For a guy who’s brought the world some of its most beloved animated images over the past four decades, Hayao Miyazaki has a grim view of his art. In The Wind Rises, which was intended as the Studio Ghibli master's final film in 2013, Miyazaki saw himself in Jiro Horikoshi, the visionary Japanese aeronautical designer whose apolitical focus on problem-solving allowed him to design his nation’s WWII warplanes without a second thought. Now, in The Boy and the Heron (the Japanese title translates as the less fairy-tale-ish, more ethically rigorous “How Do You Live?”), the filmmaker’s stand-in is an ancient wizard of sorts who regrets fashioning a crumbling alternate universe beset by unforeseen calamities.

I want to be careful here. It’s hard to resist decoding Miyazaki’s animated fables, but that’s a fraught venture—the images and moments have the shape of symbolic content, but they refuse to be reduced to mere allegory. The most fanciful beings are literally themselves and many other things besides. Complicating matters, Miyazaki’s heroes rarely complete a linear quest—what appear initially as side quests somehow become the main goals as the plot advances. Unspoken taboos are unknowingly violated, with rules and logic revealed on a need-to-know basis. The films have the narrative spontaneity of a bedtime story and the protean geography of a dream.

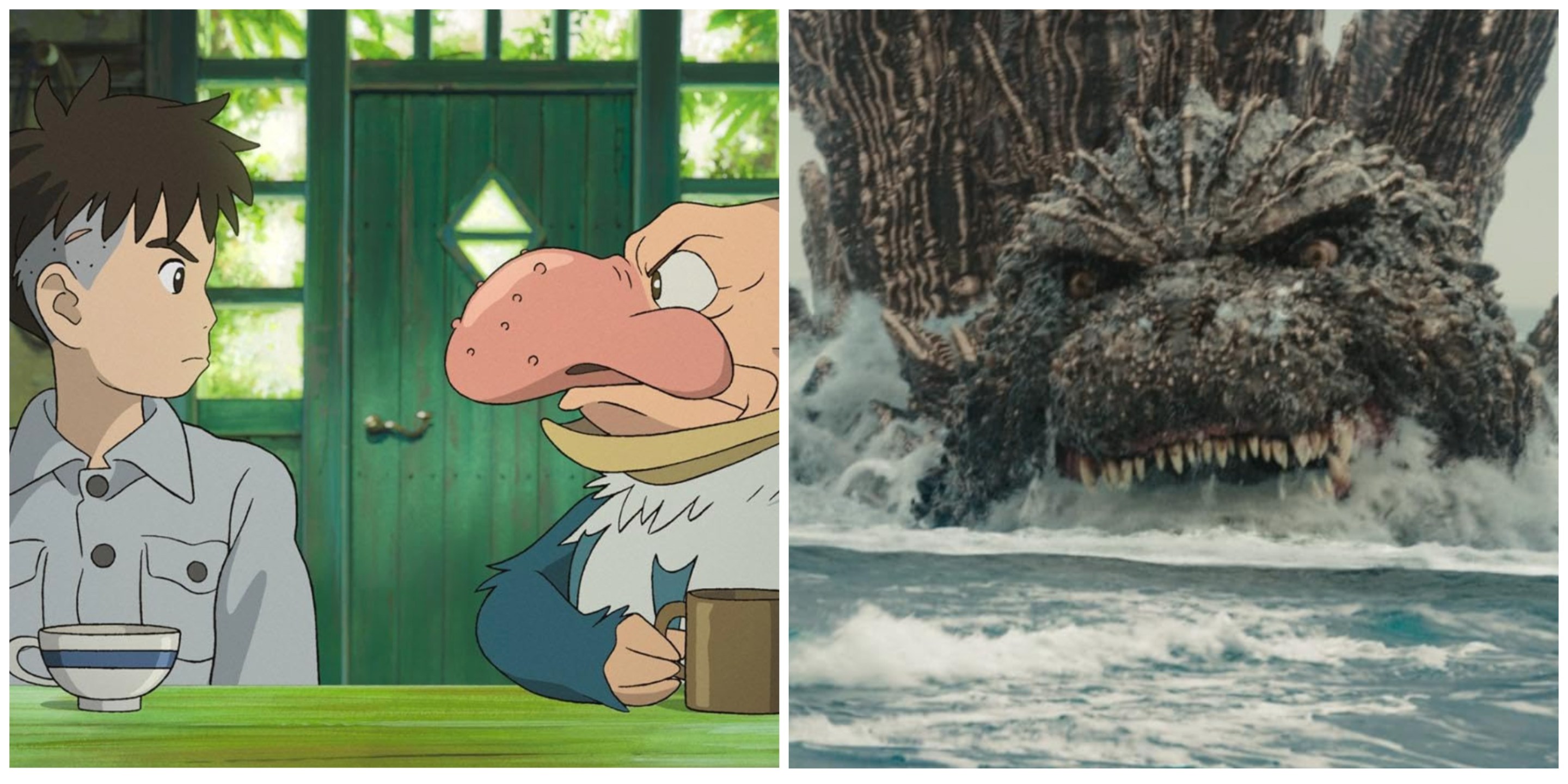

In The Boy and the Heron, Miyazaki doesn’t toss us into that dreamscape straightaway; instead he slowly, almost hesitantly leads us in. Mahito (no, for the tenth time, not “Mojito,” autocorrect) is a boy haunted by memories of his mother’s death in a fire. During WWII, his family relocates to the country, to an estate populated by grannies whose noggins have expanded to bobblehead proportions, as often happens to elderly women in Miyazaki’s films. A gray heron begins to pester Mahito, slowly revealing a grotesque face concealed within his beak, telling the boy that his mother isn’t dead, that she lives in the forgotten tunnels underneath the estate that lead to a mysterious tower.

As is typical for Miyazaki (how many times will I use some variation of that phrase in this review?) the other world that Mahito enters is cosmically off-balance and the pleasures and perils it offers are all delightful to behold. The most wondrous are the shmoo-like warawara, who inflate after eating fish guts and rise up to the other world to become human souls. But there are also pelicans who gobble the warawara like Pac-Man pellets, and giant, ravenous parakeets rule the tower, brandishing carving knives and cleavers. Ghost ships loom forlornly in the distance, and shades drift past in canoes, hoping the living will give them food.

