No long fancy intro over here. If you wanna hear my extended thoughts on the year that was, they're collected over here. If not (your loss!), dive in to my list of faves below.

When deciding what year a movie belongs to, I go by when it was released or at least screened in Minnesota. That means you’ll find a couple entries that fancy coastal critics would call “2023 movies” on my list, while there are a few highly celebrated movies (such as The Brutalist, Nickel Boys, and the one I’m really looking forward to, Mike Leigh’s Hard Truths) that I won’t get to see until you do, this year.

25. Flow

Every house cat stalks through its domain like some fierce jungle predator indifferent to any challenge. Latvian animator Gints Zilbalodis calls that supposedly independent beast’s bluff, tossing a kitty into a flood and asking, “How tough are you now, huh puss?” Flow is in part a unique hangout movie, a kind of a postdiluvian animal Real World where a prickly black cat is forced to coexist on a boat with a wounded secretarybird, an acquisitive lemur, a stolid capybara, and an all too friendly Lab. None of the critters speak—aside from knowing how to work a rudder, they generally behave as animals would. And while the computer animation isn’t exactly beautiful, and can’t avoid an occasional cutscene quality, we pass through computer-generated environments with an unmatched three-dimensional ease that's its own reward. Though we never learn what happened to the humans—Flow is blessedly free of any backstory—there’s also an element of wish fulfillment here. If humans ever do finally off themselves en masse, it suggests, at least the animals we love will find ways to survive. If they learn to work together better than humans did, that is.

24. Civil War

Alex Garland’s alt-history war flick is a very easy movie to pretend to think about, and the crosscurrent of opinions has proven once again that people are very bad at watching movies—are maybe not even sure why they watch movies to begin with. I’m sure you know the set up: The U.S. has splintered into four warring factions, and we’re not told why. (The absolute lack of world-building is an overdue slap in the face to loremongers and Vox explainer culture.) Kirsten Dunst is Lee Smith, a legendary photojournalist undergoing a crisis of conscience; Cailee Spaeny (so fresh-faced she looks like she cut chem lab to be there) is the young wannabe who latches onto her. Together they trek to D.C., hoping to arrive before it falls to insurgents, and they experience a string of Apocalypse Now-style episodic grotesqueries along the way. Like most modern war movies, Civil War thinks it’ll disabuse us of our romantic notions of battle; like most successful war movies, it works as entertainment rather than ethical treatise. We don’t want rocket launchers actually fired into the Lincoln Memorial any more than we actually want Tokyo to be flattened by giant lizards or teenage girls to be butchered by psychopaths. We want images of our anxieties and desires displayed in a context where we’re free of the moral obligation to decide which are the anxieties and which are the desires, because what’s happening is “just a movie.” Civil War is a film rightly distrustful of the power of images that nonetheless relies on the considerable power of its own images to work. Fortunately, nobody has ever said horror movies had to be ideologically coherent.

