The Lost and Forgotten Waterfalls of the Twin Cities

Meet the falls that eventually became parking lots and warehouses, and learn about the lesser-traveled ones that are diminished, but still remain.

12:41 PM CDT on September 12, 2022

Silver Cascade in 1865

This story originally appeared on The Minnesota Historian, a new local history website from Josh Biber.

There once were over a dozen cascading falls along the banks of the Mississippi River Gorge, a deep channel that cuts into the bedrock between Minneapolis and St. Paul to the south of St. Anthony Falls. Hundreds of springs can still be found on either bank, and while most of them are just small fissures of water trickling through the limestone walls, a handful once emerged as magnificent waterfalls. However, the advent of settlement, industrialization, and development of sewage systems in the area at the turn of the 19th century have greatly impacted the watershed of these small but plentiful streams. Today, the waterfalls have mostly vanished.

Around 10,000 years ago, before these tributary waterfalls came into existence, the Mississippi was a much larger river; it flowed in two courses around a rocky island where the Minnesota Veterans Home now stands. Just downstream from this ancient island, the precursor to St. Anthony Falls was slowly eating away at the riverbed as it worked its way upstream. As the Mississippi spilled over the edge of the falls, the water washed away the sandstone bed underneath. The undermined and weakened limestone collapsed, allowing St. Anthony Falls to inch its way further upstream ever so slowly. When St. Anthony Falls reached the southern edge of the knobby island where the Veterans Home now stands, the waterfall divided into two separate falls. Each of these falls wore down the riverbed on either side of the island.

The eastern falls had the advantage because it had a short, straight channel to consume, slowly working upstream to form the present-day river gorge and St. Anthony Falls. The western falls heaved and eroded furiously around a bend in the island, eventually joining with the mouth of Minnehaha Creek. Minnehaha Falls was born. Today, there's no island beneath the Minnesota Veterans Home. Rather, this slice of land is now a peninsula straddled by Minnehaha Creek to the west and the Mississippi to the east. As the deep Mississippi River Gorge formed, surrounding springs and streams naturally flowed towards the low lying river, creating many magnificent waterfalls.

There are several waterfalls both present and lost within Minnesota’s two largest cities. The closer you look, the more you just might find—water like silver strands plunging into the grottos below. Let's dive into these waterfalls, where they’re located, and their histories.

The Cascades of Minneapolis

Chalybeate Springs

These springs once flowed from a rocky overhang underneath the bluffs on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River, just below the Pillsbury A-Mill. Chalybeate Springs was a collection of five small spring-fed falls that erupted from the Glenwood Shale cliff face. Known as “the elixir of life,” its waters were noted for being refreshingly cool and clean with a mineral taste. The springs were also thought to have medicinal properties that could cure many ailments. These springs were heavily sought after by surrounding residents who often filled tanks of the spring water for their homes.

In the 1870s, Chalybeate Springs became a popular congregating place for citizens of all classes and creeds. Local musicians would frequently serenade residents as they lined up in droves to get their fill of the reportedly medicinal waters. A copper sundial was also placed near the springs; on any given day it wasn’t uncommon to find several individuals calibrating their watches at the dial. The springs also attracted young deviants who would catcall women and rile up men. When the copper sundial was stolen in 1880, the city posted a police officer at the springs while the local newspapers sternly warned, “unless the rowdyism is ended before long, a description of the scamps will appear in these columns as a guide for the public to go by.”

In the 1880s, an entrepreneurial citizen began chartering regular boat trips on the Mississippi underneath the rocky outcropping at the springs. For more adventurous tourists, the guide paddled his boat up the Chute Tunnel, a 900-foot-long man-made tunnel created in 1864 in an attempt to provide a canal to power the mills on the east bank. The Chute Tunnel opened up to a collection of natural limestone caves beneath the Pillsbury A-Mill complex. This trip—featuring the gurgling springs, the spreading elms, the shady nooks, the view of St. Anthony Falls, the Chute Tunnel, and the roar of the mighty Mississippi as it rushed past—was once a popular, romantic, and daring tourist attraction.

Because of the rumors of Chalybeate Springs’ medicinal properties, plans were once underway to create a company that would bottle and ship these healing waters to communities throughout the country. However, just before the bottling operation began, word spread that the spring water didn't in fact have any medicinal or healing properties. In reality, the water was quickly becoming polluted by runoff from the mills on the bluffs above. Plans for the bottling company were quickly scrapped, and Chalybeate Springs lost both its popularity and its miraculous healing powers. In 1885, the springs and the surrounding land were sold to industrial ventures. Over the last 140 years, Chalybeate Springs have passed obscurely into history.

