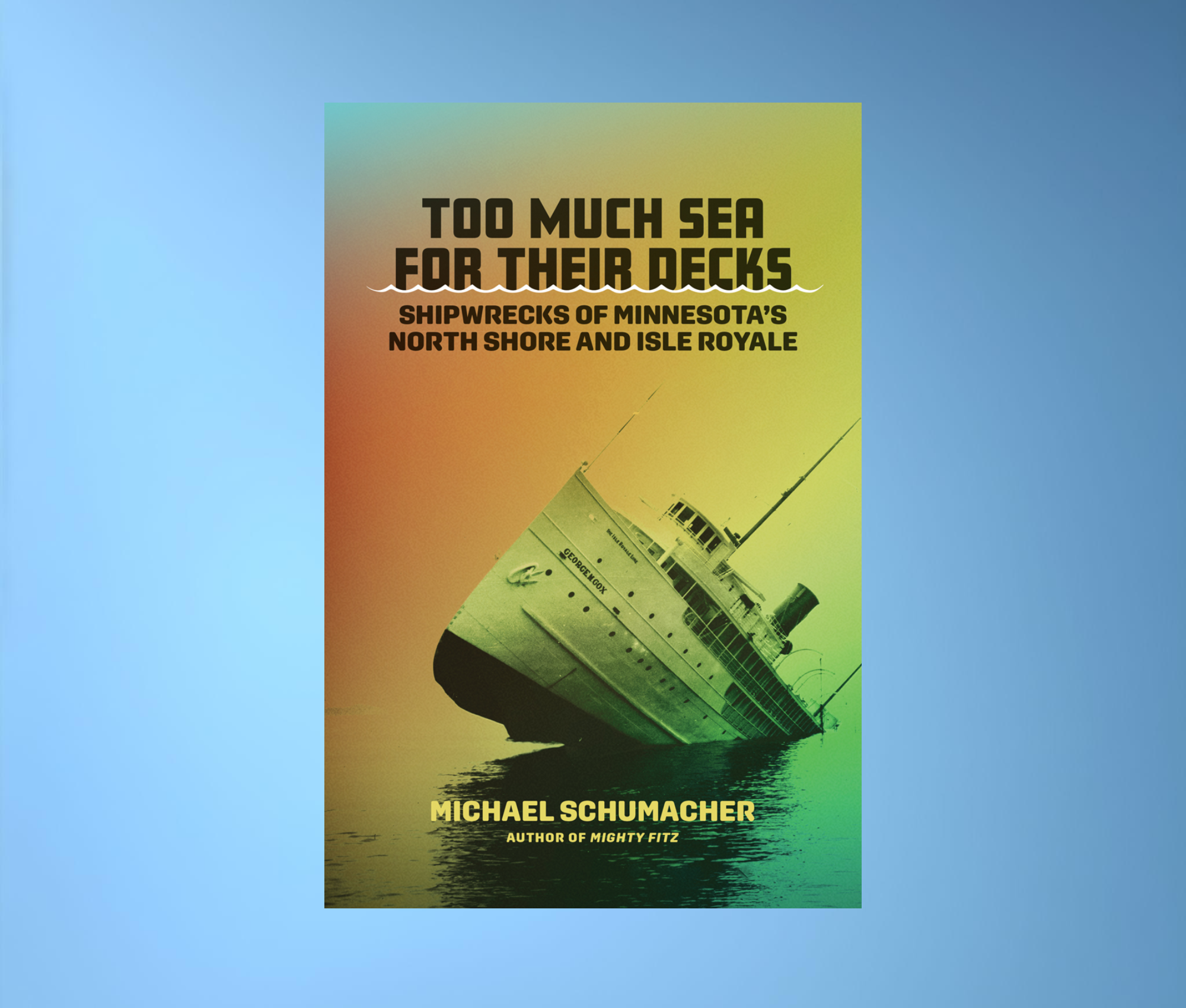

The following is an except from Too Much Sea for Their Decks: Shipwrecks of Minnesota's North Shore and Isle Royale, Wisconsin author Michael Schumacher's just-published historical account of Great Lakes shipping disasters. His dramatic new book "chronicles shipwrecked schooners, wooden freighters, early steel-hulled steamers, passenger vessels, whalebacks, and bulk carriers—some well known, some unknown or forgotten—all lost in the frigid waters of Lake Superior," per the University of Minnesota Press.