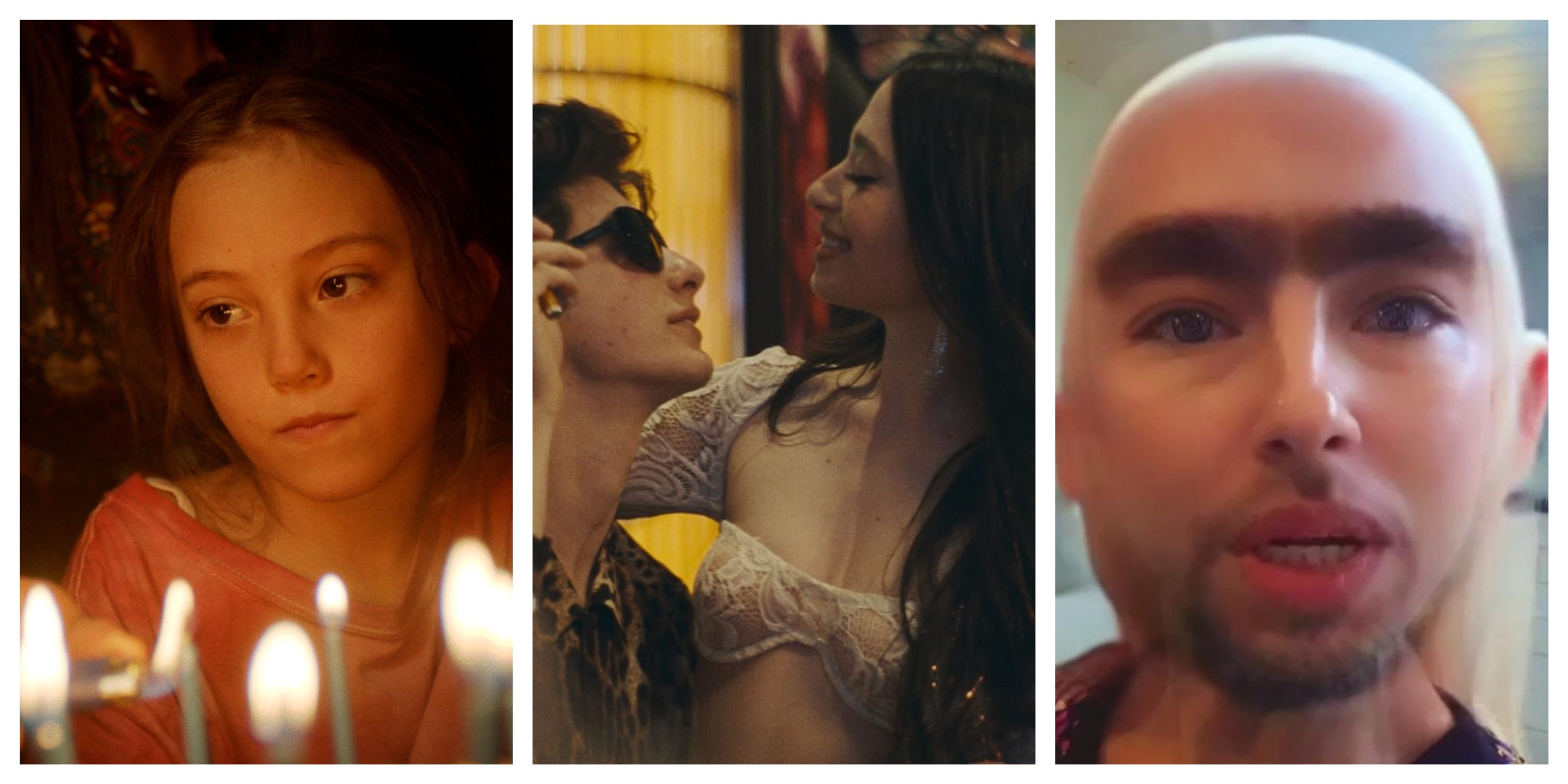

23. Janet Planet

The directorial debut of acclaimed playwright Annie Baker is an uncommonly nuanced (if slightly playwrighty) telling of a not-uncommon movie subject—the life of a sensitive and intelligent child raised by a caring but woo-woo parent. Julianne Nicholson is the single mom, and Zoe Zigler is her 11-year-old daughter, Lacey, and both are terrific. The film is structured by the entrance and exit of three people in Janet’s life: a boyfriend named Wayne, an old friend named Regina, and a spiritual puppeteer named Avi given to high-flown pronouncements. Possessive of her mother, Lacy resents each of these interlopers, with various degrees of appropriateness. (I wouldn’t want Avi anywhere near my mom either.) But along the way, without the clamor of any hackneyed cinematic epiphanies, the girl develops an awareness of her mother as a flawed but real person, a woman Baker presents to us without blame but without excuses.

22. Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga

Prequels, to use a technical cinematic term, suck. But if Origins of Furiosa is the movie George Miller has to make in order to shred more dudes underneath the wheels of a giant truck in a desert, who am I to complain? Anya Taylor-Joy is winningly stoic as the title character, Alyla Browne even better as her even younger self, and Tom Burke (the posh junkie from Joanna Hogg's The Souvenir) is gallant as somebody named Praetorian Jack. As for Chris Hemsworth, still making good use of his freakishly enhanced Asgardian physique, he gets a few too many bits of scenery caught in his teeth as he chomps his way through the wasteland, but that's part of the fun. Worth it alone for the War Rig battle, the kind of sequence literally no other director would even think to film even if they knew how.