There are so many beautiful set pieces here—the way the flames Mahito rushes into to save his mother seem to fuse with his body without burning, the luminous rise of the Warawara to the heavens—and there are smaller indelible moments too, like when Mahito crawls crablike into the shadows so his father doesn’t know he’s eavesdropping. In other words, it looks exactly like you want a Miyazaki movie to look.

With the guidance of the untrustworthy heron, Mahito searches for his stepmother-to-be Natsuko, who is nearly identical to his mother and has also disappeared into the tower. He’s accompanied solely by one of the grannies, Kiriko; after the two are separated, she rejoins him in the guise of a fisherwoman, who puts him to work rowing her boat and slicing upon the giant fish she catches. Eventually, Mahito must face his great-granduncle, who transformed the tower into what it is, and of whom we’re told “He was a very smart man. But he read too many books and he went mad.” Relatable.

“We must try to live,” characters repeat throughout The Wind Rises, quoting Paul Valéry. How Do You Live? asks the title to this follow up. Quite a question coming from an 82-year-old, and perhaps one Miyazaki wishes he’d asked himself sooner. Miyazaki, like Mahito, moved during the war from Tokyo to the country, where his father, like Mahito’s, operated a factory that built warplanes. It’s tempting to say as the great-granduncle confronts the boy here that the filmmaker, in his aged form, is revisiting the choices he made in his youth.

Curiously, Mahito is a bit earnest and bland a hero—”a good boy,” as he’s called more than once. (Spirited Away might not be the masterpiece it is if its protagonist, Chihiro, hadn’t been a bit of a whiny brat.) Mahito’s one truly dark moment comes when, after getting into a fight at a new school, he smashes a stone into the side of his head—maybe to make his injuries more believable or in a fit of self-loathing. It hints at a murkier interior life than we see here, reminiscent of Miyazaki’s insistence on seeing himself as a force of malice.

I’m not the first to say that The Boy and the Heron is Miyazaki’s The Tempest, but it’s worth repeating. For this film, Miyazaki famously unretired, and it wasn’t his first time. (Characteristically, he called his decision to return to moviemaking “pathetic.”) If The Wind Rises felt like a finale, The Boy and the Heron feels like an encore, a coda, a curtain call, a monologue from a great artist assuring us that this time, really, he is leaving the stage for good. His charms are all o’erthrown—for now, at least.