Enjoy!

Introduction: The Tragic Mysteries of Lake Superior

On the right day, when the sun is hitting the Earth at the perfect angle, when warm air is just enough to ruffle stray leaves scattered on the ground, when tiny waves are small enough to make you squint to see them, the northern shore of Lake Superior feels like magic. Old, battered bluffs rise on the horizon behind you, witness to the countless millennia that created this place. The lake runs on for as far as the eye can see, and the frigid water does not invite the casual swimmer, but for those brave and sturdy enough to test it, the depths can go from shallow to very deep in just a few strokes.

Lake Superior feels like the soul of North America. Its 31,700 square miles of surface area make it the largest freshwater lake in the world, and at its deepest point of 1,333 feet it is one of the deepest bodies of water in North America. Huge glaciers carved out the enormous areas occupied by the Great Lakes today; when time and moderate temperatures melted the glaciers, the ice, now water, filled the cavernous areas gouged out by the glaciers.

The dramatically uneven lake bottom, with its high and low spots often in proximity, contributed to the formation of numerous islands, including the cluster known as the Apostle Islands, and off Minnesota’s northern shore an archipelago of islands that include, notably, Isle Royale. These islands presented all kinds of navigational hazards after commercial shipping had become predominant in the mid- to late-nineteenth century.

The Ojibwe and other Native people understood the lake’s temperamental nature, especially in the fall, when the conditions around and on the lake can change in minutes. Rarely straying far from the shore, the Native people traveled in canoes that moved easily across the water and could swiftly head back to land if winds whipped up the water. Trade items included furs, food and provisions, and the minerals plentiful in the region.

The French were the first Europeans to explore the lake, called Gichigami by the Ojibwe, and the shores around it, but following their victory in the French and Indian War, the English renamed the lake Superior and controlled traffic on the water. Oddly enough, given the enormity of the lake and its access to the large stretches of land in the United States and Canada, commercial shipping was slow to develop on Lake Superior. Settlements on the lake’s shores were small. The frigid climate did not encourage major development. That changed with the building of larger cities, not only around Lake Superior but near the shores of other Great Lakes. By the early years of the nineteenth century, there was a spike in the need for commercial shipping, which competed with growing rail systems.

The first commercial steam-driven vessel hit Lake Superior in 1847. By the time the rich iron ore deposits were discovered nearly a half century later, demands for shipping on Lake Superior had reached unprecedented heights. The port at Duluth could boast of being one of the largest in the United States.

This demand necessitated the designing and building of larger, stronger vessels. Schooners and wooden freighters, once dominant in shipping, gave way to steel boats, which at the time of their launching seemed indestructible. The occasionally violent weather, churning up gigantic seas, turned out to be a serious challenge, especially in the month of November, when blasts of cold Arctic air collided with water yet to be cooled from summer. Some of the lake had yet to be charted, and groundings were not uncommon. As lake traffic increased, so did the number of accidents.

The lake, as those who sailed it learned, could be both welcoming and hazardous.

This is my sixth book about Great Lakes shipwrecks.

Mighty Fitz is an account of the loss of the Edmund Fitzgerald, and The Trial of the Edmund Fitzgerald, a companion volume, contains documents related to the sinking, plus a lengthy oral history drawn from the Coast Guard hearings conducted immediately following the loss.

