“People live by their stories—how can we use them to accelerate action on climate change?”

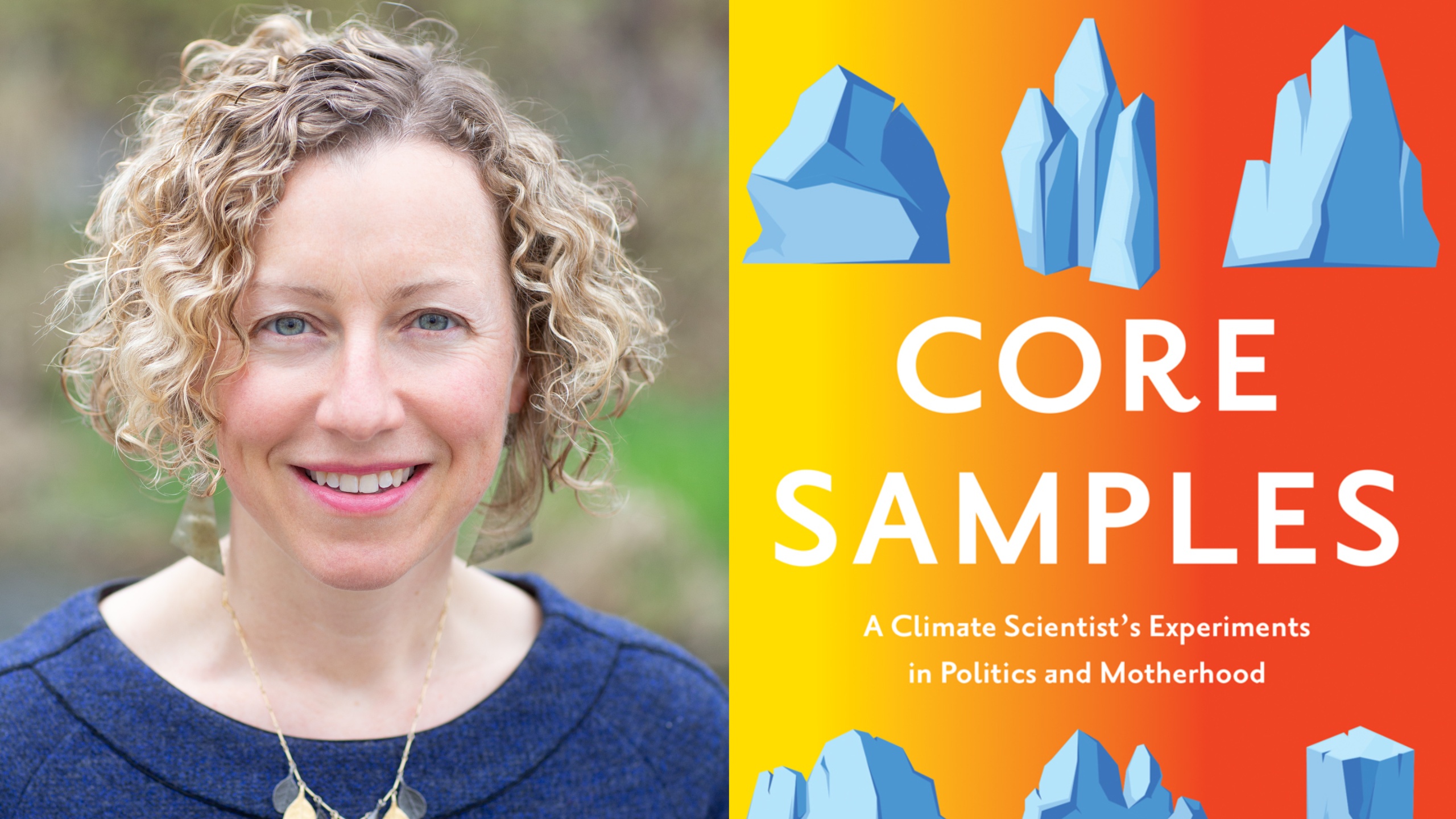

That’s the question Anna Farro Henderson sets out to answer in Core Samples: A Climate Scientist's Experiments in Politics and Motherhood (University of Minnesota Press, 208 pages). As a U of M scientist and policy expert who’s worked in Washington, D.C., but also been on field visits to nuclear test sites in New Mexico and the Juneau Icefield in Alaska, Henderson authored a book that's full of funny, poetic essays on politics, science, and motherhood, and the surprising places where those things intersect.