Unlike Miyazaki, Godzilla will never retire. He’s way too profitable. Godzilla Minus One, the thirty-somethingth appearance of Tomoyuki Tanaka’s scaly creation, set a new first-week U.S. box office record for a Japanese live-action film last month. With The Boy and the Heron arriving as the biggest film in the U.S. this past (admittedly slow) week, a trendspotter could say we’re experiencing a Japanese film boomlet—though I don’t exactly expect Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Monster to get a bump from that this weekend. Not unless the title fools some folks into expecting kaiju.

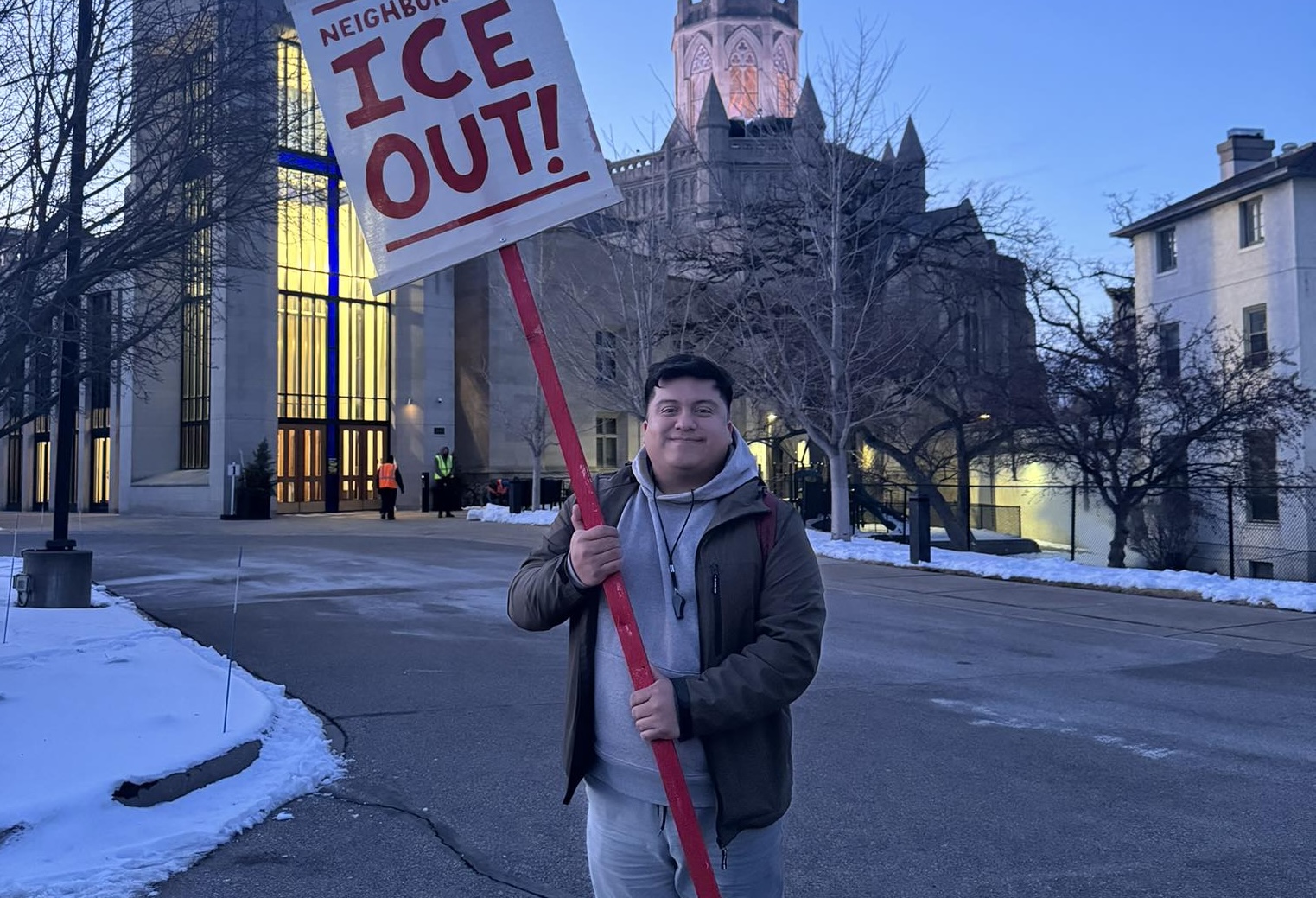

If Miyazaki’s films are resistant to a single interpretation, Godzilla is the biggest, loudest metaphor on Earth, reflecting the shift in Japanese anxieties over the past 70 years with about as much subtlety as his foot landing on the citizens of Tokyo. In the standard Godzilla origin story, nuclear testing disturbs the slumbering prehistoric behemoth, who arises as an imaginary stand-in for the unimaginable suffering of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But in Godzilla Minus One, the creature has stalked Japan throughout history, as though for writer/director Takashi Yamazaki he’s some inner demon that the Japanese people must come together and defeat to purify their national spirit.

We first see the mighty lizard here in 1945, with Japan on the verge of defeat. A kamikaze pilot named Kōichi Shikishima (Ryunosuke Kamiki) has landed on Odo Island, claiming engine trouble but in reality fleeing battle (and certain death, of course). An already guilt-ridden Shikishima chokes when the time comes to machine-gun Godzilla into oblivion, and he’s broken by the sight of the other soldiers being chomped, flung, and crushed.

And that’s the last we see of the scaly menace for a bit. As you may have heard, Godzilla Minus One tells “a human story.” We spend years with Shikishima, who returns to find his town in ruins and his neighbors condemning him for not dying bravely in battle. He takes in a young woman (Minami Hamabe) who is caring for an abandoned baby, and he supports this makeshift family by working as a minesweeper, though he remains emotionally distant. As part of a four-man crew that ventures out in a small wooden boat, he fires a mounted gun to explode the bombs left submerged after the war. Still, Godzilla—and his own cowardice—haunt Shikishima’s dreams.