Wreck of the Carl D. tells the story of the Carl D. Bradley, a gigantic limestone carrier that broke in two during a fierce November storm on Lake Michigan in 1958. Four men managed to escape to a life raft. Two survived the night, braving heavy seas and hypothermia-inducing conditions.

The Daniel J. Morrell, an ore carrier, broke in two and sank on Lake Huron under similar circumstances in 1966. Torn in Two is an account of the tragedy in which four men climbed aboard a life raft and tried to survive frigid and stormy weather. One man survived, but only after clinging to the raft wearing just a peacoat and undershorts for thirty-seven hours.

November’s Fury, the story of the great hurricane hitting the lakes in 1913, involved many boats on all five lakes, all battling what is universally agreed to be the worst storm to ever hit the lakes, claiming more lives and vessels than seemed possible. Each tale of an individual boat is self-contained, yet each is part of a much larger story.

Each of these books has an essential individual theme that I hadn’t considered when I embarked on my research—a theme that acted like the keel of a vessel, the backbone on which everything else was built. Mighty Fitz, for instance, is a Great Lakes mystery. No one will ever know for certain why or how she went down. This became evident as can be in Trial of the Edmund Fitzgerald. Wreck of the Carl D. is a heartbreaking account of the small town of Rogers City, Michigan, which bore incredible suffering and loss; it seemed that everyone in the town was related to, or knew, one or more of the shipwreck’s victims. Torn in Two is about survival under impossible circumstances and the price exacted from a sole survivor. Finally, November’s Fury addresses more than a single storm: it studies the destructive forces of nature and how it possesses the ability, to quote Gordon Lightfoot, to “turn minutes to hours.” Anyone who has ever been in a wreck and survived will tell you that time freezes when you are struggling to live.

To me, those themes had the power to drive the story forward. I didn’t plan it that way; they simply presented themselves as the research and writing advanced.

This book is different. There is no single major undercurrent of a theme. Perhaps I subconsciously included the important aspects of shipwrecks in the other books—and they are important here—or maybe a theme hasn’t yet occurred to me. I don’t know.

Maybe the city of Duluth is the undercurrent in this book. Once second to only New York in handling commercial shipping traffic, Duluth figures, one way or another, in many of the accidents described here. Its harbor entrance, one of the most beautiful you will find anywhere, could be a challenge to vessels sailing in heavy weather, but, as the Thomas Wilson, a whaleback broadsided by another boat, learned at the beginning of the twentieth century, it didn’t have to be storming for a tragedy to occur.

But it isn’t just the shipwrecks that make Duluth memorable. Commercial shipping contributed to the city’s exponential growth near the turn of the twentieth century, and the shores of western Lake Superior, acting as foreground to the hilly northern Minnesota terrain, into which so many homes seemed to have been carved, have given Duluth a beauty that needs to be seen and experienced by anyone journeying through the area. I have been to Duluth many times, and all this was certainly on my mind when I was working on this book.

Or perhaps the history of commercial shipping acts as the keel of this book. The topic is far too large and general to be adequately addressed in a volume of this size, but it was on my mind throughout my writing. I hope to give the reader a taste, a flavor of the extraordinary history of Great Lakes shipping, whether that entails the discovery and development of the materials shipped, the boats carrying them, the passenger services, or the ways that weather services affected shipping. I consciously tried to include the many types of vessels plying their trades for more than a century, including schooners, wooden freighters, early steel-hulled steamers, whalebacks, and bulk carriers, as they increased in size and the amount of freight that they hauled.

An evolution was at work here. This history, in turn, greatly influenced the growth of an entire region of this country.

From the beginning, I envisioned a three-pronged approach to this book’s contents: the shipwrecks of Minnesota, particularly the state’s northern coastline; the wrecks in proximity of Isle Royale; and three storms of different character, all having a bearing on Minnesota and Lake Superior. Each of these three sections would be presented in chronological order, but each decade of the better part of a century is represented.