There will be a Core Samples launch event this Wednesday at 6:30 p.m. in the Open Book Performance Hall (1011 Washington Ave S., Minneapolis), which'll feature Henderson in conversation with Minnesota House Speaker Melissa Hortman. Books will be available for purchase from Magers & Quinn Booksellers, with live music preceding the talk and a book signing, interactive public art, and more music following it. (Free, but registration is required.)

View from the Lactation Room at the White House

We make fast friends—we’re both lost in front of our destination. The Eisenhower Executive Office Building, housing the executive offices of the White House, takes up four city blocks. It’s so large we don’t know where to enter. It looks like a cross between a castle and a spaceship, an architecture style called Second Empire.

“Women’s Energy Summit?” I ask, taking a guess.

We fall into step together, both anxious to not be late. In D.C., I talk to strangers everywhere: to find out why a train is delayed, because I like their scarf, without reason. This is a city of transients and compulsive networkers. People are as open to meeting as if we were all on a study abroad program. A colleague tells me that every conversation should be treated as a job interview, but for me it’s curiosity—I talk to strangers because I can.

My friend for the day, Jessie, is elegant in all the ways I am not. Her suit has a metallic sheen, it fits perfectly over her thin frame. She is shy, smiles flicker across her face and disappear. Runner’s legs float inches off the ground on snakeskin heels. Her perfection is made human by wild red curls moving in all directions.

My hair is similarly wild, but in contrast to her feminine sleek, I still look pregnant. My suit is too tight on the top and too big on the bottom—my breasts are oversize canteens of milk. I wear orthopedic black flats. My shoulders tilt, the unequal weight of a purse with notebook and business cards on one side, and on the other a weekend travel bag with breast pump and paraphernalia smashed in. Senator Franken hired me six months pregnant as a fellow on his energy, environment, and agriculture portfolio. Before taking maternity leave, I had just three months of briefing the senator, taking meetings, and researching policies. I’ve been back in the office for only six weeks.

I treat every conference like the apocalypse has happened and I’m forging a new life. Whether it’s a day or a week, I build a social network as if the event will last forever and I need a posse to survive. It’s like I can’t conceive of the ephemeral nature of folding chairs and scheduled keynotes.

Like Dorothy, I have three key characters in my postapocalyptic conference world. First, a confidante, the person to sneak out with and go sit in the sun. Second, a Madonna/mother figure, someone who will save me a seat and look out for me (and vice versa). Third, a homeland connection, someone with a tie to the outside world who offers a reality check. All this falls under networking, but my goal is just to feel comfortable.

For this one-day event, my confidante will be Joe, a twenty four-year-old man interning at the White House who I was told would have the key to the lactation room. My Madonna, Jessie with the red hair, will be the one to bring me into conversations with her large smile. My homeland connection is another scientist from my fellowship program. While I’ll never see the first two again, with the last I will share a Passover seder and swap emails over the next several years as we navigate ourselves out of D.C. and into more permanent lives.

The invitation from the White House is a beacon of hope, a signal that I’m going in the right direction. Up until eight months ago, I was on the path of a research scientist. I came to Congress through an American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) fellowship program that brings scientists into government.

In science, dressing up was wearing yoga or camping clothes—pretty much anything from REI. I never owned a purse and felt like a child who’d stolen her mother’s makeup when I tried to paint my face or nails. In D.C., everyone looks professional. This is the only place I’ve ever been where it doesn’t undermine women to look sexy—it doesn’t decrease how seriously people take them. These are the powerful, and no one is fucking around. In contrast to the sterile, slow, and silent isolation of science labs, policy is fast, a jazzy intellectual challenge of intensity and improvisation. I’m armed only with my background in botany and chemistry, the ability to read geologic maps, and my personality. I learn in the first week to run in heels, keep a poker face, and politely listen without committing to idealistic and impossible pleas.

