Today, Minnesota is a "poster child" for girls' sports, with some of the highest high school athletics participation rates in the country. But in 1972, there were few options for young women who wanted to play high school sports. Almost no high schools had women's teams; no men's team would let the girls take the field with them.

That's when Peggy Brenden, a senior who played tennis, and Toni St. Pierre, a junior who ran cross country and skied, decided they'd have to take matters into their own hands. They would go through the federal court.

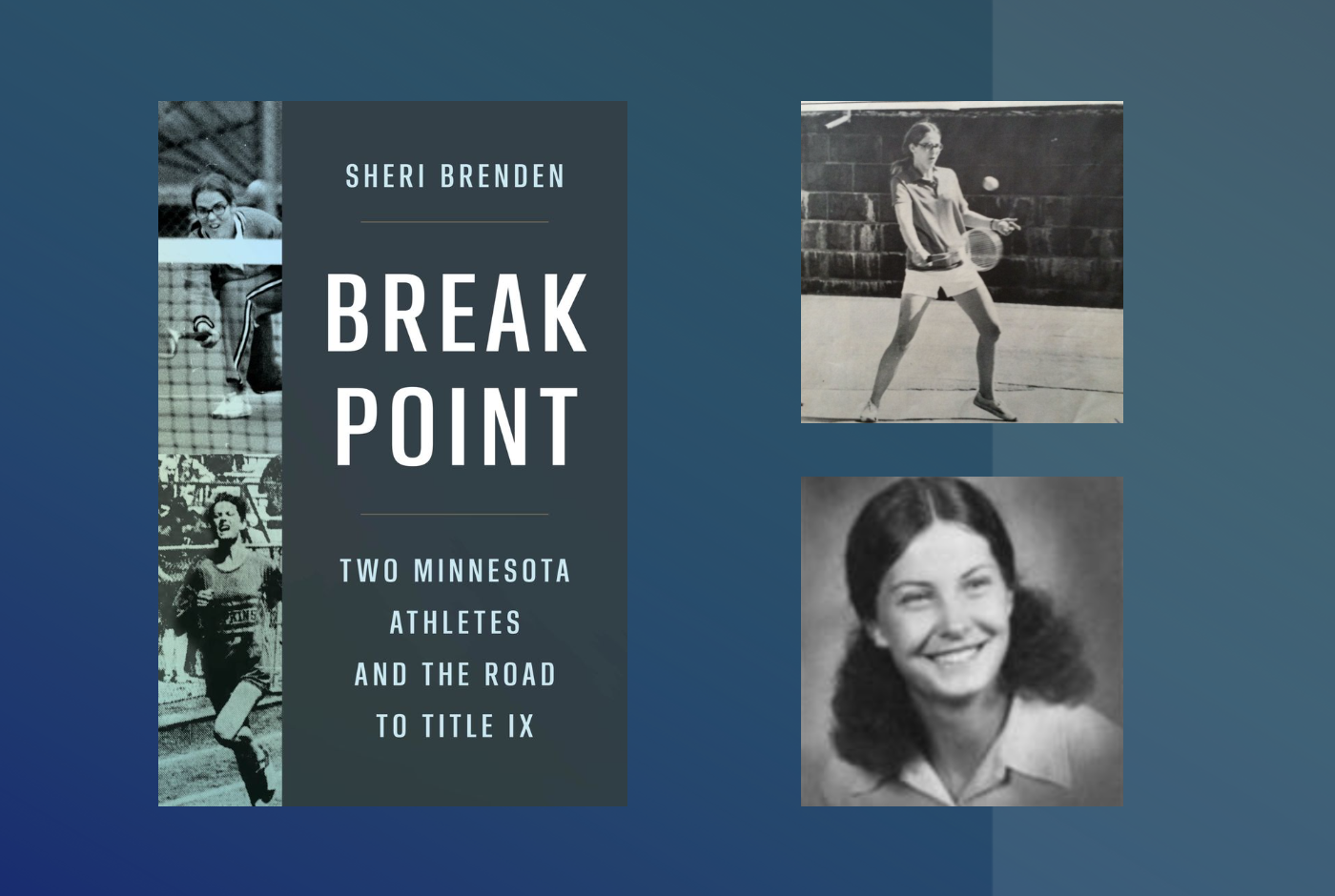

Their story is the subject of a new book by Sheri Brenden (Peggy's sister) called Break Point: Two Minnesota Athletes and the Road to Title IX. Set during the high schoolers' fight, just before Title IX banned sex-based discrimination in schools that receive federal funding, the thoroughly researched (and often heartbreaking) text from the University of Minnesota Press shows how far we've come over the last 50 years with regards to women in sports, and how far we have yet to go.

