The following is an excerpt from Nature’s Crossroads: The Twin Cities and Greater Minnesota, a first-of-its-kind anthology from environmental historians Chris Wells (Macalester College) and George Vrtis (Carleton College).

“We learned that the relationships between the Twin Cities and the rest of the state are incredibly powerful and reveal an extraordinary degree of environmental and cultural complexity," says Wells, who co-edited the project alongside Vrtis. "This extends to things like wheat and timber, which were cornerstones of the early Minnesota economy, but it also helps explain less obvious things, like the urge to head up north to the cabin and the complicated politics of the Iron Range.”

In the chapter below, "Follow the Arrows to the Arrowhead: The Environment of Tourism in the Interwar Years," writer Aaron Shapiro explores "the transformation of northern Minnesota from a landscape of stumplands and failed farms into a mecca for nature tourism." He discovers that "Up North" culture has "deep roots with surprising intentionality behind it," and details decades of deliberate campaigning by the state to turn the Arrowhead region into an economic engine fueled by outdoors-loving vacationers.

You can buy the book, which was published earlier this month via University of Pittsburgh Press, here. Enjoy!

Arriving in northern Minnesota in 1886, Joseph Ruttger worked in the woods, met his wife, and settled on an island in Deer Lake. Hearing reports of good food and fishing at the Ruttgers', railroad travelers arrived to inspect their veracity in the 1890s. As business grew, the Ruttgers added cottages, charging $5 a week for bed, board, and boat. Joseph Ruttger moved from hauling timber to enticing tourists. Wilson Dunn arrived in Minnesota from Wisconsin in the 1880s, purchasing lakefront land north of Pelican Rapids and building a resort that attracted hunters, fishermen, and families from the Twin Cities.

By 1929 Wilson’s son, Roy, expanded the resort to include two dozen cabins and a main lodge. He also served in the Minnesota House in St. Paul, rising to majority leader, and returned to operate the resort during summers. Facing a declining timber industry and agricultural failures, Ruttger and Dunn were among the many early operators who joined tourists, residents, and the state to make the vacation landscape in Minnesota’s North Woods, and in the process helped make “up at the lake” and “up north” common refrains for Twin Cities residents.

While geology and history mark time “up north,” natural features took on new meaning in an expanding consumer society as vacationers from the Twin Cities and beyond enjoyed northern Minnesota’s tourist camps, cabins, resorts, state parks, and national forests during the interwar years. The market’s intrusion into the 19th-century countryside established urban-rural connections that exploited natural resources, altered lives, and transformed the landscape. By promoting vacations as a consumer item that improved health and productivity while providing an escape to a supposedly more natural environment, 20th-century advocates hoped tourism could diversify the economy and address land-use concerns. Like earlier lumbermen, they also saw profit in nature. But unlike lumbermen, who cut and ran after felling the forest, they relied on nature’s regenerative forces to provide a new cash crop, a forested and lake-dotted countryside offering outdoor recreation for the masses.

Experiencing deindustrialization earlier than the Rust Belt cities to which it sent natural resources, Minnesota’s North Woods residents participated in transforming a landscape of production into one of consumption. Familiar with the boom-and-bust cycles of extractive industries directed by outside capital, they wanted a more secure future. A growing market of vacationers boosted such aspirations. Promoted and experienced as a haven from the industrial world despite the North Woods’ intimate connection to it, vacationing offered a respite in the place that had provided resources to build cities.

But this time, the consumers—tourists—traveled to enjoy the landscape rather than having its resources extracted and shipped to them. The ascription of aesthetic values on natural places commodified nature in new ways, as Minnesotans realized consuming nature for pleasure demanded new approaches to managing natural resources. Vacationing with family at a rustic cabin, embarking on mental journeys by reading the Work Progress Administration (WPA) guide to Minnesota’s Arrowhead Country, enjoying summer camp near Bemidji, and hiking trails constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) in the Superior National Forest, they redefined nature in consumer terms through leisure.

Although scenic beauty helped make the region a destination, tourism is not a natural product, but rather is managed and packaged by people and organizations with often competing interests. Tourism in the North Woods had its own distinctive character. Historian Hal Rothman characterized western tourism as a devil’s bargain because it provided economic benefits but vested power with outsiders and contributed to a loss of the uniqueness that made places worth visiting. North Woods tourism attracted nonresident interest and altered the landscape, but residents exerted greater control and experienced tourism as less of a devil’s bargain than their western counterparts. Local and state activities to develop tourism and manage land use presaged federal efforts, revealing the roots of New Deal conservation and land-use planning. Nationally, rural land-use policies emerged within an urban industrial society, and conservation efforts were increasingly connected to urban consumer needs, from early 20th-century fights over water in California’s Hetch Hetchy and Owens River valleys to growing urban desires to enjoy leisure in nature. Ultimately, the activity of local residents cooperating with and contesting conservation regulations proved crucial in making northern Minnesota a vacation destination.

Government facilitated tourist development—through promotion, conservation, and construction—and thereby became a tourist industry stakeholder. The creation of the U.S. Forest Service in 1905 and the National Park Service in 1916 led states to establish more parks and forests for conservation and recreation. Minnesota played a pioneering role, creating Itasca State Park at the Mississippi River’s headwaters in 1891. While many rural residents expressed concerns about interference in local affairs, they participated in consumer culture on their own terms. As the preeminent symbol of that culture, the automobile gave a boost to tourism, democratizing travel and increasing access to the North Woods. Working within the region’s environmental benefits and constraints, state and private interests looked to tourism to diversify a region suffering from industrial decline and an inability to farm northern lands. Fueled by the region’s engagement with a modern consumer culture in which changing technologies and expanding market relationships transformed land, labor, and leisure, creating the North Woods involved organizational leadership, new land-use policies, and effective development and promotion.

