When I was a kid, I was obsessed with Gary Paulsen.

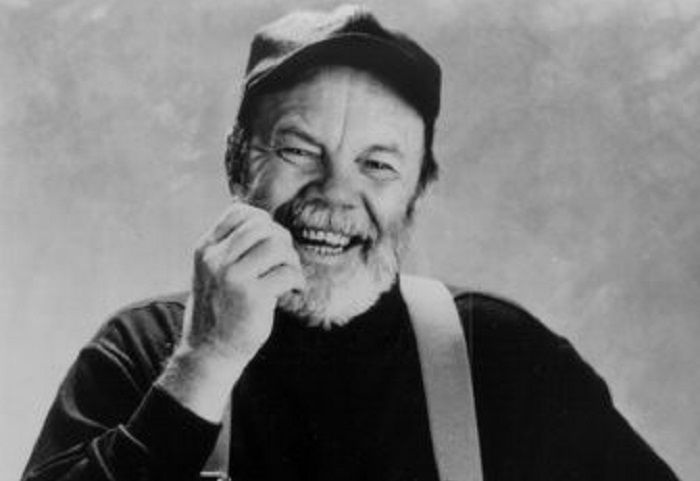

Specifically, I was obsessed with one series of Paulsen’s books. It wasn’t Hatchet, (though I did love Hatchet); I was obsessed with a series called Duncan and Amos (aka The Culpepper Adventures). I was a pretty lonely kid then, maybe eight years old, and Gary Paulsen got me. Looking back now, I think the author—who died of cardiac arrest last week at 82—could hit the mark because he had been a lonely kid too. He knew us.

Born in 1939, Paulsen spent his early years in Minneapolis and had a difficult home life: He moved around a lot, living with extended family sometimes. In January, he published his middle-school memoir Gone to the Woods: Surviving a Lost Childhood. In it, Paulsen talked about dealing with his parents’ alcoholism, and how the woods and reading saved his life. Paulsen was a self-made outdoorsman—he’s like Hemingway for pre-teens, but much nicer and tougher than Hemingway, and not a scuzzball. I didn’t know any of this back when I was eight, nor was my childhood anything like Paulsen’s had been. But I somehow understood that he got lonely kids, that he understood what we needed. Even in Hatchet, Paulsen’s most famous book, the main character Brian is alone in the woods; he’s dealing with solitude and being lonely as much as he’s dealing with survival.

The Culpepper Adventures weren’t about loneliness really, or at least not in an upfront way. Instead they were about friendship and zany adventures. There are 30 books in that series, all written between 1992 and 1997. The fact that there are 30 books in The Culpepper Adventures, and that you’ve probably never heard of them, speaks to how prolific Paulsen was as a writer—his bibliography includes around 200 books. My dad brought a Duncan and Amos book home for me from the library during my summer vacation: I tore through it, and subsequently every other Culpepper Adventure that I could find. This was the first time I’d ever experienced book magic: that feverish intensity, where you love a book close and fierce. This cryptic, alchemical feeling is strongest when you’re young; I would get emotional when the books were finished, I wanted more of their worlds. The feeling of needing to inhabit the liminal space of a piece of fiction was singular, significant, and new to me. It was also incredibly important to my literacy, a watershed moment in my development. Up until that point, I hadn’t really fallen in love with reading. These books were my catalyst.

Paulsen wrote about having a best friend the way that I wanted to have a best friend; the way that I longed to have a best friend. Today, I’m 35 and I still want a best friend like Amos, he’s a true ride or die. More than just vicariously having a friend though, the books taught me about mystery and three-act structure. In middle-school lit, the plot reveals hit you over the head, but it still feels earned. Duncan and Amos books are patterns in a way that you need when you’re in third grade, where you think to yourself, “I knew that was going to happen!” And that knowing feels special. I was still learning how to enjoy the experience of reading. I was dipping my toes in. The Culpepper Adventures worked on me because I wanted to be Duncan Culpepper, and I wanted to have a friend like Amos. I made myself one of them. In literacy and cognitive psychology, this is called “the Narrative Collective Assimilation Hypothesis.” When we read about kids at wizard school, we make ourselves a wizard with them, subconsciously choosing to be a part of the group. Paulsen’s writing let me pop into the world of Duncan and Amos and stand just behind them, one of the crew. At eight years old, I really needed that.

Nowadays, I teach freshman writing at a college. Before this, I taught in a transfer high school, which is a place where a lot of kids feel lonely. I sometimes feel like I understand lonely kids, as much as anyone can. My students all write beautiful literacy narratives at the start of every school year. They write about their history with reading and writing. Many of the narratives follow a similar arc. Like a romantic comedy it goes: child loves reading, then reading changes and child breaks up with reading; or more troubling, literacy as a skill, breaks up with them. As educators and writers, somewhere in the ephemera between little kid reading and adolescent reading, we’ve lost our way. The magic no longer translates for students and so they fall behind. I ask my students about “reading magic,” about feeling that fierce possessive love over a book the first time, like I did. More and more, my students tell me that they’ve never experienced that kind of love.

There’s myriad research now about how reading fiction is important in developing our brain’s empathy muscles. Our ability to orient ourselves in the consciousness of a character in a story? That builds out our ability to relate to and empathize with others in our community. Paulsen wrote books that help kids build those skills. He bridged the crucial gap between little kid reading and adult reading. His stories about overcoming hardship, about wilderness and resilience and friendship and independence, scaffold middle-school readers up toward the literary fiction and higher order cognitive tasks they’ll encounter later. This is vital in their development.

I was a kid who struggled with making connections to others. Paulsen’s books helped bridge the gap for me and taught me how to interact and belong. His books, and those empathic skills, are crucial to the wellbeing of our society. We need more Gary Paulsens. With 10 Paulsens, a hunting knife, and a box of matches, we could solve the literacy gap. We could maybe save the world.