A bird's eye tour of Minnesota’s North yields dozens of rivers, seemingly infinite trees, and one very large blot that glows with an uncanny, cloudy iridescence.

Not a single natural lake along that 154-mile stretch exceeds 2,000 acres in surface area. The largest is Devil Track near Grand Marais, with its 1,876 pristine acres. The jumbo man-made reservoirs outside Duluth? They look like standard north woods lakes, just bigger.

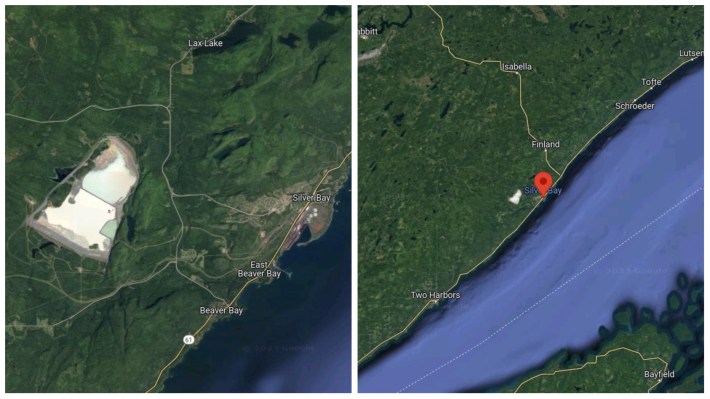

But then there is Milepost 7, the screamingly unnatural monument to decades of extraction. Currently, its dull gray waters span 2,150 acres—roughly the size of White Bear Lake—in the highland woods above Silver Bay.

You’re forgiven for not knowing it exists: Despite its massive footprint, it’s mostly hidden from public view. Lax Lake Road, which barrels down the shore from its 300-acre namesake lake, will get you close, though all turn offs are blockaded by industrial fencing, security cameras, and warning signs.

That’s because Milepost 7 isn’t a lake at all. It’s a tailings basin that stores polluting runoff from Cleveland-Cliffs Inc., the Ohio-based mining giant that processes taconite pellets five miles away on the shore of Lake Superior. Pull it up on Google Earth, and you’ll see a hulking trapezoid that, Blob-like, could seemingly absorb the entire city of 1,857 below.

And Milepost 7 is growing. Or at least that’s the plan.

In summer 2021, Cliffs cleared several major regulatory hurdles to begin a construction project that would expand the basin by 30%—a move the Minnesota Center for Pollution Control says would “directly impact” 264 acres of nearby wetlands. In the meantime, however, a fight over royalty fees caused the parent company to idle its Northshore Mining facilities in Silver Bay and Babbitt, resulting in hundreds of layoffs. The February 2022 move “stunned” local political leaders, the Duluth News Tribune reported; the publicly traded conglomerate had just posted record profits of $3 billion in ’21. CEO Lourenco Goncalves predicts the pause will last until “at least” April.

Since being green-lit, the proposed 650-acre Milepost 7 expansion has mostly faded from the public's attention. The famously tight-lipped Cliffs PR apparatus didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment. This week, Ryan Malterud with the U.S. Army Corp. of Engineers said he didn’t have any knowledge about the status of the plan; a spokesman with MPCA said "we don’t have any updates.”

For years, the Minnesota DNR's shepherding of the project has drawn sharp criticism from two environmental watchdogs: Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy and WaterLegacy. Last May, those groups co-authored a letter to DNR outlining their Milepost 7 concerns. They never heard back. Then this Wednesday, when prompted by a Racket inquiry, DNR revealed that the proposed expansion had triggered a new, ongoing environmental review. That information surprised and encouraged MCEA and WaterLegacy, who've loudly questioned why the agency was previously set to rely on reviews from the '70s. Plenty of skepticism remains.

“DNR had blown us off. They created literally thousands of pages to tell us that we didn’t need to study this," says Paula Maccabee, advocacy director and lawyer with WaterLegacy. "They may be agreeing to take a baby step, but I’m asking them to take a grownup-sized step into current science. I certainly don’t feel like we’re being protected.”

The agency maintains that Milepost 7 is "the most stringently regulated tailings basin in Minnesota and meets and exceeds all current safety factors adopted by the dam safety engineering community." DNR acknowledges receiving the letter, but notes that the groups didn't "request a response."

Forty-three years ago, an epic legal battle concluded with the creation of Milepost 7, which was intended to save Lake Superior from the polluted tailings Reserve Mining had subjected it to for decades. The uncertain future of those murky waters is head-scratching, considering the basin—which must be maintained in perpetuity to prevent leaks or overflow—teeters above 10% of the world’s fresh water.