Cultivating a Landscape of Tourism

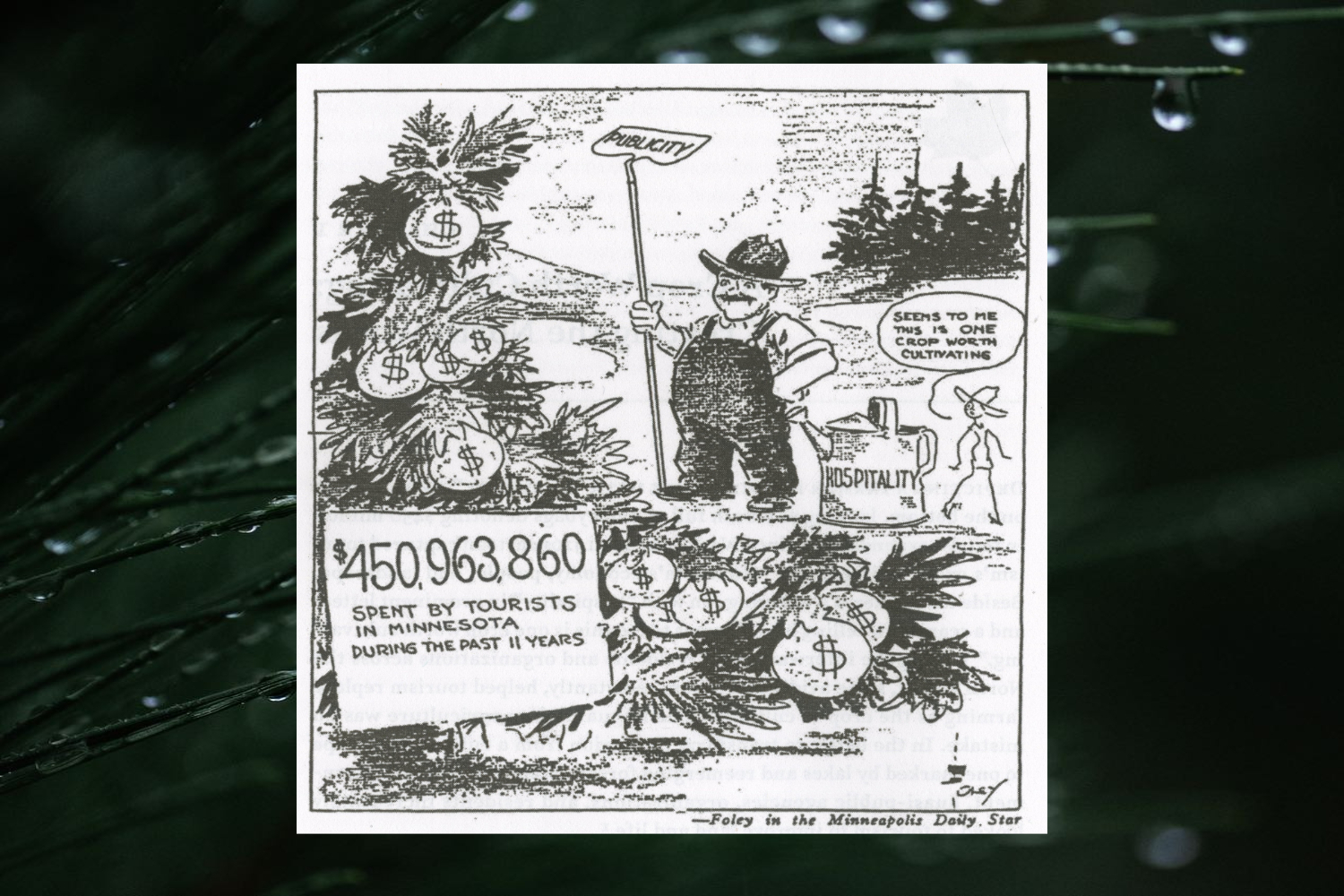

Depicting a farmer holding a hoe with “publicity” emblazoned on the bottom, looking at a bush full of moneybags denoting $450 million in tourist expenditures since World War I, a 1920s Minneapolis Daily Star cartoon, featured above, captured tourism’s impact on Minnesota’s economy, people, and landscape. Beside the farmer stood a watering can with “hospitality” in prominent letters and a scarecrow telling him, “Seems to Me This is One Crop Worth Cultivating.” Government agencies, regional organizations, and residents, some avidly and others reluctantly, helped tourism replace farming as the crop to cultivate. The lingual link to agriculture was no mistake. In transforming a cutover land- scape to one marked by lakes and reemerging forests, they looked to tourism to improve land and life.

In the late 19th century the state recruited farmers to northern lands. Upon arrival, individuals discovered stump-filled lands and tilled rocky soil with hopes of farming. After decades of unsuccessful efforts, organizations like the Minnesota Arrowhead Association (MAA) emerged, working with state government to develop tourism. The area did not initially offer an aesthetically pleasing landscape, so advocates supported a program of reimagining it, conserving and even reconstituting its natural scenery in order to sell its charms to urban dwellers. Often promoted as untouched and natural, the reality was that the land had long experienced the imprint of human hands.