21. Gasoline Rainbow

I’m a simple man. You set some restless yet good-hearted teens loose in a movie and I’m gonna root for ’em. Here five small-town Oregon kids decide to celebrate the end of their youth by trekking out to the Pacific, and along the way they act their age, waxing lyrical about their friendships and the passage of time while also shit-talking and flirting a little. You could almost mistake Gasoline Rainbow for a documentary (if an unusually lyrical one) because that’s the Ross brothers’ style, as fans of their affecting 2020 overheard-in-a-barroom breakthrough Bloody Nose Empty Pockets already know. Gasoline Rainbow has nothing to do with “Gen Z,” whatever that is, and everything to do with these five particular kids, but there’s something political about this film, and not just because there’s something political about any American art that takes teens seriously for a change. You sense a world tightening around these wanderers, and the decent eccentrics they meet along the way, a shrinking of possibility that they're aching to defy for as long as they still can.

20. Dahomey

A voice that booms out from the darkness, disoriented, belonging to a statue plundered from an African kingdom long ago, now among 26 such pieces that are returning from France to Benin. Such flourishes aside, Mati Diop’s documentary about the repatriation of African art begins matter-of-factly, following as the art is crated and shipped and unpacked, a close, even clinical study of process. It’s the second half of this film that addresses the many questions the subject raises, and without resorting to talking heads. Whose art is this, really? Does it really belong in a museum? Why is the state treating the return of such a small portion of its stolen goods as a political triumph? Watching the young people of Benin knowledgeably debate such matters in an open forum makes Dahomey as engrossing as most dramatic features I saw this year. Set that segment alongside the community meeting in Evil Does Not Exist (see below) as striking film examples of what democracy sounds like.

19. Between the Temples

The setup is a little too much like a movie pitch: Jason Schwartzman is a cantor unable to get over his wife’s death; Carol Kane is his old music teacher, who demands that he prep her for a late-life bat mitzvah. But though these two characters do indeed, you know, “learn a little about each other—and themselves—along the way,” Nathan Silver’s understated little comedy (co-written with C. Mason Wells) is unconventional in a lived, everyday sort of way rather than willfully quirky. (It’s also a welcome peek into a middle-class community of Jews who for once aren’t depicted as screaming neurotics.) Great cast, for sure: Cantor Ben’s two moms are noodgy Dolly de Leon (even better here than in Ghostlight) and matronly Caroline Aaron (you’ll recognize that gravelly voice), while Robert Smigel is an easygoing rabbi and Madeline Weinstein is his daughter, who everyone wants Ben to marry. But it’s Schwartzman and Kane, both wizards of cadence, who carry the film, their relationship developing along a comic, conversational rhythm that’s complemented by Sean Price Williams’s trademark handheld verite style.

18. Robot Dreams

A Wild Robot was fun, if a bit message-heavy in the way quality mainstream animation often is nowadays, but my droid toon of the year cut a little deeper. A lonely dog sends away for a robot friend, and the two new pals have a blast together. Then an outing at Coney Island leaves the bot rusty and immobile and the pup has to abandon him there for the winter. Both are forced to survive on their own, and the film follows a few unexpected narrative and emotional turns. It’s hard to think of an adult movie last year that took friendship this seriously.

17. Fallen Leaves

In Aki Kaurismäki's take on a romcom, two middle-aged, taciturn, and presumably lonely Helskinians (played by Alma Pöysti and Jussi Vatanen) toy with the idea of falling in love, their decision delayed by their own recalcitrance and the quirks of fate. Vatanen has Jimmy Stewart’s drawn good looks without his warmth or prickliness. Pöysti has an even more impassive face, and her rare moments of expressiveness aren’t instances of spontaneity slipping through her mask; it’s as though she has to will them to occur. Both are ideal for this formalist little movie, with every line, every action, and every reaction in its right place as it winds its way toward as happy an ending as the Finnish temperament allows. Read our full review here.