I originally planned to open with the storms. All were dramatic, plus we have a tendency to see storms as the main culprits behind ship sinkings. The storms chosen carry special significance in Great Lakes history. The 1905 storm (also known as “the Mataafa storm,” after the best-known vessel affected by it) exacted the greatest toll, in lives and material loss, in Lake Superior history; the tales of bravery and heroism in that storm are legendary in Great Lakes lore.

The storm of 1913 was indisputably the worst in the annals of shipping. Minnesota and Lake Superior were spared the worst—that horrible distinction goes to Lake Huron—but the impact on the area merited inclusion in the book.

The “Armistice Day Storm” of 1940 deserved inclusion not for its impact on Lake Superior (it was minimal, in comparison to other storms) but because of what it taught us about vicious storms and how quickly they could pop up, with devastating consequences. This was arguably the worst snowstorm to hit Minnesota, and the consequences, especially for duck hunters caught out in it, were lethal.

I ultimately decided that it might be best to present the storms last, to move from the specific to the general. This was mostly a matter of preparing the reader by offering history first, presenting the details about western Lake Superior and Isle Royale in the individual vessels’ stories rather than in accounts focused on a larger area.

Part 2, on Isle Royale shipwrecks, demonstrates my point. Although the island is large (45 by 9 miles), even combined with the tiny islands nearby it is still fairly small in the grand scheme of things. In a way, it is symbolic of nature, neither benevolent or malevolent, just consistent over the millennia, stamping its wonder on humans. It has been lethal at times. The topography of the lake floor surrounding the island rises and falls, leading to groundings described in this book. The island can be welcoming, violent, peaceful, unforgiving, relentless—as the unfortunate souls on the Kamloops determined, after escaping the clutches of a savage storm on a lifeboat and finding their way to Isle Royale, only to perish after they were isolated and exposed to the bitter cold. Encounters with hostile nature are part of a sailor’s job, an absolute they would prefer to avoid, one they usually conquer, but one in which they are occasionally defeated, as the thousands of shipwrecks littering the floors of the Great Lakes will attest.

The stories included here are the stories of loss.

Four of my previous books, about the losses of the Carl D. Bradley, the Daniel J. Morrell, and the Edmund Fitzgerald, examined founderings. All three sank in storms, though all on different lakes, and all three wrecks lie in two pieces hundreds of feet beneath the surface. The Fitzgerald was loaded with taconite pellets; the others were sailing light. All three vessels, the largest to sink in fresh water, provide varying perspectives on foundering.

This book, like November’s Fury, includes a mixture of sinking types, though the great percentage of losses in the 1913 storm involved cap- sizing, and this book, due to so many accidents occurring in shallow water near Isle Royale, reports largely on groundings. The reasons for the groundings varied, and I recognized during my research that this type of loss had a way of addressing human failings that preceded the losses. When examining the photographs of the boats aground, one can’t help but wonder how this sort of thing is possible. This book provides answers.

Although the shipwrecks in this and my other books are different and similar in many ways, one thing unites the sinkings: water. This is almost grotesquely obvious, but all you have to do is spend time around or on the lakes to feel the profundity in something so basic. I can walk from my house to Lake Michigan in a matter of minutes, and I visit the lake almost every day. I have also visited the other four Great Lakes many times. I am constantly reminded, especially during stormy times, of the sheer power of the water. I am also reminded, far more often, of the incredible beauty of the water, whether it is a clear, crystalline blue, or tinged light brown after the shallows have been stirred up by a recent storm, or is slate gray. And it goes on as far as the eye can see.

This is the mystique that brought so many sailors to their jobs. It’s not just the work and the money. One doesn’t have to work on a freighter for those. It’s something else.

Sometimes it’s soothing. And sometimes it destroys.

Excerpted from Too Much Sea for Their Decks: Shipwrecks of Minnesota’s North Shore and Isle Royale by Michael Schumacher. Published by the University of Minnesota Press. Copyright 2023 by Michael Schumacher. All rights reserved.