Rather than rely solely on private efforts, in 1918 Minnesota appropriated funds for tourist promotion and development, a decade before Michigan and nearly two decades before Wisconsin. In language highlighting tourism as a cash crop, the St. Paul Pioneer Press suggested the state was now “officially interested in the exploitation of its natural scenic resources.” It declared Minnesota had not fully capitalized on these assets, viewing tourism as a benign land use. Inquiries poured into the state, including many echoing the sentiments of Des Moines resident Charles Parker, who labeled Minnesota “the most wonderful summer resort state in America.” Initially hoping people would come to Minnesota as tourists and then settle, by 1923, with tourists depositing money in state and local coffers, state agencies in St. Paul viewed tourism as a solid industry in its own right.

Organizations like Mathias Koll’s Northern Minnesota Development Association (NMDA) backed state efforts. Limited farming opportunities led the NMDA to advance a conservation agenda emphasizing “preservation and propagation of fish in our Ten Thousand Lakes; creating in the pure cool waters of this state a continuing industry and one of growing recreational and commercial importance.” Like earlier agricultural advocates, Koll initially viewed tourists as potential settlers. He ultimately encouraged the state to promote attractions, suggesting that tourists helped local businesses and provided a market for farm products. The State Immigration Board also promoted northern Minnesota, assuring vacationers of abundant fishing, hunting, and lodging options in Minnesota’s lake-dotted north while obscuring mining’s and tourism’s impacts on the land.

The MAA, NMDA, and the state were not alone in believing tourism could offer employment, return abandoned land to tax rolls, and diversify the economy. Federal agencies aided local efforts by providing recreation on public lands. Minnesota benefited from having national forests earlier than Wisconsin and Michigan, positioning the state as a regional tourism leader. While Minnesota (now Chippewa) and Superior National Forests were initially established for timber and watershed protection, the U.S. Forest Service faced growing competition for the recreational dollar, as well as its lands, from the National Park Service. The Forest Service’s Term Permit Act allowed cottage construction in national forests and extended leases for up to 30 years, starting at $10 annually, with renewal options. Promoting remoteness while also noting that cars spurred tourist access to the Superior, the agency proposed, “The lake region north of Grand Marais will no doubt be a mecca for people in search of ideal summer-home sites upon the completion of the automobile road now being built into that region.” The presence of two national forests along with agency interest in recreation helped develop the tourist trade.

During the 1920s tourism transformed northern Minnesota’s physical and economic landscape. Resorts grew from a few hundred to nearly 1,400 as roads opened previously inaccessible areas. Like other advocates, the MAA initially hoped tourists would settle and become producers for a new industrial economy, commenting on the “proper type of tourists, attracted first for pleasure and later, for permanency.” But the MAA quickly realized tourism was tied to transience rather than permanence, so the goal became attracting tourists as consumers who contributed to the local economy. It drew institutional members from area towns, encouraged reforestation and new roads, promoted vacations, and received inquiries. In 1926 the MAA conducted a naming contest for the organization, which had been known as the Northeast Minnesota Civic and Commerce Association. Pittsburgh’s Odin MacCrickart, who coined the Arrowhead term because the region’s boundaries appeared as such, emerged as the winner among 30,000 entries.

The Arrowhead name stuck, broadcasting a sense of adventure. Promoters also reminded North Woods vacationers of the pine-scented air, cool summer breezes, lakes teeming with fish, and woods filled with wildlife. But the escape was not complete. Vacationers were immersed within a web of actors that regulated the experience and influenced how and where they vacationed. In 1931 Minnesota established a Tourist Bureau in the Department of Conservation to oversee promotional campaigns and assist regional organizations. The Highway Department addressed infrastructure and scenic roads while the Planning Board hoped to create jobs by attracting urban tourists.

New Deal programs built on these earlier efforts to develop public recreational lands. Federal funds for roads, conservation, and the WPA American Guides promoted travel as a means to unity, recovery, and nation building. At a fundamental level these programs offered work during the Depression. But they also provided people with a new understanding of the nation’s landscape and people. Minnesota’s state and Arrowhead guides reinforced the image of far northeastern Minnesota as a wilderness, with Superior National Forest offering 15 canoe trips. Readers of Minnesota’s guides discovered a place filled with outdoor adventure and learned about the region’s industrial history. In 1940 Governor Harold Stassen encouraged visitors to enjoy Minnesota’s outdoor opportunities amid natural beauty, where residents offered cordial service and lodging while the state ensured a safe and pleasant experience.

Preserving Nature for Tourists

As urbanization proceeded apace, the idea of preserving natural resources emerged more forcefully among wilderness advocates, government officials, and North Woods residents. Born in Chicago and raised in northern Wisconsin, Sigurd Olson called northern Minnesota home starting in the 1920s. As a naturalist, writer, and educator, Olson viewed wilderness as both physical place and ideological concept. Olson, who operated a canoe outfitting and guide service, saw wilderness as an escape from the urban order. But that order clearly prescribed the ways people experienced and thought about wilderness. Guides still worked for vacationers, providing information on fishing spots and maneuvering through the landscape in exchange for payment.

