A few years back, my wife Sue, my daughter/fellow Racket contributor Kaylee, and I were geocaching in the small Iron Range town of Mountain Iron when we stumbled on a giant statue in front of the public library. It didn’t have a geocache, which surprised us because they’re usually found on these types of landmarks to help hunters learn something about what they’re looking at—which, in this case, was a sculpture of an old dude sporting a wicked mustache and a pickaxe.

The plaque reads: “Leonidas Merritt, 1844-1926, Pioneer Prospector, Number One of the Seven Iron Men.” That’s it. Being curious artists ourselves, we wondered about this mysterious statue. Who created it? Why did they create it? Who paid for it? We attempted a little research (aka the Duluth Public Library) and quickly learned it was part of the WPA.

Now, when you hear those letters, you probably think of old buildings or roads in your town that were constructed by out-of-work Americans as part of FDR’s New Deal program, the Works Progress Administration. But there was a lesser-known WPA program called the Federal Art Project. From 1935 to 1943, the FAP paid unemployed artists to create murals, paintings, and sculptures in some of those same towns… like Mountain Iron.

It turns out our entire state has some amazing stories from that time period, including the time a Minnesota sculptor had to work in front of an audience at the Walker Art Center while not wearing pants, and we decided it’s high time to get back to that.

Well, not the pants thing, but revisiting those stories, so (momentarily) uninformed folks like you can appreciate not just your WPA-produced neighborhood post office or school, but the artwork that often accompanied them. So, let’s gather round some taconite and revisit some Minnesota stories about that Heck of a New Deal program, the Federal Art Project.

A Pantsless Sculptor From Duluth

Duluth-born Evelyn Raymond is one of Minnesota’s most renowned sculptors; one of her statues even resides in the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C. Every summer, her father took the family with him out into the woods of northern Minnesota, where he worked as a supervisor for a road building crew. Since they had to travel light, Raymond learned to be resourceful, making toys out of twigs and imagination. That creativity came in handy when she was hired by the Federal Art Project to create a bas-relief sculpture for a WPA-funded sports stadium in International Falls.

State bureaucrats decided to show Minnesotans where their tax dollars were going and had Raymond create the three mammoth molds needed for the project out in the lobby of the Walker Art Center. In front of hundreds of people. On a ladder. In a skirt. Evelyn just sewed herself up some pants and finished the job. Of course, she then had to oversee the installation 300 miles away. In International Falls. In January. But that’s Heck of a New Deal story for another day.

Ely’s Double-Muraled Post Office

One offshoot of the WPA Federal Art Project was run by the Treasury Department. The Section of Fine Arts (creatively shortened to The Section) funded artwork for new federal buildings. It also only hired professional artists who submitted bids for the work, as opposed to the Federal Art Project, which wanted to employ as many artists as possible.

Elsa Jemne was one of those professionals. A muralist from St. Paul, Jemne was hired to paint two separate murals for the brand-new Ely post office. Because she was a perfectionist, she went down a clattering elevator with dust-covered, grimy miners 1,000 feet under the earth’s surface into the Pioneer Mine to “get the colors right.” Jemne spent the summers of 1939 and 1940 painting the two murals, entitled “Wilderness” and “Iron Ore Mine.” Interestingly, Postmaster General Norman Brown went missing during Elsa’s first week in Ely, a mystery which remains unsolved.

Although today’s post office employees don’t know about Brown, they can tell you allllll about Elsa and those murals, enthusiastically shoving handouts at patrons who even glance at the murals, which is easy to do. Because Jemne used the “fresco” technique, applying pigments to fresh plaster, the murals are spectacular, looking like they were painted just last week and not 80+ years ago.

A City Nowhere Near Lake Superior Gets a Lake Superior Mural

Not all Section muralists were as connected to their towns as Elsa Jemne and Ely. In 1935, Minneapolis artist Dewey Albinson was hired by The Section to paint a mural for the Cloquet Post Office. A year and a half later, Dewey sent a letter back to the Treasury Department, along with a rough sketch for his mural “Lake Superior Shores-Yesterday and Today.” He was sure it would “appeal to Cloquet” because they are very “fond” of the North Shore, even though Cloquet is a lumber town situated 21 miles away from Lake Superior.

The mural, unveiled in 1937, disappeared sometime in the mid-’60s. No one in Cloquet is 100% sure what happened to “Lake Superior Shores,” but they also haven’t lost any sleep over it, yesterday or today.

A Tale of an Unloved Statue

The Chisholm Class of 1918 applied for Federal Art Project funds for a statue that would encourage future students in the development of their talents and ambitions through the opportunities that the Chisholm schools provided them. “Fountain of Youth” by Samuel Sabean, elegant and beautiful when it was unveiled, today looks like this.

Uff da. The current school administration, staff, and students have no idea what their statue is all about, and don’t really seem to care. However, in 2004, some Hibbing students cared enough to pop the head off and steal it as part of a homecoming prank. Probably not the ambitious talent the Class of 1918 had in mind.