“People still remember the ’70s. These very same tailings exist, just a little bit upstream now,” says JT Haines, Northeastern director of MCEA. “Our standards for dam design and independent review are sorely lacking in Minnesota—Milepost 7 is another example of a potentially huge problem.”

The Landmark Legal Case that Spawned Milepost 7

Younger Minnesotans might not remember the water panic that gripped Duluth 50 years ago. Since the 1950s, Reserve Mining Co. had been smashing giant rocks to extract tiny bits of ore, then dumping the resulting liquified slurry directly into Lake Superior from Silver Bay. By the 1970s, chemists at the freshly created Environmental Protection Agency started detecting microscopic asbestos fibers in the downstream plume, which eventually extended all the way to the Twin Ports.

In 1973, as the EPA scrambled to determine whether the fibers posed health risks to Duluthians, the city used a $100,000 grant to supply bottled water to citizens, the Minneapolis Star reported at the time. The EPA advised parents to not let children under five drink municipal water, the AP reported, and Duluth water was banned for commercial transport beyond state lines. Said the EPA’s Francis T. Mayo in ’74: “The review of evidence presented in the Reserve Mining Co. case indicates a significant health hazard is likely to be associated with the presence of these asbestos fibers.” By 1975, Reserve Mining was still discharging 67,000 tons of taconite waste into the big lake daily, expanding Minnesota’s physical surface area like lava via a so-called tailings delta. This infamous photo shows what that looked like in practice:

“The engineers who invented it were quite pleased with themselves; the theory was, the solution to pollution was dilution,” says Southern Illinois University history professor Jeff Manuel, who published a history of Minnesota taconite mining, Taconite Dreams, in 2015. “To our eyes today, it looks pretty horrific to take huge volumes of industrial waste and just pump it right into Lake Superior.”

Not everybody was worried at the time. "In the early ’70s, the fact that a lake was green instead of blue wasn't the end of the world to most people," Byron Starns, then a young MPCA lawyer, told MPR News in 2003. Reserve Mining certainly wasn’t, and it fought like hell to preserve the status quo. During a trial that began in 1973, U.S. District Judge Miles Lord demanded cleanup answers from C. William Verity. The Reserve executive’s reported reply? “We don't have to, we won't.”

All along, Reserve hinged its case on the argument that disposing of tailing on land was impossible, that the company simply had to dump into Superior. That legal strategy unraveled when it was revealed that Reserve had boxes upon boxes of detailed engineering plans for on-land tailings basins. Judge Lord was displeased, and ordered mine operations to cease immediately in April ’74. The decision made national headlines, MPR reports, and overnight the U.S. lost one-twelfth of its iron ore production.

"The water [Duluthians are] drinking is poisonous and will kill their children," Judge Lord said in a ruling the following year that ordered Reserve to pay for ongoing filtration costs.

Those poisons would be pumped into Superior for another five years. A federal appeals court ruled that, while Reserve must eventually relocate its runoff, the company could resume production until that date, thus saving an estimated 3,000 jobs. In 1980, the Milepost 7 tailings basin began housing the waste that put Duluth at the center of ’70s environmental regulation debates.

“Initially, the idea of having the tailings pond in Babbit, where the iron ore was mined, seemed more attractive to regulators, because it was a beat up, scarred landscape,” Manuel says. “Milepost 7 was a compromise solution.”

While “the public health risks from taconite were wildly overblown during the trial,” Manuel concludes in Taconite Dreams, “The trial, and the larger issue of industrial pollution, forced miners, engineers, and other proponents of economic development on the Iron Range to confront new and complex factors.” Politically, the jobs vs. environment battle further cleaved unions away from the green movement, he writes, resulting in the increasingly fine line Arrowhead DFLers must walk as the region transforms into a tourism mecca.

The ’80s weren't kind to the U.S. steel industry, and Reserve declared bankruptcy in 1986. All those union jobs vanished yet again. Under new non-union parent company Cyprus-Amax, the Babbitt mine plus the Silver Bay processing plant/tailings pond reopened in 1989 as Cyprus Northshore Mining. Cleveland-Cliffs, another non-unionized outfit, would acquire the properties in 1994. After Reserve folded state officials dangled a carrot to industry with hopes resuming mining ASAP: Any new owner wouldn't be liable for past Reserve pollution, the Duluth News Tribune reported. Among the would-be liabilities unearthed so far at Northshore Mining: 3,000 tons of tires, 12,500 rusted drums, an ash pile, and a sludge pit.

