Could a guitar amp be… haunted?

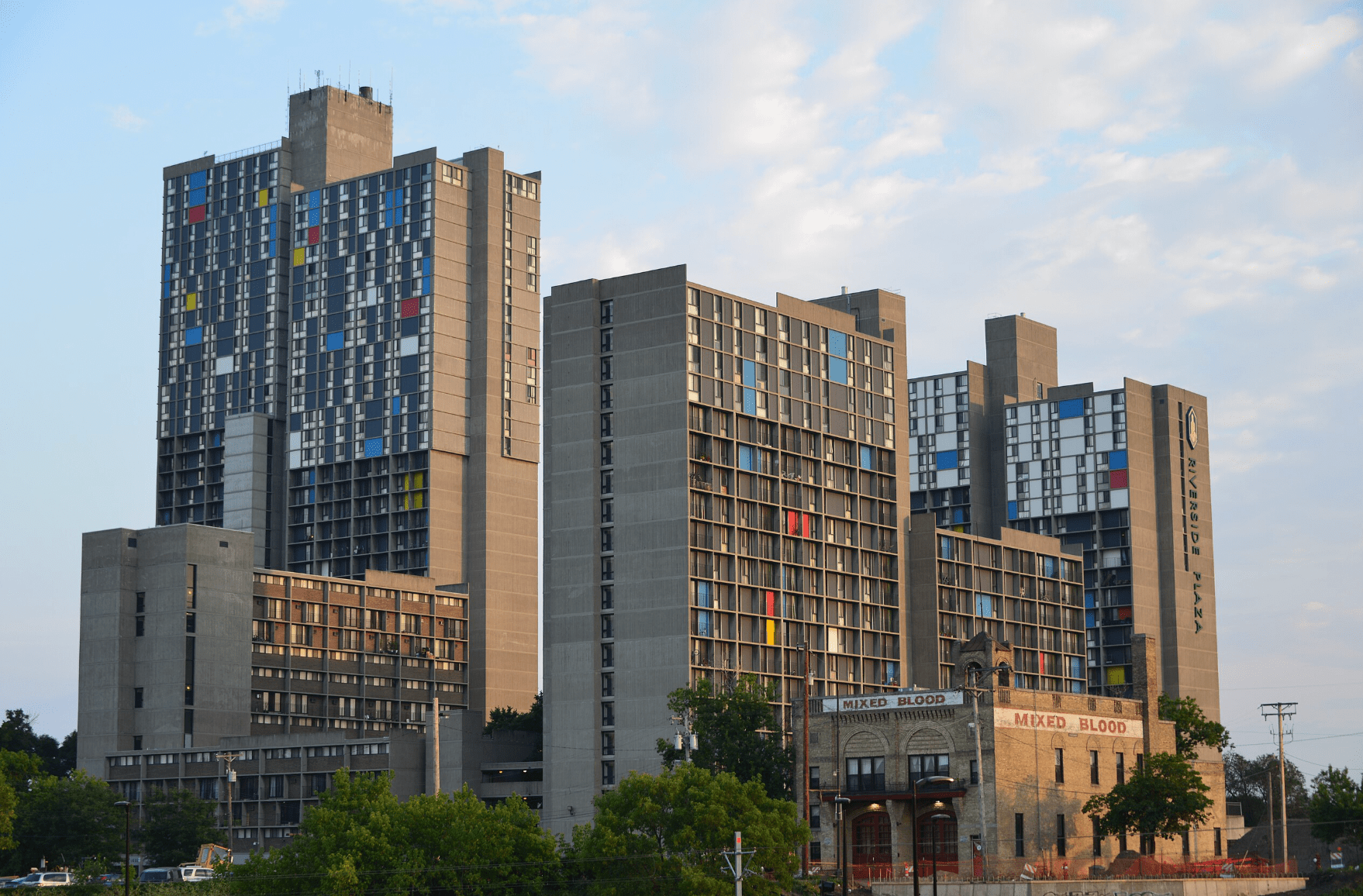

At the Fine Line Wednesday night, buzzy young California shoegaze group julie performed in front of a motley wall of vintage amps and cabinets, including one especially spectral head.

It was a Fender, possibly a Bandmaster or Dual Showman with its grille cloth and front baffle missing, allowing you to see inside it—straight through it, in fact—all skeletal-like, tubes hanging upside down within like bats in a cave, its red jewel light staring through the fog and stage-light flicker like a low-tech HAL 9000.

This striking amp was appropriate set-dressing for a band whose entire presentation exudes a humming, prickly menace—and whose music revives so many tricks from indie rock’s history. We’re talking: unsettling collages and doodles for album art, darkly surreal song titles in grammarian-goading lowercase, scant band photos, and a bassist whose stage fashion sense is very “cursed doll.” Julie took the stage to a rising and ominous electronic drone and played in front of crumpled white curtain that looked smeared with paint, onto which wispy forms were projected.

“Shoegaze,” the undescriptively named flavor of pummeling yet swooning guitar rock that originally reached moderate popularity in the early ‘90s in the U.K., is going through an odd moment of visibility right now. In the indie world, seemingly every band gets called “shoegaze” or has “hints of shoegaze” in their sound, from Wednesday to Wishy to Hotline TNT to Alvvays, even if they’re just, like, kinda loud. Major labels have signed “TikTok shoegaze” acts like Wisp and Quannnic after their earliest songs went viral, creating a weird class of one-hit wonders in a niche subgenre whose original mainstream impact in the U.S. topped out at being name-dropped in interviews by more successful bands.

