Wild Mind Artisan Ales hasn’t stopped growing in the six years since Jason Sandquist and his partners turned an old car wash in a sleepy Minneapolis neighborhood into one of the state’s most exciting, expansive breweries.

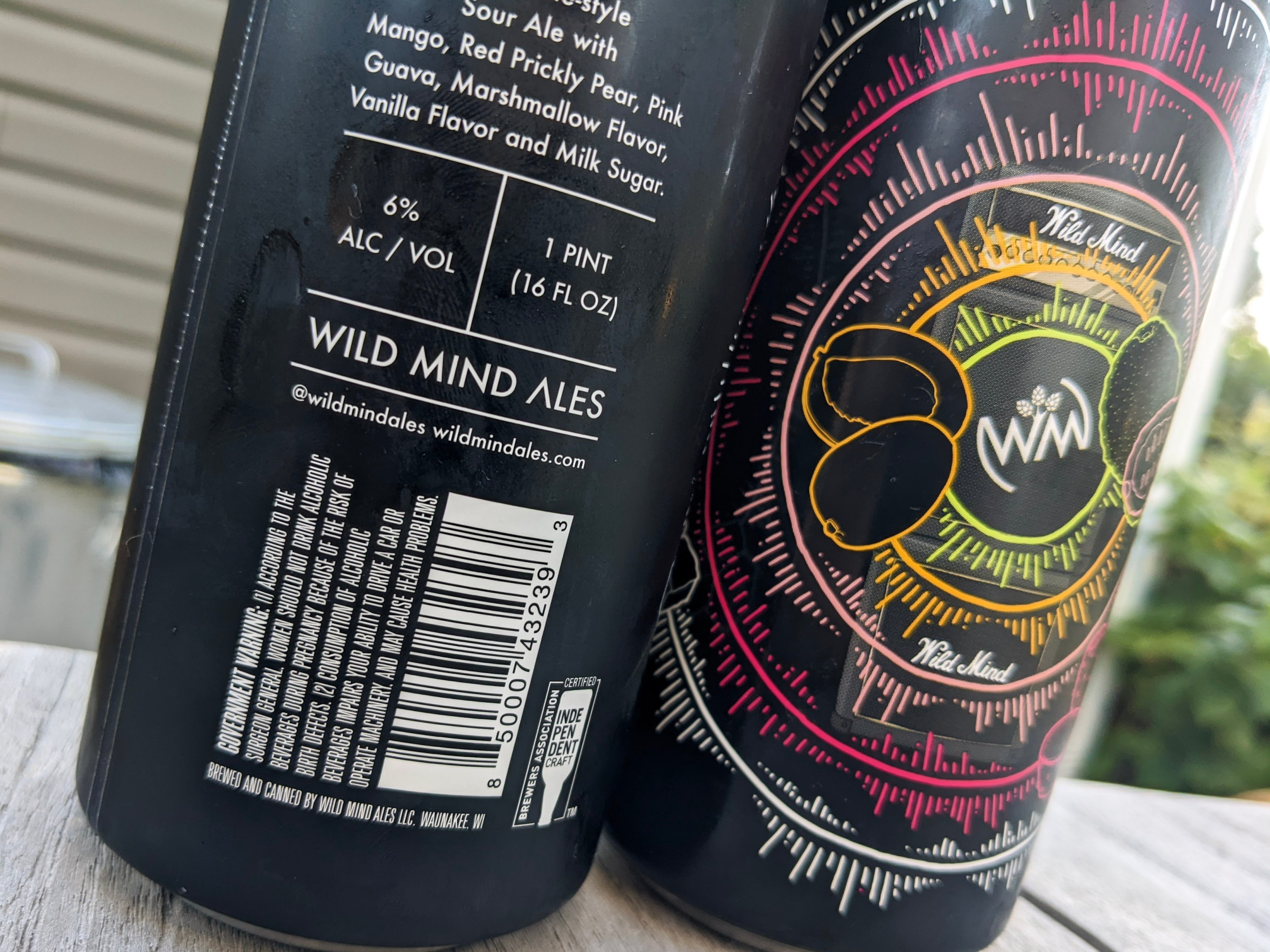

Things blew up in more ways than one. In 2018, the partners endured a messy breakup with their founding brewer, and that same year, Wild Minds won City Pages Best Brewery. They rebranded, throwing away the “Artisan” in their name, and opened a coffee shop. But the biggest change in their history is nearly imperceptible, written in fine lettering on the back of their 16 oz. cans just below the barcode:

BREWED AND CANNED BY WILD MIND ALES LLC., WAUNAKEE, WI.