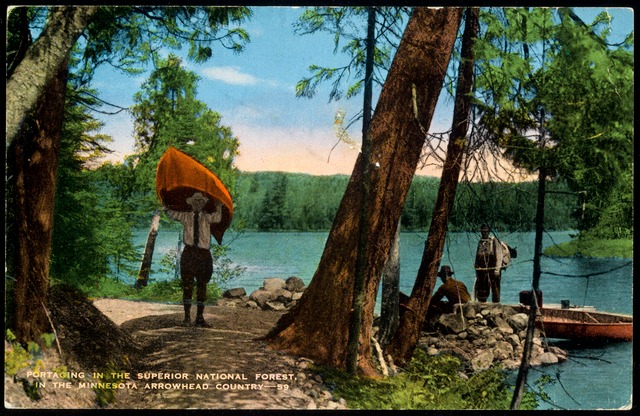

Justifying designating portions of Minnesota’s Superior National Forest as roadless, Olson championed preservation. He wanted people to experience it as voyageurs had. “Nowhere else can such beautiful lakes be found,” he wrote in 1929. “Nowhere else can you find them close together enough to make what is known as a canoe country, and nowhere else is there so much beauty concentrated in one spot as here. It is the last area of its kind in the country. Are we going to sacrifice it to the ogre of commercialism?” Olson joined other regional voices that saw spiritual and financial benefits in wilderness tourism.

The U.S. Forest Service initially considered recreation a lesser use than timber production but with automobile touring increasing demand, it responded by providing recreational opportunities. In 1918 landscape architect Frank Waugh’s report declared recreational forest use equal to that of timber, grazing, and watershed protection. Noting its “substantial commercial value” of $7.5 million annually, he encouraged the agency to further develop recreation. The Forest Service’s first landscape architect, Arthur Carhart, crafted plans for Superior National Forest that called for maintaining the area’s pristine nature while providing easier access with backcountry lodges and marked canoe routes.

Ernest Oberholtzer joined Olson, Waugh, and Carhart in battles over Minnesota’s Boundary Waters. In 1927 Oberholtzer established the Quetico-Superior Council, whose conservation program brought together American and Canadian interests. Attacking industrialist Edward Backus’s plan to build dams that would flood several thousand miles of international shoreline, Oberholtzer expressed outrage that private greed could destroy such a unique wilderness resource. He called for federal intervention to stop Backus, opining that “no conceivable benefits from such a plan can justify the wholesale impairment of public values in so large and so unique an area.” Backing came from the local Arrowhead Sportsmen’s Association (ASA), which sought to protect its members’ ability to hunt and fish; tourist entrepreneurs like Wilderness Outfitters owner Joe Pluth; as well as the Ely Commercial Club, a group of businesspeople convinced Backus’s plan would harm Ely’s economy.

To preserve scenic, recreational, and inspirational values, Oberholtzer advocated public control of the region’s wilderness. Not simply a case of outsiders-as-preservationists versus residents-as-resource-users, the struggle over roads and Backus’s dams saw local commercial clubs join sportsmen and wilderness advocates in fighting industrial expansion and landscape despoliation. Perhaps the most prominent of these sportsmen’s groups was the Izaak Walton League, established in 1922 in Chicago. In April 1923 League president Will Dilg appeared at a Duluth public hearing, testifying that the Forest Service should abandon its road plans and telling those assembled, “Only God could make that forest and only man can destroy it. It must be preserved as wilderness for future generations of young Americans, and none of us have the moral right to destroy it as such.”

An Izaak Walton League Monthly article reported that Dilg helped convince the Forest Service “that the biggest word in the Superior Forest dictionary is ‘National’—that it is bigger than the forest itself.” The League’s local Arrowhead chapter added its voice, fighting Forest Service road projects and pro-road interests hoping for “A Road to Every Lake.” Vast road plans were ultimately defeated in 1926 when the Forest Service set aside three roadless areas. As a local organization, the chapter supported policies preserving fish and game for sport and suggested tourism offered possibilities for residents that other industries did not. Managed accordingly, it believed the region’s “woods, waters, and wild life are not only its rarest distinction but promise to become its richest asset.”

As citizens advocated conservation policies aiding recreational development, Forest Service officials linked tourism and reforestation. Arthur Carhart’s recreational survey of Superior National Forest conceived of the region’s wilderness in terms of scenery and access. He did not exclude timber cutting, but noted that in some locations, particularly shorelines, “the aesthetic qualities shall, where of high merit, take precedence over the commercialization of such timber stands.” Looking to balance forest uses, Carhart offered a compromise premised on the notion that scenic values were, in certain places, the most valuable and must be preserved. His vision was not of a wilderness devoid of all other uses, but a recreational outlet in a forest guided by sound conservation principles. Carhart believed agency emphasis on timber production overshadowed his recommendations. Reflecting later on the importance of regional actors in spurring policy changes and vindicated by plans for Superior National Forest that drew on his endorsement of its recreation potential, he remarked, “I think we all know that the Forest Service was not ready to take a progressive, intelligent attitude toward the Superior and recreation until the people in Minnesota and the Middle West rather kicked them in the ribs.” Local fears about losing control and access took root in diverse situations: against Backus’s dam projects, over Forest Service policies in the Boundary Waters, and among those who opposed proposals to establish a national park.