While everyone in D.C., on any side of any aisle, talks about protecting American families, many don’t have children. D.C. is young and workaholic. People have kids in their late thirties, forties, fifties, or later. I often take Byrd, my three-year-old, to play with a friend at the park while his friend’s dad and I hang out. His friend’s dad is sixty-five.

Being pregnant in D.C. is another jump into the unknown. People ask, “You’re only thirty-two, and this is your second child?” And then the follow-up: “Are you religious?” Another fellow expresses her concern: “If you don’t go to happy hours, how will you ever get jobs?” I don’t bother telling her that at toddler birthday parties we also exchange business cards.

My fellowship program provided a month of training, a salary, and an evening mixer with congressional offices to kick off the interview process. Unleashed, entering the mixer, none of us certain what constituted professional attire, I had the fast-talking, big-smile feeling I imagine one has rushing a sorority. Except I was rushing a sorority six months pregnant.

In an interview with the lead office of the bipartisan climate and energy bill, I brought up being pregnant. I thought my interviewer, a male in his late twenties, might not have noticed. The spark of connection went out with him saying, “Yeah, well, you know, come January, I’m really gonna need someone up and running.” I had asked my AAAS program officer whether a dress with a suit jacket was equivalent to a suit. She said, “If you don’t have any clothes that fit you, just do your best.” I was advised to work for Guam or another nonvoting territory. Instead, I went full steam ahead. I didn’t bring up pregnancy again. These moments of negativity didn’t foreshadow what was to come for me.

I got offers, lots of offers. In many interviews, and with Senator Franken’s office, I met a new breed, those who believe working mothers are the same as everyone else. I waver on this. I’m shocked each time I slam into a physical boundary—pain, fatigue, hunger. Hunger without warning sometimes throws me off a cliff and leaves me shaky and confused. But these are obstacles that require acceptance and planning, not things that should prevent my being hired. Only I know what I’m up for and what is too much—and the answer to that is different for every woman.

The red-haired Madonna and I find the security line to enter the White House. “Well, my husband and John Kerry are very close,” she says. We’ve both worked in Africa on climate change, she in development, me collecting geologic samples. My field work experiences always offer some reliable connection to others. When I meet with lobbyists and other interest groups in Franken’s office, it creates intimacy to ask where in Minnesota they live or grew up, and then name a lake I have surveyed or cored near their town.

The beep-beep of a text message interrupts our conversation. I peek at my phone: “Just wanted to give you a heads-up, day care has put up a sign saying that several kids in Byrd’s room have lice.” I shove the phone into my purse and feel a flush of heat across the back of my neck. Dan will be home with the baby, Cluck, for the next three months. Byrd still goes to day care, living at a pace too fast for the sleepy quiet days of a new baby. I immediately feel itchiness on my scalp and imagine lice jumping on my curls like a trampoline.

We used “Cluck” as an in utero name, riffing off a T-shirt I once gave Dan. It says, “Sometimes love has a chicken’s face.” I bought it at the Wild Rumpus bookstore in Minneapolis, where cats and chickens roam freely among the bookshelves. My idea of a utopia.

We show our IDs to an armed man in uniform in a small guardhouse. “You cannot leave now that you’re in,” he explains.

“Your clearance is just for the one entry.” He sends us through a turnstile, and we wait on marble steps.

My phone beeps again. “You forgot a piece of your pump, should I bring it to you?” My stomach twists and I squeeze my toes and fists to remind myself to stay present.

We go through another security check with metal detectors. Uniformed officers open our bags. Of all the possible evils the scanner can detect, none can expose that I may be bringing lice into the White House.

A hundred women pack into ten rows of wooden chairs so tight our shoulders and legs touch. The room has several windows with white molding above and thick maroon blackout curtains. I imagine the lice, no bigger than sesame seeds, jumping from head to head. I consider that it might be reasonable to not want new mothers around. I cry more easily, I leak milk and smell like yogurt, I leave early to pick up my kids, and, now, I carry lice.

