An urban legend persists in many American cities that their once-robust public transit systems were destroyed by some kind of conspiracy, whether it's the auto industry or other crooked industrialists in cahoots with city leaders.

“But it’s only in the Twin Cities that the conspiracy was real,” chuckles Jake Berman, author of The Lost Subways of North America: A Cartographic Guide to the Past, Present, and What Might Have Been (University of Chicago Press, 272 pages).

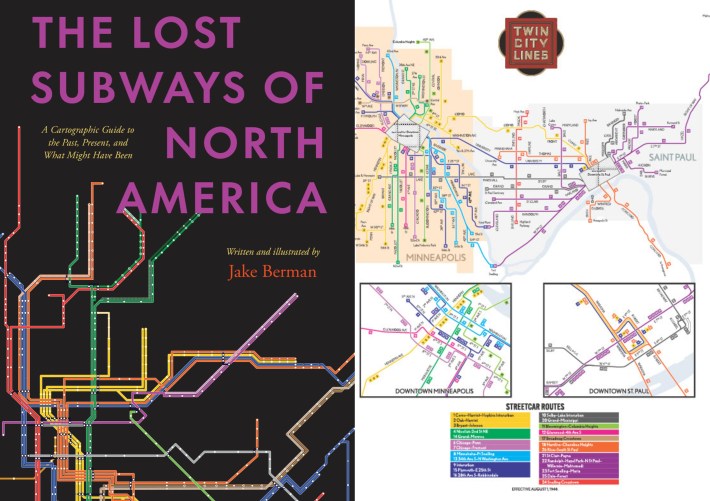

In Lost Subways, published last month, Berman explores the transit history of 23 cities in the U.S. and Canada, from New York City’s Civil War-era dreams of a steam-powered subway to L.A.’s pre-WWII electric railway system. And the story in Minneapolis and St. Paul? “Well, it's quite eye-popping,” Berman says.

You see, the Twin City Rapid Transit Company streetcar system that once snaked through the greater metro didn't just fade away as buses and automobiles became de rigueur. Instead, it met its untimely demise thanks to a greedy Wall Street investor—and the Minneapolis mob.

The streetcar’s rise and fall begins with Thomas Lowry. Yes, that Thomas Lowry. “Anything named after Lowry is named after the original owner of Twin City Rapid Transit—so you know, Lowry Hill, Lowry Avenue, and so forth,” Berman explains. As the head of Twin City Rapid Transit Company, which formed in the 1886 merger of the Minneapolis Street Railway and St. Paul City Railway, the businessman and real estate mogul oversaw the early growth of the Twin Cities’ streetcar lines.

Lowry died in 1909, but TCRT would remain in the family until after World War II. That's when it passes to D.J. Strouse, a manager at the company.

“Strouse was the president of the company in the 1940s,” Berman says. “And he made major investments in fixing the streetcar system, which had been heavily used during the Great Depression and the second world war.”

Strause has a vision of modernizing the streetcar system, replacing lesser-used lines with buses while investing in the busiest routes with new cars and equipment. “This was a guy who’s thinking… ‘Streetcars are more comfortable, they have higher capacity than buses, and we’re going to upgrade the routes that are busiest and keep them in streetcar operation,’” Berman continues.

Unfortunately, that decision ultimately would lead to the end of the Twin Cities’ streetcar system. Strouse spends a lot of TCRT profits in order to make the modernizations he wants to see. And, TCRT being a publicly traded company, this doesn’t make Wall Street investors terribly happy. “In particular, there was a fellow named Charles Green who bought a bunch of companies’ stock and expected a huge dividend out of it,” Berman says.

Green is so upset, in fact, that he starts a hostile takeover attempt, one for which he approaches another of TCRT’s major shareholders: Isadore Blumenfield, also known as Kid Cann—also known as the godfather of the Minneapolis mob.

Now, Kid Cann is more or less untouchable. If you’re familiar with the gunning-down of Pulitzer-winning newspaper editor Walter Liggett, it’s Cann who ordered the assassination (and got away with it). “He gets indicted in Oklahoma for money laundering—by the feds, no less—and the police chief of Minneapolis goes down to Oklahoma and testifies on Kid Cann’s behalf,” Berman says. Not a guy you want to cross.