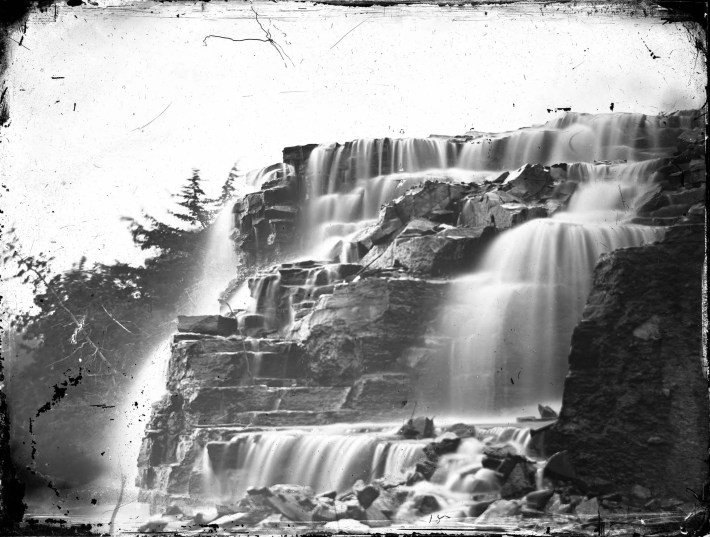

The Three Sisters: Fawn’s Leap, Silver Cascade, and Bridal Veil Falls

In a span of about a mile-and-a-half there once were three waterfalls that plunged over the cliffs of the Mississippi River Gorge’s east bank. From north to south, these falls were Fawn’s Leap, Silver Cascade, and Bridal Veil Falls. Of the three falls, only Bridal Veil remains—though in a much diminished state compared to its former glory.

An 1888 editorial in The Minneapolis Tribune advocated for turning this area into a park to be named Riverside Park. The anonymous writer suggested: “A city park should be located where nature has provided the hills, the valleys, the precipices, the running water, the water falls, and all the variety of scenery. There is just such a place at our very doors. Bridge the river where it is intersected by Washington Avenue continued and you are landed in a region that is at once picturesque and possessed of unlimited capabilities. Let anyone follow down the river bank and he will be struck with the great advantages of this locality for a park.”

Of these three waterfalls, the first sister was Fawn’s Leap. The location of Fawn’s Leap was roughly adjacent to the present location of the I-35W bridge in the Marcy Holmes neighborhood. Fawn’s Leap was a nearby reprise from the hustle and bustle of the early years of industrialization in St. Anthony and Minneapolis.

Fawn’s Leap was fed by a small surface stream that rose from marshland in the then-sparsely populated area on the outskirts of St. Anthony. As the small tributary traveled downstream toward its mouth at the Mississippi River, its small muddy banks gave way to a 30-foot cataract that emerged out of the limestone face on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River Gorge. Rightly named Fawn’s Leap, the gully of the falls was once teeming with wildlife and a plethora of flora. But Fawn’s Leap met its demise by the hands of industrialization when the Stone Arch Bridge was completed in 1883. These falls stood in the way of railroad tycoon James J. Hill’s plans to construct a railroad depot for his Great Northern Railway Co. near the intersections of Hennepin and Nicollet Avenues. The encroachment of the Great Northern Railway tracks on the eastern bank of the Mississippi all but decimated Fawn’s Leap. The railroad cut off Fawn’s Leap from its source, thus, the waterfall displayed its former glory only after large rainfalls. As time progressed, the waterfall and its grotto were leveled for the development of warehouses. This waterfall has mostly been lost to history, with its last reference being in a 1935 article.

The second sister was colloquially known as Silver Cascade. Silver Cascade was a short jog to the south of Fawn’s Leap, near the present-day location of the heating plant on the University of Minnesota’s East Bank. Silver Cascade was fed by Tuttle’s Creek, which originated in the marshes of the Como neighborhood. This was a small brook that flowed southwest from the Como neighborhood into the Dinkytown before discharging into the Mississippi River. The former headwaters of Tuttle’s Creek are near the aptly named SE Brook Avenue in Como.