16. About Dry Grasses

You’ll encounter few main characters as instantly unlikeable as Deniz Celiloğlu’s Samet. A teacher stationed in east Anatolia (a.k.a. the sticks) as part of his Turkish national service, the grumbling snob distracts himself from the tedium of his position by flirting with his female students and, when he notices his colleague is attracted to a woman, wedging himself into a love triangle. At 197 minutes, this is the sort of film that gets euphemized as “unhurried,” and while it may feel perverse comparing such a sprawling feature to the work of a short story master, it's as Chekhovian as some critics have said. As always in the work of Nuri Bilge Ceylan, the real tension comes from the way the petty concerns that play out are dwarfed by the immensity of the natural surroundings.

15. Love Lies Bleeding

If you head in to Love Lies Bleeding to watch Kristen Stewart and Katy O’Brian fuck each other and murder dudes—and that’s reason enough—you will not be disappointed. In true noir fashion, Jackie (O'Brian) is a drifter, en route from an Oklahoma childhood to a bodybuilding competition in Vegas, stopping off in New Mexico because that’s the sort of place these stories happen. Here she meets Stewart's Lou and the bodies start to hit the floor. As the knot tightens around the lovers, generating a titillating claustrophobia à la Jim Thompson, the question becomes whether Lou’s brains will save Jackie, Jackie’s brawn will save Lou, or theirs is the sort of love that dooms them both. Not till the final scene are the roles they’ve chosen to play in this relationship finally clear. (Love, the film seems to say, means never complaining about disposing of your sweetheart’s murder victims.) I’ll admit, for a half-hour or so I worried that director Rose Glass’s euphorically nihilist lesbian death trip was too nutty to be a good movie and yet not nutty enough to be a great one. After [SPOILER REDACTED], that concern just felt silly. Read our full review here.

14. Me

A bean-like man boots his family and in his solitude invents an award-winning machine powered by narcissism. A boy encourages his disturbingly eye-shaped brother to levitate off into space. A creature stripped bare to its nervous system regales the vacant cosmos with an aria. In the best short film of 2024, Don Hertzfeldt’s glorified stick figures consistently find ways to retreat into themselves, as cops batter citizens and shriveled corpses are dumped into trenches. But always the weird and unexpected intrudes, always the animator's background flashes and glitches and hand-drawn static sync disconcertingly with the music, whether that's Mozart or Jelly Roll Morton. A truer sketch of human consciousness than the corporatized determinism Pixar peddled in Inside Out 2, that's for sure.

13. I Saw the TV Glow

As with her debut, We’re All Going to the World’s Fair, writer/director Jane Schoenbrun reconfigures the trans coming-out narrative as a horror story, as open to peril as to promise. Two teens growing up in the ’90s bond over a Buffy-style show; as the edges of supposed fiction and supposed reality blur, the knowledge they gain about their potential selves brings suffering, whether they accept or retreat from that insight. A jarring remix of ’90s kid culture, recollected in something less than tranquility, I Saw the TV Glow reinstates the TV as the box of ominous mystery it once was, solid enough not just to represent other worlds, but to contain them. The weird is familiarized, the familiar is enweirdened. And in Brigette Lundy-Paine and Justice Smith, Schoenbrun has two leads who know how to communicate within a Lynchian blend of heightened mood and flattened affect. Read our full review here.

12. La Chimera

Alice Rohrwacher's latest follows the exploits of some Italian grave robbers who specialize in plundering Etruscan tombs, as guided by the mystical gifts of a rumpled British ex-con named Arthur (Challengers' Josh O’Connor, who does rumpled better than anyone this side of Clive Owen). Arthur's real search, however, is for his beloved Beniamina, the details of whose existence remain a mystery. His quest does give us an excuse to spend time in the presence of her wonderfully dotty mother (Isabella Rossellini, who does wonderfully dotty better than anyone). Rohrwacher's absurdism is loose and light, more fairy tale than Fellini, with a flair for rural naturalism that finds a striking vividness in the everyday and imagines utopian regroupings beyond the grasping politics of wealth. But there’s a profound sense of loss anchoring the film as well. Also from 2024, check out Rohrwacher's short Urban Allegory, where a 7-year-old boy in Paris imagines himself escaping Plato’s cave with a nudge from Leos Carax.