Somewhere in the middle, there’s julie, a band rather than a homebody solo project, a major label signing with a strikingly raw debut album, and a “shoegaze” act that often sounds more like Sonic Youth or Dinosaur Jr. than any of the genre's foundational influences, albeit with more conventionally pretty vocals (and fewer guitar solos) than either.

Julie (they don’t capitalize their name, but I’m going toat the start of sentences so I don’t go crazy) achieved early virality with their first single, “flutter,” their lo-fi sound and enigmatic visuals ginning up lots of enthusiasm. They landed on Atlantic, becoming labelmates with Charli XCX, Ed Sheeran, and Led Zeppelin reissues. Their debut album, my anti-aircraft friend, arrived in September.

Julie may be an old-fashioned buzz band, but the album shows no sign of compromise or label interference; it’s most remarkable as a slab of raw indie rock made on the dime of one of the last-standing dinosaurs of the major label era. People have been strumming behind the bridge of their Fender Jazzmasters to make ghostly metallic clangs for a long time, so it’s not a life-changer, but it sounds good while it’s on. It could have come out in any decade since the ‘80s; it would have always found an audience and would have never been particularly trendy.

There’s a bit of old-fashioned hype swirling around julie, but one question always cuts through the buzz: Are they good live? I’m pleased to report they are, and ironically, I think the album they made answers this question almost as well as seeing them—in its aforementioned rawness, my anti-aircraft friend is, like lots of hardcore albums, a classic debut-as-advertisement-for-the-show.

Julie was joined at the Fine Line by kindred spirits from the Philadelphia indie rock scene: They Are Gutting a Body of Water (aka TAGABOW) and Her New Knife. This made for a complete evening of blurry, evocative guitar music with occasional electronic accouterments.

What truly separates julie, on record and in-person, from both the Philly shoegaze scene their openers call home and from the other thread of “TikTok shoegaze” acts previously described, is their music’s tense velocity, and its emphasis on the way the three specific people in the band play together. For all julie's artsy presentation, there’s a lot of straight-up punk rock in their sound. TAGABOW tends toward dirge-like tempos, whereas julie mostly seems to slow down in order to knock you off balance by speeding up again.

Julie’s members move together, both in the sense of speeding up and slowing down and suddenly stopping together, and in the sense of unified physical motion. Bassist Alex Brady and guitarist Keyon Pourzand sway and lurch across the stage, and Dillon Lee’s drumming is almost always in tight sync with the dynamics of Brady’s bass, giving the whole band’s collective playing a sense of waves cresting and crashing, or of a rollercoaster, with frequent sternum- and tailbone-vibrating low notes signifying the sudden drop from the height of the rails.

Despite this often bulldozing sound, there’s an intimacy to how the trio's members interact on stage. Brady tends to move in close to her bandmates when she isn’t singing, and to step heavily or bob with moments of emphasis or arrival within the music. Their interplay seems to dictate the structure of the songs more than any concern for verse-chorus convention. No one in the band will dazzle you technically, and their sloppy energy is among their most compelling traits—it gives the sense that each individual player is meant to be playing this music with these people.

The crowd on the floor at the Fine Line seemed to pick up on and participate in this intimacy as well. During one between-song interlude of drone and drum improv, general admission marshaled itself into a wide enough circle to allow one person space to complete a standing backflip. During fast sections the center of the crowd would bounce or mosh, with the circle pit occasionally reopening.

TAGABOW and julie’s sets had quite a few similarities, and the bill was maybe a little too much of one thing. Neither band addressed the crowd except to thank them before leaving the stage, and both bands alternated their traditional songs with interludes—drum n’ bass-indebted electronic music for TAGABOW, and a mix of electronic drones, feedback, and frantic improvised drums for julie.

TAGABOW’s set traded off conventional band songs with electronic tracks played through the PA, one flavor and then the other almost without exception; it was clear the electronic tracks were not merely part of the band’s performance but also a time-filling measure so the guitarists could put their instruments into whatever alternate tuning the next song called for. Julie used their between-song bits to switch guitars as well, although their logistics seemed less burdensome.

Julie even gave us a dose of increasingly rare uncertainty regarding their encore. They left the stage, and only their huddled amplifier stacks remained, their red lights still staring while the sinister electronic hum that had played them on returned to the PA. The crowd was hushed with anticipation, but not calling for more. A roadie or guitar tech came out and started unplugging cables and taking guitars offstage, but the house lights never came on. I mentally placed my bet on the band not doing an encore—they’ve only got one album, and it would seem to align with their deliberate aloofness.

Then cheering started, growing into a chant of “one more song,” and finally the tech started carrying instruments back out andplugging them back in before julie returned for an encore of “stuck in a car with angels” and “through your window,” and a final, warm thank you to the openers and the crowd. A band who plays encores for the fans—alas, maybe julie aren’t so mysterious after all.

Setlist

lochness

catalogue

pg.4 a picture of three hedges

very little effort

tenebrist

april’s-bloom

knob

clairbourne practice

thread, stitch

flutter

skipping tiles

feminine adornments

ill cook my own meals

piano instrumental

Encore

stuck in a car with angels

through your window