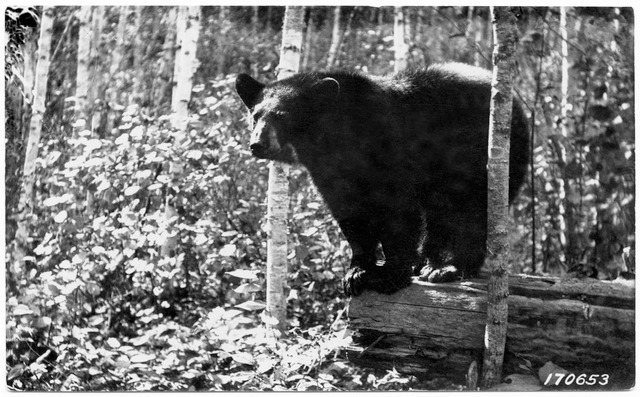

The Arrowhead Sportsmen’s Association objected to a potential national park in the Superior National Forest, fearing it would make the area off limits to hunting and fishing. While the ASA rallied against the park proposal, Forest Service officials advanced forest recreation. Carhart believed “Ely has the opportunity of becoming a tourist town.” He suggested crowds could be handled without destroying recreational, wildlife, and forest values cherished by locals. Many Ely residents heard Carhart’s call and catered to the growing tourist trade. These operators contributed to conservation debates since business depended on their clients accessing public lands. The development of recreational facilities on public lands also brought government further into the tourist arena. State policies for fostering abundant fish and game dovetailed with promoters who viewed the outdoors as a commodity and knew selling retreats depended on having fish to catch and forests filled with wildlife. Despite their diverging views, government officials, wilderness advocates, local citizens, and sportsmen’s associations brought new approaches to land-use issues that helped establish Minnesota’s North Woods.

Automobile access, lodging improvements, and the desire to escape cities during summer all contributed to a new vacation landscape. Helen Beebe of Minneapolis, who worked for Dayton’s department store, wrote resort operator Roy Dunn about wanting to escape to the outdoors, explaining, “I am cooped up in a room the year round and when I am on vacation I want a change.” Other guests had different motives, including fraternities using Dunn’s for social functions and fishermen looking to catch walleye. Still others viewed the resort as a place for family vacations. Leslie Setzer, an employee at St. Paul’s West Publishing Co., inquired about accommodations and a ride from the Detroit Lakes train station for her and a friend. Guests came as individuals, families, and groups seeking refreshment and entertainment among Minnesota’s northern lakes and woods.

Vacationers also arrived to canoe in Superior National Forest. The Ely Commercial Club recommended outfitters and guides while Lake Vermilion resorts provided a location map. But who were commercial clubs and resort owners trying to attract? One group was clear, with one publication focusing on “the tired business man who must periodically get away from the rush and noise of the city and build up a run down and worn out body.” The tired businessman was a potential client but as guest lists, letters, bulletins, and registers suggest, so were sportsmen, single women, families, and students. Resorts explored many avenues to reach these vacationers. Roy Dunn contracted with Chicago’s Curt Teich and Company, to create postcards for his resort. Dunn also worked with his legislative colleagues in hopes of garnering official business.

The New Economic Landscape of the North Woods

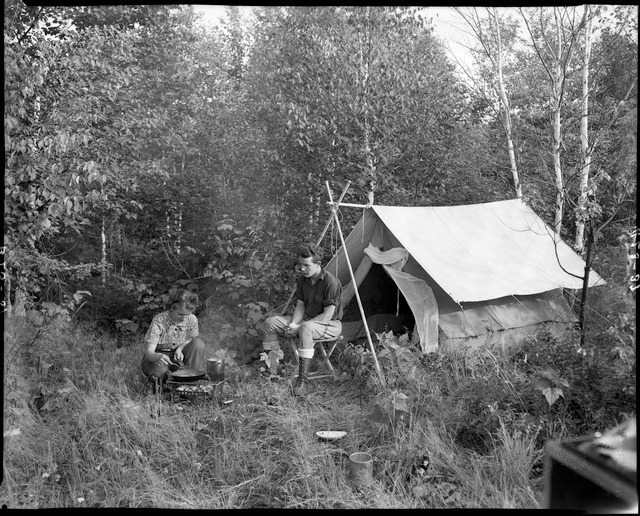

While the Boundary Waters and the Gunflint Trail offered wilderness experiences, other operators joined the Ruttgers in providing for vacationers in Minnesota’s Brainerd Lakes area, where nearly 300 resorts marketed it as “Va-Ka-Shun Land” in 1929. Resorts and lodges were one element of the lodging landscape. By the 1930s housekeeping cabins offered simple places to stop for a night and an economical alternative for longer vacations where guests cooked and cleaned for themselves. Tourist camps, state parks, and national forests provided camping at minimal expense.

While conversing with guests at their northern Wisconsin lodge, Dora Blankenburg and her son Russell discovered that some were heading to Minnesota’s Arrowhead to enjoy Lake Superior’s North Shore and canoe the Boundary Waters. Others explored mining history, while boosters promoted curative properties among pine-scented air. Whether one sought health, adventure, or history, northern Minnesota offered opportunities for vacationers and potential resort operators. Russell visited Minnesota and bought land to establish Gunflint Lodge in 1925. After operating both places, the Blankenburgs sold Gunflint Lodge to the Spunners, friends who advised them on their Wisconsin resort purchase. Mae Spunner brought her daughter Justine to negotiate terms. Gunflint had three guest cabins without electricity or indoor plumbing, a small lodge, dining room, and a store. Justine made improvements, enlarging the dining room and adding a lounge. These additions faced the road rather than the lake, highlighting the lodge’s orientation toward welcoming auto tourists on the Gunflint Trail.