This human-scaled approach hardly makes for as effective a postwar drama as some have said—it feels like more of a nice gesture than a real story. But it does provide a workable narrative framework for Yamazaki’s ideas about Japan. He gives us the sense of a country that’s just crawled out of its wreckage only to get knocked back on its ass; the heroes of Godzilla Minus One meet the threat with a mood of “shit, not again.” The U.S. can’t or won’t help (their presence would roil the Soviets, they claim) and the Japanese government has been stripped of its defenses under the terms of surrender.

And so it’s left to The People, armed with a little technological know-how and a lot of pluck, to defend the homeland. Just as Shikishima is haunted by survivor’s guilt, the men fighting Godzilla—former soldiers defeated in war—are exhausted. But this one last battle, it appears, allows the men to redeem themselves. Yamazaki has made something like a kaiju Rambo—the Japanese get to win this time.

Now let’s get to the important part: How’s Godzilla? Oh, he’s scary as hell. He’s nimbler than usual, his tail whipping with ferocity and velocity, and though the Bikini Atoll tests didn’t awaken him, they did mutate him, giving him awesome powers like nuclear breath. Yamazaki gets how to build anticipation: His Godzilla powers up before he goes nuclear, and before he appears the fish he’s been hunting float up to the surface of the sea. Godzilla, of course, levels Ginza as it has never before been leveled. But wisely, Godzilla Minus One allows a creature who rises from the depths of the sea to show what he can do on his own turf—or his own surf, I guess. There’s a nail biter of a ship chase, and at sea is where the final battle occurs as well.

Can he be stopped? Well. Without giving too much away here, let’s just say that anyone who’s seen a movie or two knows what happens when there’s a Plan A and a Plan B, as well as a last-ditch Plan C that’s rejected as too dangerous. The final battle allows for a shot at redemption, while rejecting past notions of sacrifice and suggesting that committing to building a new life is more honorable than dying for a cause.

I’m no Godzilla connoisseur, and there are many experts who can better place Godzilla Minus One in the context of the old boy’s canon. So take this as a review from someone who went in skeptical. I’ve always been a little jealous of the folks who got to see Godzilla for the first time in 1954, or even in 1956, unaware of what they (and Japan) were in for. While we can never recapture that initial response, Godzilla Minus One confronts us with a creature that’s so fearsome he seems born anew.

GRADES:

The Boy and the Heron: A-

Godzilla: B

The Boy and the Heron and Godzilla are now playing in area theaters.