11. Evil Does Not Exist

If you asked me what Ryusuke Hamaguchi's follow up to Drive My Car is about, I’d say that a Tokyo company plans to open a glamping resort in the village of Mizubiki, and the villagers, quite reasonably, would prefer that their environmentally unspoiled location not become “a tourist hot spot.” The dramatic highlight of the film is an uncomfortable information session company reps present to the townspeople—a public fantasy of how every true democrat imagines a community meeting functioning, and also a kind of private wish fulfillment for anyone who’s ever stammered when finally given the opportunity to speak their mind to the powerful. But It might be more accurate to skip past the central conflict entirely and call Evil Does Not Exist a movie about a man quietly performing simple tasks with precision and duty. As Takum, Hitoshi Omika is hypnotically opaque, hiding his thoughts from us while his actions, when not routine, are unexplained. Or maybe it's about the relationship between cinematographer Yoshio Kitagawa's shots of the forest outside Mizubiki and Eiko Ishibashi’s score, which seems to notice how we’ve responded to the images on screen and whisper, “Are you sure?” Or it may just be about the feeling you have upon leaving the film: like waking up slowly, failing to recall exactly where your subconscious took you last night, and finding yourself unable to shake the feeling that something awful really has happened. Read our full review here.

10. My Old Ass

Aubrey Plaza is the subdued, grounded foil that enables a breakout performance from 20-year-old Canadian actor Maisy Stella. (Maybe you remember her from the TV show Nashville. Maybe you don’t.) Both women play Elliott Labrant—Stella as a teen, Plaza as the 39-year-old incarnation that her younger self inadvertently summons on an 18th-birthday mushroom trip. As Young Elliott endures her last summer on her parents’ cranberry farm before moving to Toronto for school, her older, wiser self tutors her on how to live. (Ah, but which version of Elliott will truly learn a lesson about life?) Like all film messages, My Old Ass’s call to be “young and dumb” is one only some of us need to hear some of the time. But that’s often enough. And as shallow as the cliche “you’ll laugh, you’ll cry” may sound, those were the two things Aristotle wanted theater to do to us, you know. What’s more, writer/director Megan Park recognizes that no honest coming-of-age movie today can ignore the fact that the future will be hard in unimaginable ways. I only wish that My Old Ass had been released in summer, when it still had time to emotionally crush graduating seniors who thought they were ready to leave their parents behind. Read our full review here.

9. Daughters

Every year, Angela Patton’s Camp Diva holds a special Daddy Daughter Dance—in prison. Patton and filmmaker Natalie Rae follow four inmates of a D.C. institution and their daughters as they prepare for this event. One girl has never met her dad and is processing her mother’s lack of faith in his ability to change; another girl has hardened to an (understandable) distrust of all adults. And I will never forget the emotional path travelled by adorably chatty 5-year-old Aubrey Smith, whose obsession over how long her dad will be away feeds into her love for math. But though Patton is co-director, and sweetly weepy moments abound, Daughters isn’t purely inspirational. As in any good doc of this kind, you can’t always tell where its subjects will end up, and the filmmakers never gloss over the pain these girls have suffered, the guilt these men experience, and the difficulty of reform in the world as it is. Even an honorably crafted story of men learning about themselves in prison like Sing Sing feels stagy in comparison.

8. A Different Man

Gotta love when a looker like Sebastian Stan prefers to go freak mode. Stan begins Aaron Schimberg’s wonderfully mean little comedy heavily made up as Edward, a man with neurofibromatosis (his face is overrun with tumors). He’s certain his condition has kept him from becoming a successful actor and from winning the love of the cute playwright next door (Renate Reinsve), so when a cure presents itself, he undergoes a trial procedure and is reborn as Guy—Stan sans makeup. But inside he’s still the same ol’ schlub, and he’s showed up by the arrival of Oswald (Adam Pearson, an actor with neurofibromatosis in real life), a real charmer who proves that babes really do just want a guy with self-confidence and a sense of humor, just like they always say. The Seb Stan-ce, the great writer Demi Adejuyigbe calls this admiringly on Letterboxd, while another poster more bluntly calls it “The Substance for boys,” and kinda true on both accounts. But it’s funnier, more disciplined, and, in its quiet way, nastier than that celebrated gorefest—imagine if Charlie Kaufman had genuine perspective on his own self-pity instead of ducking behind infinite metanarratives.

