Thanks to my penchant for collecting vintage cookbooks, I have discovered a parallel universe.

In the inspired-by-true-events movie version, this discovery occurs in my dignified home library stocked with handsome leather-bound volumes. In the real-life version, my collection is housed in an IKEA room divider, and my well-worn cookbooks are sourced from my local Buy Nothing Facebook group and thrift stores. A cracked binding might fall open to a beloved brownie recipe spattered with melted chocolate. The pages are dog-eared and marked up with the graceful, looping penmanship schools stopped teaching decades ago.

I occasionally cook from my vintage books, but mostly I keep them around to get a glimpse into the food culture of previous eras. A last-minute dinner menu for when your husband unexpectedly brings home his war buddy, vegetable Jello salads, references to “exotic” cuisines—it’s nostalgic and illuminating and horrifying, sometimes all at once.

But within the pages of my vintage cookbooks lurks more than meatloaf recipes and tips for throwing a children’s birthday party in your rumpus room. Recently, I found something mysterious, something intriguing, something that has forever altered my perception of reality.

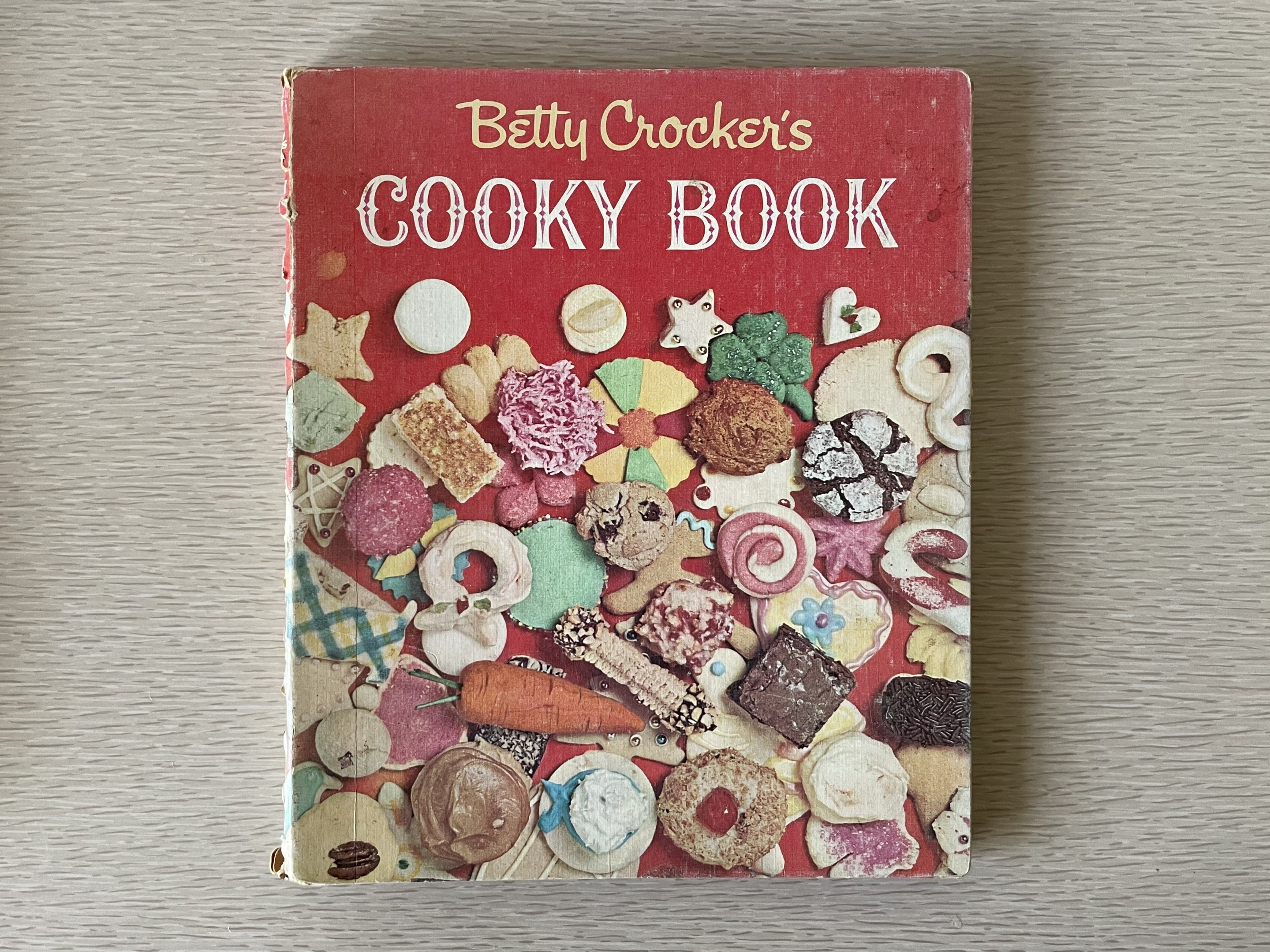

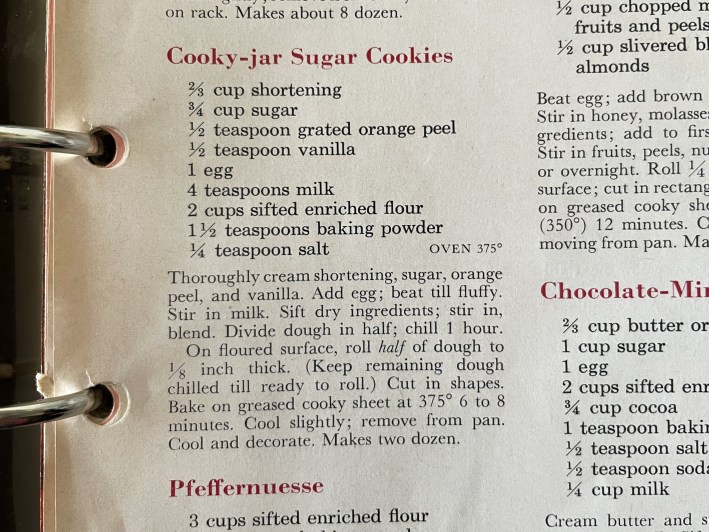

I first spotted it in the Better Homes and Gardens New Cook Book from 1953. Then I saw it in The Successful Hostess’ Guide to Delectable Cookies published in 1966. It’s present in 1960’s The I Hate to Cook Book (a discontented housewife’s manifesto penned by Peg Bracken that deserves its own deep dive). And, most obviously, it stared me right in face from the cover of the 1963 Betty Crocker’s Cooky Book. That’s not a typo: “cookie” is spelled with a y.

Cooky.

Did you have the disconcerting experience of discovering that the Berenstein Bears books of your childhood were actually about the Berenstain Bears? Depending on which Internet rabbit hole you fall down, it's either evidence of the Mandela Effect (a phenomenon in which large groups of people share a false memory—for instance, the erroneous belief that activist Nelson Mandela died in prison) or it’s proof of a parallel universe where the so-called Berenstain Bears really are the Berenstein Bears. A similarly weird discrepancy exists in my vintage cookbook collection: It used to be perfectly acceptable to spell cooky with a "y" instead of an "ie."

What’s even stranger is that no one seems to recall this alternate spelling. I've spent more time that I care to admit delving into the cooky-with-a-y parallel universe, or as I have taken to calling it, the Cookyverse. Aside from Ebay listings for Betty Crocker’s Cooky Book and a few mentions on blogs and Reddit along the lines of “Why the hell is cooky spelled with a y in this vintage cookbook?” there's very little in the way of cooky scholarship. My sole lead was a YouTube recording of the presentation “Koekje, Cooky, or Cookie? A History of American Christmas Cookies” given by food historian Sarah Wassberg Johnson for the Poughkeepsie Public Library District in 2022.