Silver Cascade was a beautiful waterfall, as you can see. Protruding from the falls were a collection of large, rocky drops where the water lazily plunged over to create an assembly of several small cascades. This waterfall was popularly photographed in winter due to its magnificent ice formations. However idyllic Silver Cascade once was, this waterfall too stood in the way of Minneapolis’s industrialized surge during the late 1800s.

The first intrusion of industry at Silver Cascade and Tuttle’s Creek occurred In the 1870s as a wholesale pickle factory opened immediately to the north of the U of M, diverting Tuttle’s Creek as a source for water power. Much like Fawn’s Leap, Silver Cascade was nixed by the construction of the Great Northern Railway, which separated the waterfall from its natural water source in 1883. The rest of Tuttle’s Creek was subjected to a sewage drain that ran underneath the university. Part of the former creek is displayed in the 1898 city atlas, but by the 1903 atlas, the creek is no more.

The third sister of this trio of waterfalls was Bridal Veil Falls. Once a trysting place for couples looking for a romantic getaway, Bridal Veil Falls was an impressive waterfall with its waters emptying into a wild ravine that flowed into the Mississippi. Bridal Veil Falls exists today with none of its former glory. Over the last century-plus, the very existence of Bridal Veil Falls has come into contention many times.

Just to the north of the railroad tracks opposite Surly Brewery lies the former headwaters of Bridal Veil Creek, once rising from swamps and ponds straddling the border of Minneapolis and St. Paul. As this area gave way to industry and the development of the St. Anthony Park, Como, and Prospect Park neighborhoods during the early 1900s, the creek was buried into a culvert underneath city streets. What remains of Bridal Veil's headwaters are now a collection of isolated eutrophic storm retention ponds.

In 1909, plans were made to fill the Bridal Veil Creek bed in its entirety, thus diverting the outflow of water into nearby storm drains. This suggestion came after the Minneapolis Park Board Superintendent, Theodore Wirth, examined Bridal Veil Creek during that summer. Wirth reported that the creek, which once had a modest watershed area that formerly made Bridal Veil Falls famous, had become a vile and polluted stream.

“At present a very small amount of water is running in the creek channel," Wirth lamented. "The territory through which the creek runs is rapidly building up with [grain] elevators, warehouses, factories and railroad yards and has been used for a dumping ground for so many industries that the water is now a menace to the public health.”

Wirth’s observations were met with pushback. The St. Anthony City Improvement Association consulted with the Park Board to discuss any possibilities of cleaning and restoring Bridal Veil Creek and avoiding subjecting the creek into a de facto sewage drain.

Despite efforts to preserve the creek, Wirth’s vision for the area prevailed. During the early 1900s, Bridal Veil Creek was entombed into a drainage system underneath railroads, factories, and homes. Today, Bridal Veil Falls now emerges from a drain pipe underneath East River Parkway, north of the Franklin Avenue Bridge. Here, the sickly falls dutifully trickles to the river below, without any of the former magnificence or splendor that they were once revered for.

In the early 1950s, Bridal Veil Falls's existence came into contention again when much of the water flowing into the culvert was joined by a new connection to the city’s storm sewer system. The little water that flowed from the mouth of the culvert at Bridal Veil Falls was now joined with wastewater from the surrounding industrial facilities. The falls became mired with a slurry of chemicals and effluent waste.

Complications only continued at Bridal Veil Falls with the encroachment of I-94 during the mid-to-late 1950s. I-94 was dug into a 16-foot deep trench so it could underpass East River Parkway, 27th Avenue SE, and Franklin Avenue without disrupting the flow of traffic. (The interstate would infamously disrupt the historically Black Rondo neighborhood of St. Paul.) The new path of I-94 was at a lower elevation than the precipice of Bridal Veil Falls. In an effort to conserve the falls, engineers had to construct a new drainage culvert several feet below the previous culvert's precipice to keep some water flowing into the falls. Luckily, the engineers corrected the storm sewer system and redirected the wastewater runoff to a wastewater treatment facility in St. Paul.

Today, Bridal Veil Falls is an urban explorer’s paradise, conveniently tucked away beneath East River Parkway and out of sight from peering onlookers. In the winter, the falls are particularly popular among ice climbers. Here, you can find graffiti covering the mouth of the falls and a retaining wall that supports the parkway. If you plan to visit, I suggest bringing a trash bag and gloves to clean up the detritus and waste from the storm sewer runoff.