Spend enough time at the liquor store poring over beer labels, and you’ll see the name “Waunakee” pop up more and more on the labels of beers ostensibly “brewed” by Minnesota breweries. Located 30 minutes outside Madison, the 15,000-person village has quietly woven itself into Minnesota beer tradition—so much so that when Yoerg Beer, the historic first beer ever brewed in Minnesota, was resurrected in 2016, it was billed from Waunakee.

Seeing a Wisconsin town on a Minnesota beer might seem like heresy, but printing “Waunakee” on labels across the country has been Isaac Showaki’s vision since he founded Octopi Brewing in 2015. Showaki opened the doors to Octopi after 16 years in consumer packaged goods, first as a consultant with Heineken in Panama and later as a partner in Chicago’s 5 Rabbit Cervecería. While at 5 Rabbit, Showaki tried out several contract brewers as a way to get his beer onto liquor store shelves. But he was soon frustrated with his partners, who he says treated his business like a burden.

“There wasn’t a really good copacker in the area, the quality just sucked, and no one took it seriously,” Showaki says. “Capability sucked, flexibility sucked, pricing sucked, everything was just a nightmare. I was brewing in eight different places in less than a year, from 10 barrels all the way up to 300 barrels at a time. I was not happy with anybody.”

When the 5 Rabbit relationship soured, Showaki sold his shares in the brewery and decided to found a company that would gladly take on brewing contracts. Octopi does carry a line of their own brews, which you can taste at the Waunakee taproom, but Showaki quickly turned his focus to bringing in well-regarded Midwestern brands like One Barrel Brewing, Eagle Park Brewing, MobCraft, Forager Brewing, and Funk Factory Geuzeria, enticing them with a state-of-the-art facility that guaranteed unyielding quality at a much higher volume than they could produce alone.

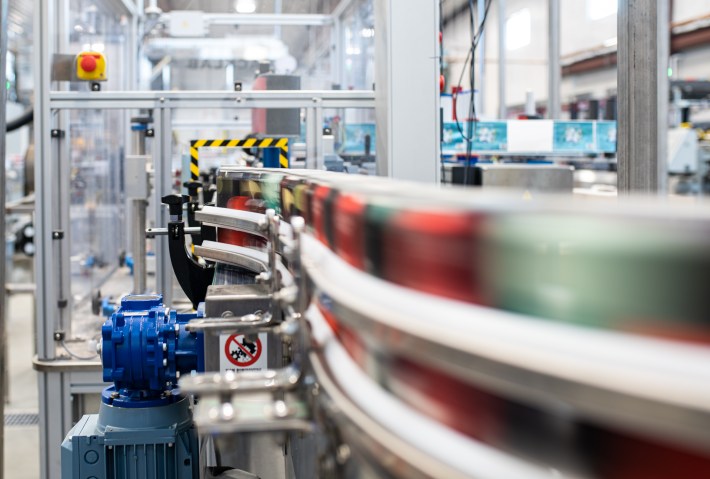

The gambit worked. From 2015-2020, Octopi grew 100% year over year, making it one of the fastest-growing businesses in the Midwest. Their portfolio now includes roughly 17 beer brands, most of which are kept secret due to industry-standard NDAs. To produce these beers, they recruited high-level brewers to run their craft beer portfolio; former New Glarus and Goose Island brewer Jared Jankoski became their brewmaster in 2019.

Octopi does more than copackage beer—they launch brands, provide quality assurance, broker deals on raw ingredients and packaging materials, and create relationships with distributors. They even make house beers for Aldi and Trader Joe’s. In 2021, they broke ground on a $72 million expansion, which, when finished, will bring their total capacity up to one million barrels, putting them on par with the likes of Boston Beer Co. and Sierra Nevada among the largest beverage producers in the country.

“I would love to be the best midsize copacker in the U.S. That's my goal,” Showaki says. “My original business plan said 50,000 barrels. That was my max goal. The fact that we're even talking about a million is beyond my wildest dreams and imagination.”