During the Spunners’ first season in 1930, Mae planned meals and supervised staff while Justine handled administration and repaired equipment. Indian neighbors shopped at the store and worked as guides, housekeepers, and servers. In 1933 the Spunners moved to the Gunflint permanently. That summer, Bill Kerfoot arrived on the Trail, camping on Gunflint Lake’s west end. As Bill was eager for a job, Justine hired him in exchange for room and board. The following year Bill and Justine married and began operating the lodge together. Their newsletter, Gunflint Gossips, reported on lodge activities and created a sense of family among the guests. Originally male hunters and anglers came in spring, early summer, and fall. Gradually, more women and families visited.

Gunflint Lodge joined the growing array of accommodations in Minnesota’s Arrowhead. Like many who participated in constructing the tourist landscape, Bert Pfeifer entered the cabin business when he found himself living in an area drawing tourists. Born in North Dakota in 1915, Pfeifer came to work at his great-uncle’s store near Minnesota’s Itasca State Park. After marrying in 1939, Bert purchased housekeeping cabins, recalling, “No reservations. Most of them just come off the road and were just touring and looking for a place to stay.” Cabin owners valued highway rather than lake access to attract visitors. In contrast to resorts, Bert’s guests usually stayed only a night or two and included farmers wanting to fish and enjoy the state park. Bert added new cabins with running water and electricity. To make ends meet during slack times, he worked other jobs while his wife operated the cabins.

While Pfeifer entered the tourist business after witnessing visitors in the area, others came north with clear intentions, including Jack Stedman’s parents, who operated Pine Woods Overnite Log Cabins near Brainerd. Stedman lived in Rochester through ninth grade. The family traveled to Brainerd after a friend mentioned a cabin business was for sale. Pine Woods had electricity when they bought it in 1938, and they added indoor bathrooms in the 1940s, making it truly “modern.” Pine Woods advertised through the local chamber of commerce and posted road signs. One of few Brainerd-area cabin businesses before the war, it offered privacy and reasonable rates. Most business was short-term, but the Stedmans encouraged longer stays by offering the last night free if people stayed a week.

Places like Pine Woods received repeat business but at a lower rate than resorts. One school supply saleswoman made one of the cabins her home for several years. Other visitors included people building on nearby lakes who needed a place to stay during construction. Cabins often filled up on weekends but also attracted salespeople during the week. With gasoline rationing limiting travel during the war, Stedman’s parents worked in Brainerd, but did not close the cabins. Since money was tight, the family handled all maintenance. Unlike resorts where guests often communicated with the owner about their upcoming stay, people regularly arrived at cabins unannounced. As automobile travel increased, housekeeping cabins offered visitors flexibility and emerged as an important element of the tourist landscape.

Others entered the tourist business after vacationing in the region. Ed and Kay Gilman moved to Fifty Lakes to raise their family and run Gilman’s Resort. Ed retained fond memories of fishing in northern Minnesota as a youth. After leaving the army and working for nine months, he and Kay came north on vacation and purchased an existing resort. Guests arrived from across the Midwest, including families friendly with the previous owners. Like other operators, the Gilmans depended on guests spreading the word, but they also belonged to the local resort association and advertised in the Twin Cities newspapers. Carol Crawford Ryan’s family was among those guests, visiting Gilman’s starting in 1932 when another family owned it. Carol’s father, an Iowa City postal worker, heard about the resort from a local gas station owner. The resort attracted a middle-class clientele, including civil servants and farmers. Like many young North Woods visitors, Carol’s experience led her to purchase a summer place as an adult.

The development of northern Minnesota’s tourist landscape would have been incomplete without the Ruttger family. All four of Joseph and Josephine Ruttger’s sons operated resorts—Alec at Bay Lake Lodge, Max at Pine Beach, Ed at Ruttger’s Sherwood Forest, and Bill at Ruttger’s Shady Point. Joe’s oldest son, Alec, took over Bay Lake Lodge after returning from World War I, promoting the resort at outdoor shows armed with Oscar the Muskie—a mounted northern pike sporting a steel wool beard. When Alec ran the resort in the 1920s, families arrived from the Twin Cities, but according to Alec’s son, Jack, nearly 80 percent of business came from outside Minnesota. Interestingly, Jack compared operating a resort to farming: “You don’t grow crops, but you still try and exist and raise your family and you work off the land.” While Bay Lake Lodge attracted vacationers, it was not the only place on the lake. F. I. Boone, who stayed at Bay Lake Lodge in the early 1900s, purchased land and sold parcels to friends in Junction City, Kansas. For many, fishing and escaping the summer heat were key in choosing northern Minnesota for vacation.

In 1927 the Ruttgers established Ruttger Brothers Incorporated, which included the Bay Lake Lodge, Bay Lake Store, and a Deerwood store. Max’s brothers, Bill and Ed, who had worked in the mines and farmed, oversaw the Deerwood store. His brothers bought him out after a few years, giving Max the $2,500 needed to establish his resort. With help from local workers, Max built Pine Beach Lodge, 25 cottages, and employee housing by autumn 1931. During winter and spring, he added electricity and plumbing. A new lobby and recreation room were added in 1935, followed by six new cottages the next year. Max believed people were more likely to return if they befriended fellow guests and designed the architecture to foster community. Cottages lacked sitting rooms so guests socialized near the main lodge’s fireplace, playing cards, bingo, and other games.