Hajduk Springs

Once described in the Minneapolis Tribune as the ultimate cure for hangovers, a small hidden waterfall among the hustle and bustle of Minneapolis—Hajduk Springs—can be found in a grotto along the bluff side below the intersection of East 24th Street and West River Road.

Hajduk Springs were originally discovered by Seward resident Harry Hajduk in 1971. Hajduk popularized the spring, boasting that the clean mineral water was better tasting and purer than the city’s tap water. Hajduk reported the spring to the Minneapolis Park Board, who tested the water purity and confirmed that the spring was 100% pure. After the Park Board informed Hajduk that the spring had a clean bill of health, Hajduk next worked with the Center of Community Action to build steps and a trail down to Hajduk Springs.

The small trail spur to Hajduk Springs was used to connect to the Winchell Trail, but the spur has since fallen into disrepair. To the adventurers who would like to rediscover Hajduk Spring, first head along the limestone cliff face near the Winchell Trail. If you are traveling in the right direction, the first hint of Hajduk Springs will be the gurgling sounds of water. Carefully follow the sound of the rushing water and soon you’ll find an outcrop of stone and see the spring.

Hajduk spring gushes from a limestone crack roughly 20 feet above at about 15 gallons per minute. The spring falls into a mossy bed below, joining with a tumbling brook that connects with the Mississippi River. Be warned: This is not an easy hike—especially if you're nursing a hangover.

Atwater Falls

I could only find one historical reference for Atwater Falls, in a 1935 article from The Minneapolis Journal. In this article, a reporter interviewed S. S. Johnson, an early settler who came to Minneapolis as a boy in 1860. The Johnsons lived at 1312 8th St. S. in an old neighborhood of Minneapolis called the Atwater Addition. This slice of Minneapolis, just southeast of downtown, was said to contain a small marshland located where the present interchange of I-94, I-35W, and Hwy. 55 meet. Johnson recollected that out from this marsh once “ran a beautiful winding creek that made its way diagonally to the river, into which it plunged over the picturesque Atwater Falls.”

The Atwater Addition neighborhood, the marsh, and the falls have since been lost to development. When reviewing Johnson’s memory and claims of the falls location, as well as surveying a few old maps, my estimate is that the Atwater Falls exited into the Mississippi River Gorge somewhere on the bluffs above the Annie Young Meadow. Today, there is a small trickle of water that creeps over the limestone retaining wall and shale cliff face adjacent to West River Parkway upstream from the meadow. This could just be the remnants of the lost Atwater Falls.

Minne-Boo-Hoo Falls

Much like Atwater Falls, there’s only one reference to the Minne-Boo-Hoo Falls, in a 1901 article. The falls’ name was a play on words, contrasting with the more jovial name of Minnehaha Falls. It’s cited that this waterfall was about three-quarters of a mile north of the Veterans Home, in a deep ravine where the falls sluiced over a 10-foot drop before entering the Mississippi River Gorge. This measurement would put the location of these falls somewhere near the southern end of the Winchell Trail.

My assumption is that the Minne-Boo-Hoo Falls name has been lost to time, but the location of the falls remains as a stormwater culvert, where the former falls now exist as a dry shale face, re-emerging after heavy rainfall. If my assumption is correct, this is a very likely candidate for the lost Minne-Boo-Hoo Falls.

Novelty Falls

Hidden in plain sight in the Minnehaha Dog Park lies Novelty Falls. Novelty Falls is across the Mississippi River from St. Paul’s Hidden Falls. Once a limestone quarry operated by the Minneapolis Park Board in the early 1900s, the area was later turned into Minnehaha Dog Park. There are several remains of the old quarry, namely, a few old kilns and an old incinerator still within the park’s boundaries. Novelty Falls tumbles over a roughly 15-foot sandstone cliff. During the drier season, Novelty Falls runs dry. In the winter and spring, Novelty Falls provides a sizable trickle of snow and rain runoff.

Coldwater Spring (Mni Owe Sni)

Just over a half-mile south of Novelty Falls is Coldwater Spring. Producing over 140,000 gallons of water daily, Coldwater Springs is a historic place in the southeast reaches of Minneapolis. The spring, carved out of St. Peter sandstone near Fort Snelling, flows about two-thirds of a mile before it plunges over a sandstone bluff into a tree-lined backwater of the Mississippi River.