Craft Beer’s Open Secret

Sandquist had his eye on Octopi for two years before Showaki could take on Wild Mind’s beer. He’d identified the Waunakee facility as a way to scale up his small neighborhood brand, but with so much expansion and the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, he couldn’t get in the door. Wild Mind did two collaborations with Untitled Art, the high-concept, style-bending company Showaki started with Levi Funk of Funk Factory, but that’s as close as he could get until 2020, when they finally signed a three-year contract.

Thanks to Octopi, Wild Mind is now in 27 states, as well as Canada, Europe, Australia, and soon, Asia. They even bought their food truck, now a permanent feature of the brewery, off Showaki. Wild Mind uses Waunakee-based Pequod Distributing, one of Octopi’s preferred partners, for their business outside of Minnesota, and it’s Octopi’s stellar reputation with beer wholesalers that helps them get that widespread business. According to Sandquist, if a distributor knows you’re made at Octopi, they’ll grab your beer on a pallet mixed with other customers, no questions asked.

“We went from making 10 barrels of beer a batch at our brewhouse to doing 100 barrels at a time,” Sandquist says. “We're riding the coattails of Octopi and Untitled Art, because [distributors are] picking up pallets with a lot of different beer from a lot of different breweries all at once.”

Contract brewing is nothing new to Minnesota: Brands like Hamm’s and Schmidt have been traded around to several different facilities, many outside of the state, and mainstays like Summit and Schell’s have devoted capacity to contracts over the years. Minnesota’s Cold Spring Brewing Co. has operated as one of the most well-known contract breweries in the Midwest since 1874.

But Cold Spring and other industrial-scale breweries developed a reputation for making cheap runoff beer. They were hard to work with, often forcing breweries to reformulate using lower-grade ingredients. When the American craft beer wave started in the late 1970s, brewers set themselves apart from the pack by focusing on small-batch, locally made beer.

“[Contract brewing] got some of the stigma in that era from some of the other craft brewers who were trying to do it the ‘pure’ way and trying to get their own brewery started,” explains Minnesota-based beer historian Doug Hoverson, author of Land of Amber Waters: The History of Brewing in Minnesota. “Contract brewing was kind of cheating. You were able to get beer on the market, but you haven't suffered through getting your brewery going and you haven't suffered through waiting on equipment and permits. You are just selling beer.”

It all came to a head in 1996, when NBC’s Dateline ran an exposé on Samuel Adams, attempting to damn the company for producing the majority of its beer in Pennsylvania and New York. Co-founder Jim Koch was nonplussed by the accusations, dropping a quote that’s lived on as one of the most enduring challenges to the mythology of early craft beer: “If Julia Child comes to your house, brings her own ingredients and her own recipe, and makes dinner for you, who made dinner, you or Julia Child?”

In the decades after, contract brewing became a way for breweries to get to market quick and establish a flagship. Some of Minnesota’s best-known breweries started as contractors in the 2010s. Fulton, Pryes, Lake Monster, Finnegan’s, and Lift Bridge all followed this route a decade ago, building popular taprooms after getting a foothold through contracting, but Hoverson doubts this is a viable route anymore. The consensus is that modern craft drinkers want to drink straight from the source, bellying up across the bar from where the beer is made. But Octopi (and other contract facilities of its ilk, like Florida’s Brew Hub) are dismantling conventional wisdom with the success they deliver. For Sandquist, contracting is just good business sense.

“People used to argue that contracting means you just don't have as much skin in the game,” he says. “And I'm like, ‘Please explain?’ I have a $2 million brewery, that's a lot of skin in the game. But before I take the next step and maybe go lease 50,000 square feet of space, I want to know if there's proof of product in the market first.”

A Humble Arrangement

Because Forager Brewery in Rochester is a brewpub, they’re not allowed to distribute beer like a normal brewery. Minnesota statutes forbid them from packaging in 12- and 16-oz. cans, and they can only sell 750 barrels in off-sale beer per year.

But that didn’t stop restaurants and liquor stores from asking co-founder Austin Jevne to carry his beer. Forager’s reputation in the Minnesota beer world is top-class; Beer Advocate rates their Nillerzzzzz imperial stout the best beer made in the state. Their releases often see lines around the corner, and crowlers sell for several times the sticker price on the secondary market. The buzz was too strong, too sustained to keep the beer in Forager’s 3.5-barrel facility, so Jevne decided to break the paradigm.