The Story That Started it All: Clement Haupers

Clement Haupers was a Minnesota artist and educator who became the director of the Minnesota division of the Federal Art Project in 1935. He was also the Fine Arts Superintendent for the Minnesota State Fair from 1931-1942, where he discovered a young, self-taught African American sculptor named Robert Crump.

Crump was talented and worked fast, two qualities Haupers needed when he agreed to connect the Iron Range town of Mountain Iron with an artist to create a statue of the town’s founder, Leonidas Merritt for their Golden Jubilee in 1940. Unfortunately, the original artist hired by Haupers hemmed and hawed for months, and when he finally did cough up a design four weeks out from the deadline, town officials hated it. Haupers then did something he rarely did: He fired that artist and turned to Crump.

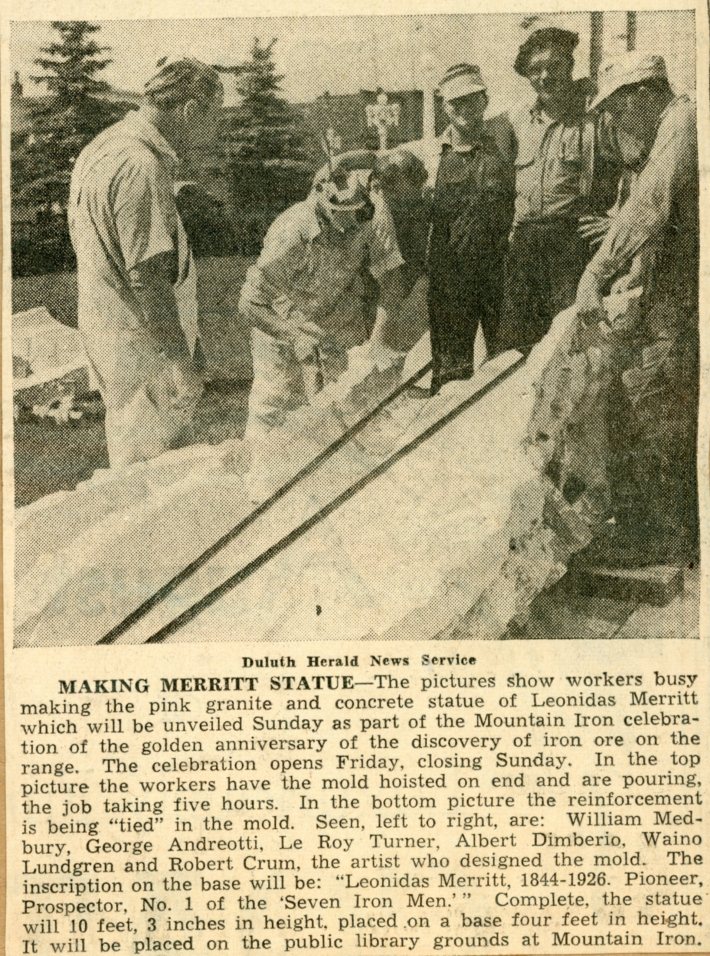

Smart move. Crump got it designed, installed, and unveiled right on time. If Haupers had any qualms about sending an African American artist to the racially tense Iron Range of 1940, he didn’t show it. In fact, a photo from the Duluth Herald shows that the residents working right alongside Crump (or “Crum” as he is misidentified) getting their statue put in place in front of the Mountain Iron Public Library, where it still stands, 85 years later.

Still without a geocache.

Save the Eveleth Mural!

Franklin Elementary School in Eveleth had a huge children’s mural painted in the cafeteria in 1937. The designer, Daphne Haig, was too afraid to go up on the scaffolding to actually paint it, so a younger artist named Elaine Dill scurried up and did it.

Over the years, generations of Eveleth kids grew up playing I Spy with the colorful fairy tale characters depicted in the mural. That connection spurred the Eveleth Heritage Society to try and save the mural after Franklin Elementary was slated for that ever-constant wrecking ball visit.

Statue = Sculpture?

According to the Big Book of Accomplishments, put out by the Minnesota Art Project in 1940 to justify those expenditures to purse-clutching Republicans (sound familiar?), the Grand Rapids Library had a sculpture. Remembering the statue in front of the Mountain Iron library, this “researcher” went “researching” and found... nothing. No one seemed to know anything about it.

Then this “researcher’s” art-knowledgeable wife reminded him that statue is not synonymous with sculpture. Bingo, Big Book! It was another bas-relief sculpture that surrounded the façade of the old Grand Rapids Carnegie library. Fortunately, the building still exists! Unfortunately, it was remodeled in the 1970s and today looks like the photo above. There may be bas relief sculptures under there… somewhere.

A Bovey Mystery

According to the Big Book of Accomplishments, the Iron Range city of Bovey is supposed to have a FAP-funded mural, but we can’t find it. People that grew up in Bovey say it doesn’t exist. People that work in the Town Hall (ironically, built by the WPA) say it doesn’t exist. But the Book says it does! All we can figure is that A) someone saw the mural when it was done, hated it, and immediately painted over it, swearing everyone in Bovey to secrecy, or B) it’s a paperwork snafu by the federal government.

Probably B.