Once a sacred gathering place for the Dakota and other Native Americans, Coldwater Creek Euro-American settlers came upon it in the 1820s. That's around the time Camp Coldwater was erected near the source of the spring at the apex of the bluffs along the Mississippi while Fort Snelling was still being constructed. Camp Coldwater became a cradle of Minnesota heritage, as it was one of the first places where there were regular interactions between the Dakotan people and Euro-American settlers. When Fort Snelling was completed, Camp Coldwater slowly crumbled into memory as years of spring floods covered the location in a deep layer of silt.

Coldwater Spring returned to memory in the late 1990s when the proposed reroute of Hwy. 55 was plotted to put Coldwater Spring and the surrounding heritage sites on the chopping blocks. The paramount concern for many was to preserve the site for its Native American history. However, a secondary concern was that the road project risked interfering with the flow of groundwater to Coldwater Spring and the destruction of a large swath of ancient prairie oak savanna. The Earth First movement occupied a few acres of land at Riverview Road to peacefully protest the Hwy. 55 reroute project.

Hwy. 55 eventually prevailed. However, changes to the original plan were made to protect the flow of the spring. Coldwater has since been painstakingly restored into a prairie oak savanna—one of the few remaining in the U.S.

The Cascades of St. Paul

Kavanagh Falls

Kavanagh Falls were a cascade over several steps of rough limestone ledges named after the former owner of the land these falls were on. Today, the land is the grounds of the Town and Country Club. In an 1891 article, a columnist wrote of Kavanagh Falls: “The plateau falls abruptly away to a picturesque glen or gorge, through which a brook purls to the level of the lawn, and then leaps laughingly to the river below. To make travel in the area easier, a bridge once spanned the Kavanagh Gorge. The spring that once fed the falls remains on the grounds of the Town and Country Club. However, the bridge and gorge that these falls once tumbled into has since been filled to provide additional parking spaces for club members.

As an aside, there was another unnamed waterfall in the close vicinity of Kavanagh Falls. This second falls was to the north, closer to Meeker Island. With the construction of the Lock & Dam downstream at the Ford Bridge, the Mississippi waters rose roughly 15 feet to make this section of the Mississippi easier to navigate. Thus, both Meeker Island and this unnamed waterfall were erased from the landscape.

At some point, the ravine that Kavanagh Falls tumbled into was filled. One researcher, Drew Ross, took to investigating what became of Kavanagh Falls. Ross concludes when the Lake Street-Marshall Avenue Bridge was reconstructed in the late 1960s, Mississippi River Boulevard was reconfigured to run underneath the newly constructed bridge. “As Mississippi River Boulevard was reconfigured, Town and Country saw an opportunity to expand their clubhouse grounds," Ross writes. "They purchased the properties north of the clubhouse, removed one house, and arranged to have the dirt that was removed for the Mississippi River Boulevard/Marshall intersection fill Kavanagh Ravine… They increased their parking, built a new swimming pool, tennis courts, and an outbuilding. This also eliminated the need for a bridge over Kavanagh Ravine.”

Compared to the history of several of the other falls in Minneapolis and St. Paul, the nixing of Kavanagh Falls occurred relatively recently--within the last 55 years. The loss of the falls is another predictable let down by the hands of city planners of the past. The once beautiful falls are now no more than a parking lot for a private country club. What’s more important to you, preserving a natural waterfall and ravine 10,000 years in the making, or improving your short game?

Shadow Falls (Minnesheena)

Kavanagh Falls and the unnamed waterfall mentioned previously were once two of the several small cascading falls along the east bank of the Mississippi river between the Ford Bridge and Meeker Island. However, the advent of settlement and development of sewage systems in the area at the turn of the 19th century have greatly impacted the watershed of these small but plentiful streams. Today, Shadow Falls are the best kept remains of these ex-cascades.

Shadow Falls can be found along East River Parkway near the Summit Avenue intersection. Here, you can find Shadow Falls Park. A small tributary runs through the ravine, where a dearth of water tumbles over a small limestone ledge into a grotto below to form the mysterious waterfall for which the park is named after.

In the late 1890s, suggestions were made to supplement the small stream with a water pump to enhance the falls, however this was not exploited, as the falls are not easily reached and there wouldn’t be much return on investment. Today, Shadow Falls is a popular hiking spot near the St. Thomas campus. It’s best to visit these falls when the autumn colors are in full force.