Green and Cann loop in Fred Ossanna, a St. Paul political fixer for the freshly merged Minnesota Democratic–Farmer–Labor Party. A criminal lawyer, Ossanna had become quite wealthy representing the liquor industry’s interests at the State House. “And guess who has a big amount of control of the liquor industry in 1948?” Berman muses hypothetically. Why, none other than Kid Cann, a former bootlegger who now controls the Twin Cities’ legal liquor trade.

Stop us if you’ve heard this one before: A finance bro, a gangster, and a crooked lawyer walk into a bar… Cann, Green, and Ossanna make a plan to oust Strouse and organize a letter-writing campaign to TCRT’s shareholders. Their plot works. In ’49, the shareholders force out Strouse, and Ossanna becomes chief council of the transit company. Charlie Green is installed as president.

But Green’s NYC swagger doesn’t work so well here in the Midwest. When he gets in front of the cameras and threatens to sell off the buses and trains for scrap iron to make the company profitable, quickly cutting service and firing 800 workers, people don’t like it.

“This is aggressive, New York City dickhead moves that do not play well in Minnesota,” Berman says. “At the same time he’s going to the state railway commission asking for a fare hike, he’s also slashing service left and right.”

Green quickly wears out his welcome with his co-conspirators, and he’s ousted within six months. He’s forced to sell his shares, and Cann is only too happy to buy them up. And thus, the real dismantling of the streetcar system begins. Cann and Ossanna sell off the trains even faster than Green had, getting kickbacks from the purchasers for their bargain basement prices.

This infamous photo from 1954 of TCRT treasurer James Towey handing Ossanna a check as the streetcars burn is almost too sinister-looking to believe.

“They sell off everything, they close the entire streetcar system, and transit ridership drops like a brick,” Berman says. According to his book, these sneaky dealings defrauded Twin City Rapid Transit out of about $1 million (or roughly $10 million in 2023 dollars).

“By ’54, the Twin Cities have no more streetcar system,” he continues. “It’s all buses.”

In 1959, the feds find out about this deal, and they arrest Cann and Ossanna on fraud and conspiracy charges. Ossanna gets indicted, stripped of his law license, and thrown in prison. The ever-slippery Kid Cann beats the charges—but he’s arrested again not long after for transporting a prostitute across state lines.

“And they nail him,” Berman says. “It was really really hard to nail him on fraud, racketeering, murder—whatever rackets he had run for 20 or 30 years of being a big-shot gangster. But it was actually easy to prove that he had transported a prostitute from Chicago to Minneapolis.”

The destruction of the streetcar system is long over, of course. By the time Ossanna and Cann face any consequences, mass transit has all but entirely faded away in favor of the automobile. Not until the early 2000s would the Metropolitan Council’s light rail lines open, running parallel to the old Twin City Rapid Transit lines.

Of course, the streetcar systems in most major American cities eventually disappeared. So did Kid Cann and Frank Ossanna hasten the system’s inevitable demise in Minneapolis and St. Paul? Or does Berman think there’s a chance we might still have a streetcar system today without these dealings?

Berman concedes that the North American cities where streetcars persisted tend to be those where there were technological limitations—San Francisco, Philadelphia, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh—places with narrow, tight areas like trenches or tunnels that couldn’t be used as a busway.

There are exceptions to the rule, though. Toronto bought up the old streetcar trains everyone else was getting rid of for next to nothing, and still has 11 streetcar routes today. In New Orleans the St. Charles Avenue streetcar line, today a symbol of the city’s enduring charm, was saved by urban aesthetes who wanted to preserve the boulebard’s palm trees and grassy median in favor of buses.

So maybe there’s a version of this story that could have ended with TCRT enduring.

“In the late 1940s, DJ Strouse, the original company president, had the correct idea,” Berman says, “which is: Upgrade the busiest lines, shut down less-busy lines, and modernize them to bring them into the 20th century, so to speak.”

The state-of-the-art street cars the company purchased under Strouse? They were so well built that some are still in service in San Francisco three quarters of a century later.

“I think there was a reasonable chance of the old streetcar network becoming the basis of a modern light rail network, given the reforms that the old management was making,” Berman adds. “But we never got to see the way that turned out because of the mob, and a finance bro, and a crooked lawyer.”