The Bell Museum's move from Minneapolis to St. Paul is the stuff of legend. Massive taxidermied mammals were hoisted by crane through the air; hundreds of carefully constructed dioramas were transported from one city to the other.

(Minnpost has a wonderfully headlined story from 2018—"Bell on Wheels"—all about the incredible undertaking.)

The move from its funky art deco building to its current state-of-the-art space at 2088 Larpenteur Ave. W. also provided a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to really look at the Bell's collection—all 150+ years of correspondence, notes, clippings, and more— to create a book that could serve as an “annotated bibliography” of the natural history museum, says Lansing Shepard.

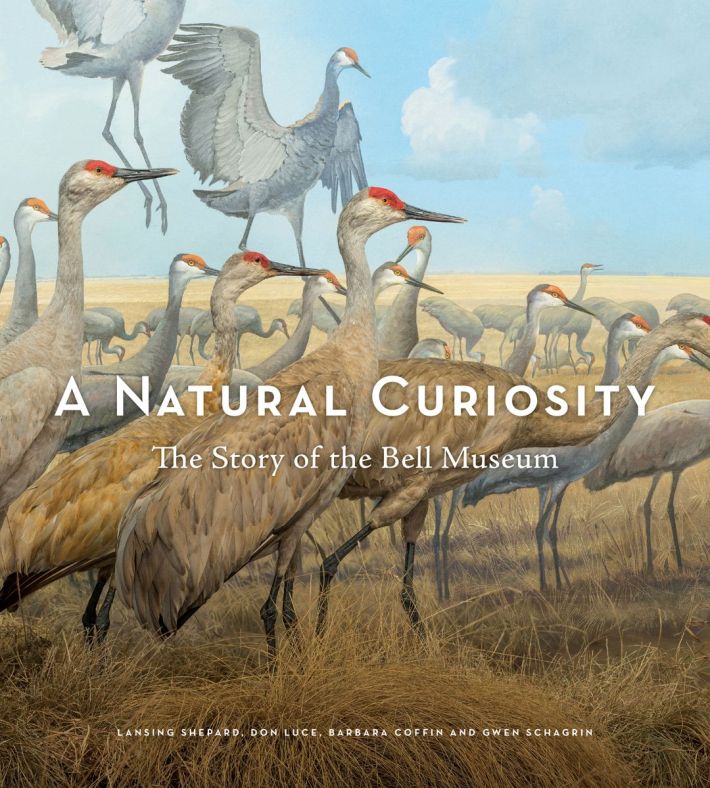

“Because nobody had even come close to trying,” says Shepard, co-author and chief writer of A Natural Curiosity: The Story of the Bell Museum (available now from the University of Minnesota Press).

Along with Bell Museum curator of exhibits Don Luce, former head of media productions Barbara Coffin, and Gwen Schagrin, who's worked in research, design, and production at the museum since '92, Shepard had a near-impossible task: condense 150 years of history into a 200-ish page book.

“How do you tell the story of how the institution itself helped shape and interpret the greater history of which it was a part?" he asks. "We’re talking about a span of time that stretches from about the closing of the American frontier all through the great scientific advances in chemistry and physics and, of course, biology.”

On Wednesday, April 20, Shepard, Luce, Coffin, and Schagrin will celebrate the culmination of years of work with a virtual book launch.

The story of the Bell Museum—at its inception, a small, humble, regional national history museum—unfolds alongside the rise of numerous scientific disciplines, which makes its story challenging to tell and compelling to read about.

“And then there’s the whole drama of the museum’s struggle to simply survive as an institution within the University [of Minnesota] itself,” Shepard says. “There was a time when it was doubtful whether it would continue, and this kind of mirror of the whole rise and fall and rise again of the whole discipline of natural history in the country—how do you deal with that?”

Authors divvied up the work, tackling their own chapters and peer reviewing one another’s work, making sure the history and science was correct. And they had to get creative with the structure of the book. Rather than telling the Bell's story in linear fashion, you learn about the individuals who made the museum what it is, the programs that altered its course, and the museum’s greater contributions to science.

You might get a chapter about James Ford Bell, the conservationist and General Mills founder who put up half the cost for the original museum, and shortly after encounter a chapter about frogs.

The result is a “many-layered story,” and be warned: “Anybody picking up this book and thinking it’s going to be a nice picture book will very quickly discover that there is much, much more here,” Shepard says.

OK, don't be too alarmed. The book is beautiful, with full-color pages packed with illustrations and photos, and the way it’s laid out means you don’t have to tackle it all chronologically. “That’s actually kind of the way museums are designed, at least the Bell’s exhibits: You can go in anywhere … and it makes sense,” Shepard says.

And you don't have to get very far to fall for the story. In the first few pages of the book, you'll get some context about its origins: It’s 1872. America is still emerging from the rubble of the Civil War, and a group of plucky Minnesota naturalists were like, "We need a natural history museum."

“The Bell is kind of unique in that way, because it was an academic rather than a politician that wrote the legislation that created it,” Shepard says. “And that’s something I didn’t know when we started writing this book--I thought I knew this place.”

“If nothing else, when people read this ... I think they can come to understand what a wonderful treasure this is for the state and for the country," he adds. "It’s just a gem.”