Before their book launch (January 24 at 6 p.m.; more info here), we sat down with the Brenden sisters to talk about their landmark case, the importance of women's sports, and the things that could still stand to change here in 2023.

Racket: OK, so the year is 1972—not so long ago, but times were very different. Tell me a little bit about your experience during those years.

Peggy: When I was a senior in high school, there were no girls' sports teams at all in my high school, and that was pretty much true across the state. The prospect of playing, it just wasn't on my radar. You talk about "see one to be one"—there was no seeing. The thought was planted the year before, when my older sister and her boyfriend at the time suggested, "You know, you might want to write the Minnesota Civil Liberties Union and see if they'd help you earn a place on your school tennis team." I sat on that idea for my junior year—I did go to the coach and ask if I could play on the team, and he told me, "Sorry, you can't, theres a high school league rule that forbids girls from playing on boys' teams, and if you played we would be disqualified from competition."

By the time the fall of my senior year rolled around, I decided I would follow up on the action that my sister and brother in law had suggested, and I wrote a letter to the St. Cloud branch of the ACLU, and outlined my situation, and told them I wanted to play, that I knew I wasn't the only girl in this situation, and could they help me? I signed the letter, and put it in the mail with a P.S. that said: "Please hurry."

And it sounds like, incredibly, they actually did hurry!

Peggy: Oh my gosh, it was a rocket docket. You do not see cases get on court calendars, particularly in the federal court, with that speed. It was amazing.

Did you anticipate that your case would take off like that? And that you'd soon be thrust into the national spotlight?

Peggy: I didn't appreciate at the time what a big deal it would be. Only as time unfolded, and I looked back in hindsight, did it really hit home the difference that it made.

Sheri: The other thing I would add is, it was 1972, and girls and women had a very different set of options. There were very clear restrictions about what they could become, and what they should do. For example, when I was in junior high, I was required to take home economics—I couldn't choose to take shop. I had to sew an apron; I wouldn't make a birdhouse. As girls were looking to go into college, there were quotas as to how many girls they would allow to enter, and the number of women getting degrees and advanced degrees was sharply limited compared to men. There was just a general tracking going on for girls and women versus boys and men as they pursued their education. It preceded Title IX, which was the law that prohibited sex or gender discrimination in federally funded education.

Right, it's not even limited to sports, just across the board—there is less that you will be able to do. Peg, as you were going into this, did you think that the law was going to be on your side?

Peggy: Well, there was no doubt in my mind that I could participate with these boys and hold my own. That was not an issue. And I had no doubts about the rightness of the position that I was taking. But how it would be handled by the court... that was up in the air, as far as I was concerned. It seemed to me that the right thing to do would be to let us play. But whether the right thing would prevail remained to be seen.

Sheri: There had been other girls challenging this idea in other states, and there was a case in Connecticut where a high school girl wanted to be a part of her track team. The judge didn't base his decision on the law, he really based it on the fact that he didn't think it was appropriate for girls to be competing with boys. He really didn't want to instill those values in young girls, just because we thought it was good for young boys.

What made you think that this story, which unfolded 50 years ago, was something that was relevant today?

Sheri: I lived through this with my sister, and I was kind of conscious as the years went on that it had a bigger impact than other people seemed to recognize. I'm also going to say that I'm pretty tired of always reading about the male greats of athletic history. I've seen these stories about high school sports history, and they're always male. I thought, "This is more important, this is more interesting. Why is the world overlooking my sister's story?"

As I started to look into it, I started to appreciate that it wasn't just my sister's story, it really was a story for all girls and women. The opportunity that opened up to us—high school sports is huge, not just in terms of school, but how it grows leadership capabilities and female networks and interpersonal skills and confidence about your capabilities and your body. I thought: This story needs to be told. And I was the one to tell it, because I was her sister, I was an athlete, and I was a woman who knew what this meant.

You're absolutely right about that. I was a three-sport athlete all through middle and high school, and I can't tell you how much that built my confidence, and how much it shaped the person I am today.

Sheri: And I think, now that it's become so common, we start to forget that it's still an institution that was built with boys and men in mind, and it's still dominated by boys and men. We don't see the corresponding growth, yet, in women in coaching, in women in athletic directorships, women in sportswriting, women commentators—all the things that are part of the sports industry. Because we still aren't gaining the respect for our stories and our capabilities.