Hidden Falls

Located just south of the new Highland Bridge development in St. Paul, Hidden Falls has been heavily tampered with and modified during the development of St. Paul.

Originally, the source of Hidden Falls was a spring and natural surface drainage from the Highland Park area. Just like other creeks and waterways in the Twin Cities, the encroachment of development has forced this water system into an underground drainage pipe.

Hidden Falls now emerges from said drainage pipe on a limestone cliffside. If you ignore the drainage pipe, you can focus on the several romantic drops the falls plunge over before meandering through Hidden Falls Park where it joins with the Mississippi River.

Homer's Odyssey / Crosby Farm Falls

Nestled deep within a slot canyon off the beaten path in Crosby Farms Regional Park lies the secretive waters of Homer's Odyssey.

The land was once owned by farmer and St. Paul resident Thomas Crosby, who owned and operated his farm until 1886. This land continued to be used as farmland until the 1960s, when it was bought by the city of St. Paul and turned into a municipal park.

The falls are not marked on any trail, thus they are largely hidden to most passerby. Homer's Odyssey lies within a limestone canyon where the outlet of water finds its way into Lake Crosby.

Ivy Falls

This hidden waterfall is tucked away between neighborhood developments in Mendota Heights (I know, it’s not St. Paul but I couldn’t resist). The falls themselves are a modest trickle of water into a rocky grotto below. In the winter, these falls make for a magnificent icy display. This waterfall is deep in the woods above the Mississippi River just downriver from Bdote. However enticing it may be to discover Ivy Falls for yourself, be warned: They're located on private property and there is no way to access them without trespassing.

Our Picturesque Little Waterfalls

These many waterfalls were once (and, in some cases, still are) places where you could find relief from the city, descending into a world filled with the sounds of rushing water, wind rustling the oak and linden trees, and squirrels chattering in the branches above.

Unfortunately, we've lost many of the original waterfalls of Minneapolis and St. Paul. Chalybeate Springs, Fawn's Leap, Silver Cascade, Atwood Falls, Minne-Boo-Hoo, Kavanagh Falls, the unnamed waterfall, and yet another waterfall that I couldn't find information about called Lilly Giggle Falls have all been lost during the last century-and-a-half.

Next time you find yourself at one of these hidden places, consider picking up the debris of the city--pieces of paper, candy wrappers, cans, and beer bottles--to help in returning these falls to the way nature intended.

Sources:

- Brick, Greg. “Along the Great Wall: Mapping the Springs of the Twin Cities” Minnesota Ground Water Association, Volume 16, Number 1, March, 1997. https://www.mgwa.org/newsletter/mgwa1997-1.pdf

- Rybski, John. “The Cities’ Secret Waterfalls” Minneapolis Tribune, December 1, 1974. P. S1.

- Thornton, Ralph. “Parts of 1819 Military Camp Found” The Minneapolis Star, June 30, 1964. P. 7B.

- “Shadow Falls Drive” The Saint Paul Globe, May 17, 1898. P. 10.

- “Unbelievable Hidden Slot Canyon in St. Paul at Crosby Farm Regional Park” Day Tripper. https://daytripper28.com/minnesota-adventures/hidden-slot-canyon-in-st-paul-at-crosby-farm-regional-park/

- “Cycle-Seen Glory” The Saint Paul Globe, May 10, 1896. P. 16.

- Upham, Daniel. “Road Engineers Find Way to Save Bridal Veil Falls” Minneapolis Tribune, May 28, 1961. P. 9

- “Historic Bridal Veil Falls May be no More” The Minneapolis Tribune, July 30, 1909. P. 6.

- Holmes, Hilary. “Bridal Veil Falls” Open Rivers, 2017.

- “To Our Guests.” The Daily Evening Journal, July 22, 1880. P. 4.

- “Riverside Park” The Minneapolis Tribune, June 4, 1888. P. 9.

- “Minnesota Revealed as Tourist State in Early Days When California was Luring Prospectors” The Minneapolis Tribune, October 8, 1922. P. 8.

- “Rowdyism at the Chalybeate Springs” Minneapolis Tribune, June 5, 1876. P. 4.

- Chin, Richard. “Spring Fever” Star Tribune, March 18, 2018. P. E8.