7. Perfect Days

In Wim Wenders's latest, Hirayama (Koji Yakusho) is an elderly man who cleans public toilets in Tokyo with dutiful care. In his work and in his free time, he hews to a routine so strict that every slight deviation over the course of the film feels seismic, to him and to us. He doesn’t exactly shrink from human contact—he bonds with his irritating young co-worker’s would-be girlfriend while listening to Patti Smith’s “Redondo Beach” and plays shadow tag with a dying man. But his existence is largely self-contained, and this is one of the rare films to show that a life lived alone is not necessarily lonely and certainly isn’t meaningless, though like any life it comes with its own regrets. Hirayama is open to beauty in every moment (during his breaks he photographs the way the sunlight hits the leaves) and so is Wenders. In fact, I would say that Perfect Days captures the unbearable joy of being alive if it didn’t make me sound like a pretentious sap. Fortunately, the closing sequence, as we watch an array of emotions flickering across Yakusho’s face, makes that point for me without using any words.

6. Red Rooms

In a year of films that aspired to inspire dread, only writer/director Pascal Plante’s sleek story of interlocking sociopaths stirred that genuine queasiness in my gut that I might witness something I couldn’t unsee. A man is on trial for mutilating and killing young girls for live online subscribers in a dark web “red room,” and each morning, two women camp out to grab seats in the courtroom. Clementine (Laurie Babin) is a gabby groupie from the provinces, certain of the defendant’s innocence; Kelly-Anne (Juliette Gariépy), an icily unreadable model, seems more obsessed with one victim’s mother. Without offering some klutzy commentary on the subject, Red Rooms plays off the cultural fascination with true crime and how suffering plays out in the media. And its suspense is driven by our dual panic about surveillance: We fear that someone is always watching us and also that someone is committing unspeakable acts beyond our watchful gaze. I typically roll my eyes when critics talk about how viewers are “implicated” in whatever fictional brutality they’re shown, but Red Rooms really does feel like something we shouldn’t be watching, and Gariépy’s blank intensity makes her a terrifyingly unpredictable character—she seems truly capable of anything. For once I’m glad I watched this at home; in a theater, I might have hyperventilated and passed out.

5. Babygirl

I know many misguided youth feel deprived because Adrian Lyne’s alleged prime ended before they hit puberty, but take it from grandpa, erotic thrillers were rarely this self-assured in ye olde 20th century. Nicole Kidman is a tautly wound robotics exec who still packs her daughters’ lunches; Harris Dickinson is the intern who sniffs out the need to surrender beneath her hypercompetent sheen. And let’s not forget Antonio Banderas, who ably fills the traditional Anne Archer Hot Spouse role. What writer/director Halina Reijn gets about America’s official contemporary sexual ideology is that while no kink may be shamed—certainly not the fairly tame obedience training acted out here—sex with an intern is a taboo we daren’t treat lightly. And what Kidman captures in her performance, especially in the petulance that precedes her submission, is that every kink feels like an unimaginable transgression to the person first overcoming her shame. Kidman is a genuine auteur of self-degradation—truly, no one this side of Isabelle Huppert can match her freak. Yes, it’s “sometimes a bit much,” to quote a quibbling AP critic, which is like noting that “there are a lot of songs” in Wicked, but give in to your uncomfortable snickers, even if they emerge as full LOLs. The fun here is never knowing when to be turned on, amused, anxious, or outraged. As for Dickinson, he smolders so credibly as Samuel, a kid whose instinct for dominance outpaces his competence or authority, that I promise never again to confuse him with George McKay.