My husband texts, “Got pump parts, I’m outside. Guard says I can’t go in. Light rain, but able to keep Cluck dry.” It’s 10:30 a.m., and my breasts are filled with wet concrete. “I can’t leave and come back in,” I text. I need the intern with the key, and I need my pump part.

Community activists are on the agenda at 11:45 a.m., and I must pump before they speak. My breasts are a new frontier of emotion. Hot dampness catches me by surprise. My shirt soaked through by the news of a tornado in Oklahoma. Tragedy that before would have felt like a dagger to the heart now actually shoots pain from collarbone to nipple, leaving me breathless.

The new secretary of energy, Ernest Moniz, speaks to us. It’s his third day on the job. He’s had a fresh haircut since I saw him at his confirmation hearing. I step out just as an astronaut is about to speak. She is a leader at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), where I would love to work. I find Joe, the intern with the key. His smile is a smirk, but he doesn’t have the key. He has to go get it. I show him a picture of Dan and explain about the forgotten pump part. He skips down the stairs promising to be back.

“Hand off complete,” my husband texts five minutes later. I wait for Joe to reappear.

I talk farm bill in the hall with a lanky young man, also intern ing at the White House, also a male staffing this celebration of women in energy policy. We talk USDA. I ask where the lactation room key is kept, how long Joe might be. He shrugs.

This is the first time I’ve had to talk to a man about breast feeding, other than family or a medical provider. In the Senate offices, I’ve never had to explain my lactation needs. Other people get coffee, walk dogs, talk to their brother on the phone, and they don’t sit their supervisor down to explain themselves. It’s assumed that they, like me, take natural breaks in an intense workday. And the Senate is set up to accommodate pumping. A system is in place, so I’m not asking for what feels like a favor on a case-by-case basis. The Senate accommodates not only staff but also the public. A nursing mom can lobby her senator and then pump milk in a clean private room. The system assumes participation by lactating moms.

It took me months before I realized how many moms work in the Senate. I only heard about the Senate Mom Group from a chance encounter. The meetings are advertised by word of mouth. The first time I went, we gathered in the conference room of a senator from the extreme other end of the aisle from Franken. But for this hour, politics didn’t matter. Like fish gasping for air, we talked quickly. Women jumped from composure to tears without hesitation. I said little. I was overwhelmed by the fact that I wasn’t alone. I recognized colleagues in the room who I hadn’t realized were also moms. They talked about a husband with cancer, being in the groove of balancing everything, in-law complaints, in-law praise, taking cookware to a restaurant and paying for Thanksgiving sides to be packaged as if they were homemade.

Twenty more minutes go by. I peek in on the summit. I come back into the hall. Sweat soaks through my suit coat, and my breasts are harder than the marble walls. I’m still shocked at their size, my body as new and unknown as during puberty.

Joe hasn’t returned. It’s been an hour. I watch the end of the panel from the doorway, one foot in the room, one in the hallway. I try to imagine where in the ten acres of this office building the magical mothers’ room might be. And unlike the lactation room in the Senate, I’ve been told, it is just an empty room: no sink to wash hands, no fridge to keep milk cold, no hospital-grade pump to save lugging my own equipment around. Finally, Joe. He’s walking down the hall, smoothie in hand. “I can take you now.”

I follow him along the black-and-white diamond floor tiles. We skirt around a large crowd of men in dark suits. The ceilings are seventeen feet high, with light fixtures that belong in a Victorian dining room. The hallway is long, with white walls and evenly spaced doors. White pillars stand guard on either side of each door.

We take a turn, and another turn, and come back to where we started. Joe is starting to sweat too. He tosses his cup into a trash can. The building has two miles of hallways. This could take a while.

We go down a different hall. “I think we go up these stairs,” he says. He leads me up a spiral snail shell. Above the stairs is a dome with a twenty-foot-long stained-glass skylight of red, white, and mostly blue. Ornate gold-plated molding slides along the curve from skylight to wall. The natural light is bright and joyful, but I am shaky with the poison of milk sitting too long. Milk held in is like unexpressed anger. It can make you sick. I’ve had mastitis that started with the random thought of throwing up, and fifteen minutes later I was on the floor unable to stand. Breasts aren’t designed as long-term holding tanks. Especially in the early months following childbirth.

