed as its biggest growing pains?

Real estate prices. Minneapolis in 1995, rents were really cheap. Cheap to live in, cheap for musician studios, cheap for restaurants. And now it’s really disgusting how many empty storefronts there are. If I could wave a magic wand, I would change the way that we do taxes in the great state of Minnesota. I would make a tax penalty for landlords who are sitting on empty space. If they can’t rent a space, they should have to let the market determine the value of the space. Look at any place, any street in the Twin Cities at this point. People are getting evicted and the restaurants are sitting empty.

The landlords get to write it off on their taxes. They say, “I missed, whatever, $24,000 in rent payments so I take that off my income.” So they’re making money by not renting these spaces. They should be forced to bear the real market conditions that the rest of us have to. Rents are the real limiting factor. That is the main growing pain and will continue to be the main growing pain.

What solutions do you foresee in the restaurant industry? The service sector, in general, has all these service fees and tip prompts.

We should have single-payer health care. It is the biggest strangler to entrepreneurial business development on every front. If we had government-backed health care, with an actual government-backed safety net, businesses of every kind would be launching left, right, and center. Everyone is constrained by healthcare costs. Every restaurant is constrained by healthcare costs. It’s not about the food whatsoever! It’s entirely about healthcare costs. If we had Medicare for All, if we had single payer, if we had any other way. It’s obscene that we don’t.

Are you going to start a newsletter?

I may. The whole, how to market to people who care about my writing that’s not restaurant reviews, is an open question in my life right now. Do I do a Substack and talk about the things that I am interested in, the things that are happening in my life? I only want to write about restaurants for my wonderful employer, Minneapolis St. Paul Magazine. People should subscribe.

I do not have the money or the personal inclination to spend six nights out a week at prestige restaurants. I’m a restaurant critic because it’s a job. I love serving the community and my magazine. People are always asking me, “When are you going to fly to Tokyo and eat all the ramen?” When someone else foots the bill! Things I do in my free time include reading books. I’m a reader and a writer. I’m not a restaurant evaluation machine.

Food writing is very expensive. Very time consuming. So people should support their local publications, such as Racket and Minneapolis St. Paul Magazine, if they want to see restaurant reviews in the world. We just did the State Fair and, my god, between my eating around and Steph March and the rest of the team, if you add up how much money we spent, it’s crazy. Crazy!

One thing I enjoy about your writing is how you describe people’s appearances. You’re very good at eye color. How would you describe your own eye color? This is a silly question.

I would say milk chocolate brown, or light brown. You’re writing this. What would you say?

I would agree. I’m distracted by your hair.

That changes a lot. You gotta have fun, man.

Is that for the book promotion?

No, I’ll probably end up wearing different wigs for the book promotion. I have a whole Batgirl armoire of wigs.

Are the wigs for restaurant reviews?

No, I do the opposite. I usually look like myself in restaurants. And when I go on TV or on stage, then I put on a wig and try to bring a show. I started doing that at City Pages because it always seemed so doofy, like, “Hey, come talk about pie on KARE-11.” It feels like a patriarchal game that women can’t win. "We want you to look like a Barbie doll, but we don’t want you to have any of the support that the Barbie dolls have to look like Barbie dolls. Then we’re going to judge you against the Barbie dolls. And don’t get any older!"

It felt like an extremely bullshit game from the jump. The wigs were kind of my way of doing my own fun thing and I still like it. It’s still funny to me. It engenders a certain amount of privacy, which I also like.

Thanks for speaking with me. It’s thrilling to interview a local celebrity.

I feel very much not like a celebrity. Like, yesterday I was sitting under a branch on a rock at the State Fair. There was this thing where they rehydrated lutefisk with hoisin sauce. I was trying to figure it out, trying to figure it out, and all of a sudden I went to sit down and I was like, this is my 27th year doing new foods at the State Fair. Is this the year I throw up? So I don’t feel like a celebrity. I feel like an interesting weirdo. A local notable.