4. Totem

The adult world is a foreign country for children, who are tasked with consistently deciphering the speech and customs of grown-ups. Just ask Sol, a 7-year-old whose father, Tona, is dying of cancer, which she may not know, or may intuit but not quite comprehend. As played by Naíma Sentíes, a child gifted with a transparently but never excessively expressive face, Sol is also a detective of sorts, and director Lila Avilés’s deceptively artless handheld camera trails her as she gathers clues. Through Sol’s eyes, we grasp the chaotic life of a family, the physical details of the home she passes through, the traits and foibles of the family members she interacts with or brushes past, all familiar to her but new enough to retain their strangeness. They're preparing for Tona’s birthday party, which will double (though this is left unsaid) as his farewell party, adding an edge to the bustle, so the distracted adults mostly leave Sol alone to explore. Totem may be as close to feeling 7 as you can ever come again, in all that age’s wonder and confusion and newly felt pain.

3. All of Us Strangers

This is Andrew Haigh’s idea of a ghost story, and the specters roost inside our heads, where they can seem more real than the material world outside. They can allow us to make peace with the past, or they can lure us away from our lives into deceptively comforting fantasies. Andrew Scott is Adam, a solitary gay screenwriter old enough to remember the AIDS epidemic and Frankie Goes to Hollywood. While writing about his parents, who died in a Christmas Eve car crash when he was 11, he pictures them so vividly they come to seem more real than his everyday life. He also falls for his neighbor Harry (played, in a bear hug of a performance, by Paul Mescal, just in case you thought this was gonna have a happy ending), though we’re also left to wonder how many of their interactions might simply be imagined as well. Ultimately All of Us Strangers suggests that everything we need to make us complete is already within us—and that this might in fact be the saddest fact imaginable. Read our full review here.

2. Do Not Expect Too Much From the End of the World

This cynical, interminable, glitchy, hilarious mess of a film demands in-theater viewing, so you’re trapped with Ilinca Manolache’s exhausted Angela as she battles Bucharest traffic all day en route to screening machinery-mangled factory workers who compete for a spot in a workplace injury PSA. In her spare moments (she has none) she makes TikToks as her sexist alter ego Bobita, a would-be Andrew Tate who spews jokes about sluts into the void of the manosphere. “I criticize by way of extreme caricature,” Angela tells one detractor, essentially speaking for director Radu Jude, who immerses us in the sewers of contemporary life, where our fantasy worlds feel as cheap and compromised as our real lives and everything we do to survive places us more securely under the control of the powerful. Throughout, Jude ransacks film history for a point or a punchline: The Lumière bros are namechecked as cinema’s first sellouts, an ’80s communist propaganda film about a female cabbie (named, yes, Angela) feels grimly nostalgic, even Uwe Boll gets a cameo. And his finale is so comically, brutally tedious that a few people walked out of the MSPIFF screening with just 10 minutes to go. Cowards.

1. Anora

Mikey Madison’s Ani may be the most fully realized of writer/director Sean Baker’s high-powered, self-deluded survivors. A stripper and occasional escort whose charm and sheer self-determination have never failed her, she’s eking out a life in Brooklyn’s least-glamorous southern reaches. (Sheepshead Bay, Brighton Beach, and Coney Island are captured in all their drab, offseason outer-borough-ness.) Her life changes after a dance for Ivan, a Russian oligarch’s son, parlays into a paid fuck, which in turn goes so well he hires her for an extended stint. Baker captures their whirlwind spree through all forms of excess, ending with a Vegas wedding, as an audiovisual sugar rush that makes Pretty Woman’s shopping montage look like amateur hour. But when Ivan’s parents sic his handlers on him, he runs off like the spoiled little fuckboy we always knew he was, leaving Ani to match wits and brawn with the hired muscle as they go on the hunt. This decade, we’ve seen plenty of commoners enter the worlds of the wealthy, tales that often ended with grand fantasies of vengeance. Anora’s trip through the looking glass ends on a note of ambiguous solidarity.

Runners up (#26-50): The Settlers; Green Border; Chicken for Linda!; Exhuma; In Our Day; Girls Will Be Girls; Nowhere Special: Ghostlight; My First Film; Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell; Swamp Dogg Gets His Pool Painted; How to Have Sex; The Taste of Things; Dìdi; On Becoming a Guinea Fowl; Good One; Copa 71; Sugarcane; Challengers; Dune: Part Two; The Bikeriders; Maxxxine; Oddity; The Old Oak; Crossing.