The Ruttgers cooperated by placing large advertisements in metropolitan papers, and by Alec sending Bay Lake’s overflow guests to Max at Pine Beach. Pine Beach guests generally vacationed for at least one week, and some families stayed the summer. All-inclusive rates were $35 per week the first summer and when bookings slowed, they dropped to $29.75. Saturday night music and dancing attracted locals and resort guests, helping endear the resort to the community because it provided both work and leisure. Food also attracted vacationers, and when Max hired a Minneapolis restaurant chef in the late 1930s, he received acclaim from his Twin Cities guests. In the mid-1930s Bay Lake Lodge developed a children’s program, and Pine Beach followed. At Pine Beach guests used rowboats and wooden canoes before the resort added sailboats and a ski boat. Pine Beach opened in the midst of the Depression, but business continued to flourish.

New tourist facilities also fostered opportunities. Bishop’s department store in Park Rapids served locals but benefited from tourists visiting neighboring Itasca State Park by selling clothes to those unprepared for the weather. While some area resorts expressed displeasure with park competition, proximity ultimately boosted business at local establishments like Bishop’s. Others provided entertainment, with Carl Warmington performing music at Breezy Point Resort and Tom Madden operating slot machines at area establishments. Tom’s nephew Jack, who later opened his own resort, stayed at Ruttger’s Pine Beach during its first summer to oversee his uncle’s business. The Maddens also ran a golf course, selling tickets for resort owners to distribute to guests.

While resorts and lodges offered entrepreneurial opportunities and places for tourists to stay, some people reshaped communities and the landscape by building or purchasing summer cottages. During the 1910s the Forest Service platted Star Island in the Chippewa National Forest and opened it to cottage development. The south shore offered a concrete sidewalk along the beach and a resort-like atmosphere, attracting businesspeople from the northern plains. The west shore was more rustic with no beach and swimmers using docks, while the east shore attracted professors and doctors. Summer residents brought with them the social markers of their place in urban society, creating a hierarchical structure in this vacation community. But residents also cooperated, establishing the Star Island Protective League in 1916 to encourage the government to establish ranger, telephone, and dock service for better fire protection. Despite constructing cottages on the island, which ultimately limited wider public use, residents claimed national forests were public playgrounds and worked with the Forest Service to control timber harvests.

Star Island summer visitors also hired local residents. Des Moines attorney A. J. Starr contracted with a local concern, Lydick Mercantile, to build a summer cottage on Star Island. Far from luxurious, it was a haven in the woods for this professional man and his family. Between 1909 and 1918 Cass Lake residents helped build numerous Star Island cottages, and the island had one summer resort by 1926. By 1941 Cass Lake advertised itself as the center of the forest. Visitors could stay in developed forest campgrounds or choose among 360 area resorts. The Forest Service continued issuing permits for summer homes, resorts, and camps, helping increase local work opportunities by generating tourist expenditures.

While new accommodations changed the landscape and vacation experience, tourism also altered regional employment even as it aligned with a long regional tradition of seasonal work. Dunn’s employed local women to clean, cook, and wait tables, while men served as guides and handymen. In 1937 sisters Ida and Ada Mellum of nearby Pelican Rapids wanted dining room work. For many, resort work provided money while in school or away from teaching. Inquiries also arrived from those wishing to summer in the area. School principal Albert Farnham inquired about employment for him and his wife and planned to bring their children. Others, like Margo Cairns of Minneapolis, were told to inquire at larger resorts like Ruttger’s. By 1945, with war forcing resort closures, potential employees also turned to the State Tourist Bureau to see if northern resorts were hiring.

Some expressed a desire to work at northern resorts and experience natural surroundings, but others found employment by chance. Ruby Treloar and her family farmed five miles from Ruttger’s Bay Lake Lodge. As a girl, she recalled that the “Ruttger’s name was always something real high-class and over and above all us farm people.” This did not stop local residents from working summers at the resort, given the pay and opportunity to meet new people. Initially Ruby had little intention of working there. She wed in 1939, spent a year in Hinckley, Minnesota, and another in New York City before returning home in 1941. When Alec Ruttger went looking for local help, he persuaded Ruby to work for his family. She first worked for his brother Max at Pine Beach, but the following year returned to Bay Lake Lodge to lead the dining room staff and remained there for over 50 years.

Across northern Minnesota operators marketed rustic outposts offering comfort and adventure amid natural beauty and rustic surroundings. The state’s 1949 Tour Guide to Minnesota reported on tourist industry growth since 1900, capturing an enormous investment of time, money, and labor. Lodging owners provided vacationers a place to stay and an experience that depended on a new workforce, landscape, and promotional language that linked city and country. Work remained connected to the land but instead of felling trees or mining ore and shipping goods to cities, it often meant caring for a new crop of tourists who consumed the region’s forests and lakes. For many visitors, northern Minnesota came to be viewed as a place of leisure rather than labor, as a retreat from urban life rather than an economic storehouse of timber and iron ore.

As one type of economic storehouse faded, another emerged. A second 1920s Minneapolis Daily Star cartoon portrayed tourists as quintessential consumers, paying for goods and experiences. Highlighting tourism’s economic impact with the expression, “I’ll take $100,000,000 worth of that!,” the cartoon also aimed to convince residents that in-state vacations offered enjoyment at reasonable prices. Allusions to escape appeared in promotional literature and highlighted how conservation efforts contributed to a new tourist landscape. In its 1919 A Vacation Land of Lakes and Woods, the U.S. Forest Service emphasized opportunities on public lands, labeling the Superior National Forest an “ideal recreation ground for the camper, the fisherman, and the canoeist.” Canoeists would see a country described in evocative language to entice visitors, which supposedly had changed little since fur company brigades plied these waters. The agency offered summer home sites for lease and worked to improve access. Beginning in 1922, the St. Paul Pioneer Press’s annual vacation section, “Call of the Open,” broadcast northern Minnesota to Twin Cities’ residents, while federal agencies and regional organizations produced literature extolling the region’s vacation virtues.