“Wait here!” Joe says, and he runs down the hall, a flash of black suit.

In a breastfeeding class someone asked where to pump if your job requires driving. “Church parking lots,” the teacher said. “They are a sanctuary, after all.”

He runs back, “Found it.”

I follow him through a small door and into a secret gnome hallway. While the floors in the main part of the building span seven black diamonds elbow to elbow, here they span just two. If I reach my arms out, I can touch the walls and the ceiling. The narrow galley bends and turns every ten to twenty feet.

Joe stops in front of a closed door. “Do you want me to wait outside?”

I feel the discomfort of a woman alone with an unfamiliar male in an alleyway. This isn’t a part of the building filled with people making the country run. This is where dusty things are stored.

“No thank you.” I slam the door, unable to ask the obvious. It seems ridiculous to staff a conference celebrating women with men—to task a young man with keeping the key to the lactation room.

Finally, my sanctuary. The critical link that connects all my education and work experience to all the potential I have to offer the world. In these early days of motherhood, lactation rooms are what keep me from falling off the sheer drop on either side of a steep path.

If I don’t pump during the day, my flow will dry up. While there are health benefits to breast milk, babies who drink formula also grow up bright, brilliant, and beloved. My commitment to breastfeed is based on the physical experience of a river of life flowing through me. To give that up would be a kind of spiritual death. Not rational, purely animal.

I enter the room so relieved I could barf. I might actually need to barf. But I don’t think these thoughts at that moment. Instead, I’m struck by the view.

The view from the lactation room at the White House is of the Washington Monument and the Thomas Jefferson Memorial, the Tidal Basin, and God’s clouds dark and fast across the blue sky.

The view is framed by just a small attic window, no decorative molding, a semicircle above a square of glass. There is indeed a fridge and a hospital-grade pump, and I understand that the conference organizers never bothered to check the room when I emailed ahead with questions.

But the curtains are open, and from up here D.C. is ribbons of forest weaving around expanses of prairie. Aside from the parked cars, it’s a timeless view. Nothing of the overcrowded streets and traffic. I push the window open, and in glides a cool breeze.

I throw my bag down on the gold-brown wall-to-wall carpet and lay out my supplies on a small table. I attach plastic flanges to bottles, tubes to pump, pump to electrical outlet. The setup of the pump recalls the muscle memory of setting up a science experiment in the laboratory. The results come with similar satisfaction, two or three or four ounces, measurable results. The pump runs, milk flows, and I close my eyes. I feel the sun and breeze, and, finally, I relax.

Lactation rooms are the rare places where I form memories. They are my “cigarette breaks.” While I often run on adrenaline, as if the whole of D.C. were a pool that has been electrocuted, during pumping breaks I slow down. It’s work to balance the city’s whirring with the soft skin and warm smell of a baby. It’s art to enjoy either of these on its own—let alone both together. The lactation room is a room to myself, a moment alone, a chance to pause.

Back at the summit, I clap for the panel I missed. I sit next to the Madonna—she has saved me a seat in a discussion group. Her hair tickles my cheek. I imagine a news story about John Kerry scratching his head the next time he delivers a speech, and the rumors that follow. About how only I will know it started with a hug between my son and me and then the quick leap of bugs from one curly head to another.

Later that night, my husband runs a metal nit comb through my hair. When he doesn’t see jumping throngs of lice I make him look again. At work the next day I scratch my head in a bathroom stall and clasp my hands to avoid scratching during meetings. I make my husband do another lice check. We shave off our son’s mop of curls. Everyone thinks we are preparing for the hot D.C. summer.

“You don’t have lice,” my husband tells me yet again. I glare at him, too afraid to let down my guard.

It takes a couple of days for the phantom itching to stop, for me to realize we are lice-free. We always were. I go into the day care main office and ask about the lice.

“Lice?” the director asks. “We put those signs up two months ago. You only noticed them now?”

Excerpted from Core Samples: A Climate Scientist’s Experiments in Politics and Motherhood by Anna Farro Henderson. Published by the University of Minnesota Press, 2024. Copyright 2024 by Anna Farro Henderson. Used by permission.