In 2019, he founded Humble Forager, a Forager offshoot with the opposite business strategy: no taproom, just beer brewed exclusively for liquor store distribution at Octopi in Waunakee.

“With Octopi, I can run the business and be creative about recipes and ingredient sourcing and branding, design, and I didn't have to focus a huge piece of effort on the actual licensing and each state,” Jevne explains. “I didn't have to rent a separate warehouse to store my product and have a warehouse team of people who are packing pallets. It's a one-stop-shop.”

Humble Forager has been a roaring success, attaining similar Untappd and Beer Advocate scores as the original Rochester brewpub in a fraction of the time. Beers like Barrel-Aged Existential Joy and the Coastal Sunshine sour line have surpassed Forager standbys in terms of reputation, all without any thought to the locality or craft ethos of the beer.

“Isaac is definitely a visionary,” Jevne says. “Isaac knew where the industry was heading and was willing to take those risks and investments for his brand to really focus on working with new up-and-coming breweries.”

Jevne prizes Octopi for their willingness to take on complicated beers, like pastry stouts with lots of adjuncts and slushie-style sours that need to be carefully pasteurized to be shelf stable. They also have a vacuum separator in house, which means Octopi can produce nonalcoholic beer and hard seltzer base in a single brew. Having access to the machine allowed Jevne to launch the Humble Bumble seltzer line without investing a quarter-million dollars in machinery.

“You're starting to see products come out of some of these contract facilities that are [better than those] produced in local breweries around the country,” Jevne says. “When I first started giving Octopi my recipes, Issac would say, ‘On a scale from one to 10—one being the easiest beer recipe that you possibly could produce, and 10 being pretty much impossible—almost all of your beers are nines for us.’ And I'm like, ‘Well, that's why I'm contracted with you, because you are willing to take on that challenge.’”

While Humble Forager is brewed predominantly at Octopi, Jevne also contracts brews at Fair State’s St. Paul facility. But he’s not looking to move into a new, larger facility of his own any time soon. He’ll keep Forager as the Minnesota brand of the business, and for the time being, “My intent is to grow with Octopi and see how that works,” he says.

“Austin is one of the clients that really pushes the limits of what we can do at scale,” Showaki says. “You can’t have the best team and not have the best equipment, right? We’ve really been investing in both since the beginning, and it’s been great to also partner with the right brands that really have the potential to grow.”

Jevne recognizes that contracting means they’re compromising some of the local-made bona fides of craft beer, but he also recognizes that appeal really only motivates a small subset of drinkers. In a world where some craft breweries are making a name for exploding sours, working with Octopi allows Jevne to stand above all while producing at a high volume without compromising on quality.

“I would love for people to take a beer from Octopi that I produce versus a beer produced in a small local brewery and see which can tastes better in a year,” Jevne says. “It feels great to go to your local brewery and shake hands with the person who's making the beer. In people's minds, that makes a product be perceived as higher quality. But that doesn't mean it's better.”

The recent changes to Minnesota beer laws mean breweries will soon be able to package their own beer and sell it out the taproom. That beer must be produced in-house, so Octopi will miss out on that business, and as their clients buy their own canning machines (Sandquist says Wild Mind got a new canner of their own in July), that may take the name “Waunakee” off the labels of some Minnesota beer. Beyond that, according to local beer lawyer Jeff O’Brien, Minnesota breweries had been using contract brewing to keep their barrelage low enough to legally sell beer in their taprooms. With the so-called “growler cap” going up, they can now produce that volume in house without the markup of using a co-packer.

But Showaki isn’t concerned. The role of contracting has morphed so much over American beer history that he’s prepared to take on the next wave. Only 20% of his business is beer, anyway. The rest of Octopi’s tanks go to making seltzer, cider, ready-to-drink cocktails, CBD elixirs, soda, and other beverages. When breweries are ready to move into that direction, he’ll be there, as adaptable as the eight-legged creature that he named his company after.

“Eight tentacles means we can do eight things at a time,” Showaki says, adding that his wife, Marissa, came up with the name Octopi. “It's underwater, in constant motion; it's an invertebrate, so it can change speeds really fast. And it uses camouflage, so we can do it behind the scenes.”