From that presentation, I learned that U.S. cookies hearken back to Dutch baking traditions in New Netherland (now New York). The first written reference to “cookie” dates to 1703, and the term is derived from the Dutch word koekje, which translates to “small cake.” Eager to learn more, I called Wassberg Johnson to get a historical perspective on where cooky with y came from and where it went.

“Spelling was not really codified in American history until relatively late—lots of Americans spelled things phonetically,” she says. "As to why cooky with a y falls out of favor, it’s not super clear. Cookie with an ie is closer to the Dutch spelling of koekje—je is a diminutive in Dutch, and it makes a ‘ye’ sound.”

Wassberg Johnson explains that throughout the late 1700s and early 1800s, there was a concerted effort to define an American identity separate from European culture. Noah Webster’s 1828 American Dictionary of the English Language was an influential attempt to do that with spelling—we can thank Webster for American spellings of words like “favor” and “defense” that differ from their British counterparts. “It actually would be really interesting to see what cookie spelling Noah Webster used in his dictionary,” Wassberg Johnson muses.

Thanks to Google Books, I was on it. I tracked down a digitized version of the 1828 first edition of Webster’s dictionary and there it was: “COOKY: small cake, moderately sweet.” Webster was on Team Cooky-with-a-y! The father of American lexicography inhabited the Cookyverse!

In her presentation, Wassberg Johnson set up a Google Ngram line graph to compare the frequency of various cookie spellings in published works available via Google Books, and I created a similar graph to track the prevalence of cookie versus cooky from 1700-2019. The spellings are tied until about 1900, and cooky takes the lead in 1910. However, the y spelling falls behind in 1917 and never recovers.

By the 1950s, cookie was clearly the dominant spelling, with twice as many written references to “cookie” compared to “cooky.” So why was an antiquated spelling still being used in prominent titles like Betty Crocker’s Cooky Book?

“In the mid [20th] century, there was a colonial revival,” Wassberg Johnson says. “It really lasted from the 1920s until the Bicentennial. There was an interest in baking colonial and old-fashioned recipes, and I’m guessing that's the reason for the more old-fashioned spelling—there was an interest in hearkening back to previous eras. There was an interest in pioneer culture, the colonial period, the Founding Fathers. You see more unique, historic spellings popping up.”

Wassberg Johnson referred to Betty Crocker’s Cooky Book as “the last, most famous cooky with a y,” and I reached out to General Mills to get some intel on Cooky Book history. They responded with a polite note that they were “unable to help given other business priorities right now.” Possibly true, or possibly they fear that acknowledging the Cookyverse will unleash dark forces and cause the collapse of our cookie with an ie universe.

I was able to track down some Cooky Book background thanks to Susan Marks’s Finding Betty Crocker, which relies heavily on primary sources from the General Mills corporate archives. Apparently Betty Crocker’s Cooky Book is a revised, expanded, hardcover version of the 1948 recipe booklet “Betty Crocker’s Picture Cooky Book.” Through my own research, it appears General Mills maintained the “cooky” spelling through the Cooky Book’s 23rd printing in 1978, and then a revised edition titled Betty Crocker’s Cookie Book was published in 1980. In Finding Betty Crocker, Marks notes that General Mills re-released the original Betty Crocker’s Cooky Book in 2002. Those reproductions remain readily available, if you want to purchase your own evidence of the Cookyverse.

If you’re too grounded in your cookie with an ie reality for my Cookyverse theory, you can think about cooky with a y as an example of how things that we assume are fixed are actually pretty mushy. Spelling was subjective for most of American history, and to some extent, it still is. There is no official authority governing American English. The New Yorker is infamous for quirky spellings like coöperation and travelling. At some point in the mid-2010s, without even realizing it, I switched from e-mail to email and stopped capitalizing “internet.” Norms can shift, bit by bit, a letter or two at a time, and we can play a role in changing them.

It’s actually kind of inspirational. My vintage cookbooks are premised on upholding mid-century conformity and rigid gender norms—but the chaos of the Cookyverse still crept in.