- Flanagan, Barbara. “It’s Springtime” The Minneapolis Star, August 27, 1974. P. 84.

- Brandt, Steve. “Vision, Sweat Return Spring to its Past” Star Tribune, September 23, 2016. P. OW1.

- “Three More Falling Waters” Nokohaha, January 30, 2016. https://www.nokohaha.com/2016/01/30/three-more-falling-waters/

- “Ever Hunt Ducks at Third and Nicollet? This Man Did” The Minneapolis Journal, March 3, 1935. P. 4.

- Ostmann Jr., Robert. “Minnehaha Falls: History Murmurs in Roar of Waters” The Minneapolis Star, January 16, 1979. P. 1.

- “Swell Town and Country Club” The Saint Paul Globe, June 7, 1891. P. 1.

- Ross, Drew. “Reclaiming Mississippi River Boulevard” StreetsMN, January 10, 2019. https://streets.mn/2019/01/10/reclaiming-mississippi-river-boulevard/

- “Unbelievable Hidden Slot Canyon in St. Paul at Crosby Farm Regional Park”, https://daytripper28.com/minnesota-adventures/hidden-slot-canyon-in-st-paul-at-crosby-farm-regional-park/

- William, Jacoby. "Chalybeate Springs near Pillsbury A Mill, Minneapolis" Minnesota Historical Society, 1875. http://collections.mnhs.org/cms/largerimage?irn=10102980&catirn=10719994&return=count%3D25%26imagesonly%3Dyes%26q%3Dchalybeate%2520springs%26tab%3Dresearch_items

- "Pillsbury A Mill Water Power Tunnel (1882) Minneapolis, Minnesota" Arch3, LLC, 1882. http://arch3llc.com/pillsbury-a-mill-headrace-tunnel-1882/

- "Fawn's Leap Falls, Minneapolis" Minnesota Historical Society, 1875. http://collections.mnhs.org/cms/display?irn=10825078&return=count%3D25%26imagesonly%3Dyes%26q%3Dfawn%2527s%2520leap%26tab%3Dresearch_items

- "Silver Cascade in 1865" Hennepin County Digital Library, 1865. https://digitalcollections.hclib.org/digital/collection/p17208coll18/id/420/rec/11

- Illingworth, William. "Silver Cascade, Bridal Veil Falls, Near the Present Site of the University of Minnesota" Hennepin County Digital Library, 1860. https://digitalcollections.hclib.org/digital/collection/p17208coll18/id/30/rec/12

- "Bridal Veil Falls" Help Me COVID, 2022. https://www.helpmecovid.com/us/3454363_bridal-veil-falls

- "Two men at Shadow Falls, St. Paul, Minnesota." Macalester College, Accessed September 8, 2022. https://collection.mndigital.org/catalog/macal:49

- Rathburn, Betsy. "The Hidden Park that will Make you Feel Like You've Discovered Minnesota's Best Kept Secret" Only In Your State, January 16, 2017. https://www.onlyinyourstate.com/minnesota/hidden-park-mn/

- McDermid, Kim. "Climbing in Crosby Park, Twin Cities Ice (MSP/STP)" Mountainproject.com, https://www.pinterest.com/pin/crosby-farm-regional-park-slot-canyon--370984088058139612/

- Holdridge, Mark. "Ivy Falls" Google Maps, Accessed September 6, 2022.

- Hickson, Thomas. "Glacial River Warren and the retreat of St. Anthony Falls" Carleton.edu, https://serc.carleton.edu/vignettes/collection/25473.html

Read More:

Stay in touch

Sign up for our free newsletter

More from Racket

MN GOP Lawmaker: Do You Want a House or Do You Want Capitalism?

Plus weed party woes, Clark loved the Lynx, and a safe driving tip in today's Flyover news roundup.

Let’s Review Taco John’s New Taco Pizza, a Triumph of Messy, Unnecessary Midwestern Fusion

A gimmicky 'za worthy of Whiplash.

The 12 Best Neighborhood Intersections in St. Paul

Lexington & Grand, Chavez & State, and more of the Saintly City's crucial corners.

The 13 Best Neighborhood Intersections in Minneapolis

Forget Hennepin & Lake, let's talk about 38th & Grand, Xerxes & 50th, and 42nd & 28th.

Never Miss the Mountain Goats Because the Mountain Goats Never Miss

This past weekend in St. Paul, John Darnielle and his crew were at their most stirring.