Chambers of commerce and regional organizations also acknowledged tourism’s economic benefits, informing their promotional efforts. Ely pitched itself as the Superior National Forest gateway, providing services and supplies to vacationers. In the early 1930s the Ely Commercial Club promoted rustic resorts and lodges with capacity for over one thousand people, suggesting it was a place where “breezes that fan its streets carry the perfume of the balsam, and its sky line is the jagged whip-saw of the pines in sharp relief against a clear blue.” Such descriptions highlighted how natural environs could overwhelm the senses. Materials promoting Ely said little about surrounding mines, despite the fact that they employed 1,500 people with a monthly payroll of $200,000. No tourist would have been unaware of their presence, although local promoters emphasized natural beauty and concealed Ely’s connection to the smoke-filled industrial city in order to sell the place to vacationers seeking escape.

MAA promotion emphasized outdoor adventure, including a trip along Lake Superior’s North Shore to enjoy fishing hamlets, the towns of Two Harbors and Grand Marais, and the expanding commercial roadside, including “summer places skirted by refreshment stands and filling stations.” Others might venture to the national forests, iron ranges, or Itasca State Park. The MAA enticed vacationers with the slogan, “Come to the Arrowhead, where the climate is sublime, come in the winter and in the summertime.” It emphasized historical lore, with stories of Indians, trappers, fur traders, and lumberjacks. Canoeists could “hunt with a camera” to capture scenery. If roughing it in a canoe did not suit one’s taste, the Gunflint Trail and its lodges catered to outdoor enthusiasts year-round.

While many who promoted the North Woods lived and worked in the area, urban businesses also saw opportunities. St. Paul’s Schuneman and Evans department store published Tips on Minnesota Motor Trips to sell its camping gear, remarking, “It’s all great sport—this getting away from civilization and losing yourself in the North Woods—but you can’t get along without a few conveniences.” Before leaving on a trip, the retailer urged purchasing equipment. While the store sold tangible goods, the Ten Thousand Lakes of Minnesota Association viewed Minnesota’s outdoors as a product to sell to vacationers. It suggested that the Boundary Waters remained “the Venice of the North” with waterways offering travel routes and assuring visitors that “it is a real wilderness—make no mistake about that.” Canoeists would find serenity traveling through supposedly untouched waters.

Newspaper writers also found their services in demand. In a 1938 brochure journalist and Minnesota Tourist Bureau director Ed Shave wrote an article in the form of a letter to a tourist interested in a Minnesota vacation. The “Long Bow” region, according to Shave, was a place for the explorer, voyageur, fisherman, and hunter. Tourists discovered the Cuyuna Iron Range in Deerwood and Crosby and encountered citizens festooned with long beards for the Paul Bunyan summer carnival in Brainerd, with its 362 resorts and 5000 lakes. Heading north to Nisswa, 75 resorts made vacations enjoyable and affordable. Shave told the story of one family who rented a summer cottage for less than the cost of remaining in the city. Farther north at Leech Lake, visitors entered the Chippewa National Forest with its Indian burial grounds and fishing. Looping back to Itasca State Park, vacationers could watch a pageant performed by CCC workers and Chippewa Indians. Shave closed by telling the potential tourist, “Here’s hoping you’ve enjoyed the trip—but when you make it in reality you’ll enjoy it ten thousand times more.”

Maps provided another vehicle to guide tourists through the landscape. MAA maps listed lodging and game laws, telling tourists to “Follow the Arrows to the Arrowhead” where they would discover a “climactic delight” and a “land of romance.” Others offered maps with their guides, including the Ask Benn Wagner Service of Crow Wing County, which listed 267 resorts in the area. Minnesota’s Cook County claimed the region as “nature’s gift to the Arrowhead Country” and located all resorts along the Gunflint Trail. The St. Paul Pioneer Press printed a state highway map in its 1934 vacation section. By 1938 the Gunflint Trail Association and Grand Marais Chamber of Commerce did the same, listing 59 resorts on Lake Superior’s North Shore Drive and the Gunflint Trail. A diverse set of tourist advocates, ranging from the state with its official highway maps to local chambers of commerce, incorporated maps into the lexicon and helped tourists visualize and navigate the North Woods.

As consumers of leisure, North Woods tourists made decisions about how, when, and where to vacation. But their choices were also constrained by a consumer culture in which advertising framed such decisions. Tourist literature shared common themes like hay fever relief, avoiding urban congestion, adventure, and enjoying scenic beauty, all of which were increasingly possible in northern Minnesota during the interwar years. It presented vacations as an escape from routine, capitalizing on the degradation of work that led many urban residents to seek satisfaction through outdoor leisure. As such, vacations proved crucial in shaping consumer culture and environmentalism in Minnesota during the interwar years.

Tourists from the Twin Cities and beyond followed the arrows to the Arrowhead to experience a region of rugged scenery and wilderness, adventure and tranquility, access as well as escape. In doing so, they joined the flow of people—local residents, sporting and wilderness advocates, tourist promoters, and state and federal officials—and commodities that helped create Minnesota’s North Woods both as an idea and as a physical place.