“The industry got crushed in the ’80s, from Pittsburgh to Chicago,” Manuel says. “And you start having big pollution questions. Because taconite is a low-grade ore, it requires a vast increase in the amount of material that’s mined out of the earth. If you only need a small percentage of the material, most of it is just waste. And you gotta do something with that…”

What Do You Do with That?

Throughout 2021, as the DNR, Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, and U.S. Army Corp. of Engineers stamped permits for the Milepost 7 expansion, those original basin designs became flashpoints yet again. That summer the DNR determined that, since the project’s scope doesn’t exceed the acreage studied in a 1975-76 environmental impact statement, no new review was required.

“The idea that they’re relying on a chicken scratching from 1975, rather than doing environmental review under modern standards, is so shocking to me,” Paula Maccabee with WaterLegacy told the Duluth News Tribune in '21.

The agency granted a permit for Cliffs, followed shortly by MPCA and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers each issuing their own. Those decisions paved the way for: the 650-acre ballooning of the existing basin; the relocation of a railroad embankment to make room; and the heightening of existing dams by around 60 feet. However, the plans were "halted pending receipt of new information from the company" last summer, DNR tells Racket. A "mandatory Environmental Assessment Worksheet" had been triggered the previous year.

“I stand by what I said before. They’re letting the mining companies call the shots in secret, and not updating the science," Maccabee said Wednesday. "I want to make it really clear, that what WaterLegacy is asking for is not just the EAW, which is like a checklist. We’re asking for a comprehensive environmental impact statement that will look at not only the the day-to-day pollution, but what has to be done according to modern science to make sure that Milepost 7 doesn’t catastrophically fail, poison the Beaver River and its tributaries, Lake Superior, and Silver Bay.”

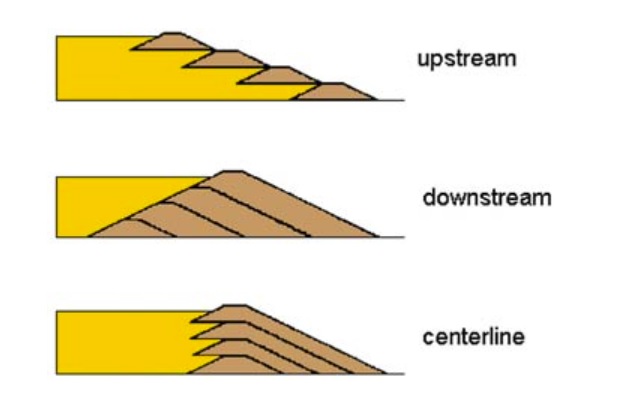

Some environmental advocates, like the MCEA and WaterLegacy, have argued for years that large-scale construction on a barrier this important warrants a new environmental review. Especially since the expanded tailings dams will be built, in part, using the upstream construction method, which has been banned in Chile, Peru, and Brazil over inherent safety concerns, Reuters reported in 2021. Upstream dams are cheaper to build because, instead of more material, “you can actually use [the] tailings for physical support,” engineer/geophysicist Dave Chambers told Frontline in 2012.

You can find a granular breakdown of the dynamics behind upstream construction here. Or simply consult this colorful illustration:

The DNR matter-of-factly determined that concerns about upstream construction are “simply not an issue at Mile Post 7,” since Northshore Mining intends to use the hybrid “modified centerline" (aka "offset upstream") method.

“Milepost 7 is a large facility holding a lot of pollution, and there’s no dam safety permit,” says Haines with MCEA. “We’re glad to hear that DNR is taking some action on this, though it does not appear the statement they provided responded to the important issues we raised. With these black-box DNR decision-making situations… it’s important to have a little sunshine on ‘em, and I’m glad there’s a conversation that’s happening.”

DNR says the new environmental review, which will encompass "dam extensions, the rail line relocation, and the proposed stream mitigation projects," will be subject to a public comment period upon its completion. The agency, in its statement to Racket, claims it had kept MCEA abreast of the zigzagging Milepost 7 expansion saga.

That joint MCEA/WaterLegacy letter from last spring implored DNR to resolve four key Milepost 7 expansion issues “in a timely manner,” whether or not the project was fast-tracked or stalled. Their very lawyerly missive demanded that the agency require Northshore Mining to obtain dam safety permits for Milepost 7; asked for set dam safety and mining permit terms; requested that a heavily redacted 2012 dam break analysis be made public free of redactions; and, perhaps most interestingly, called for a review of Northshore Mining's financial commitments related to the potential closure of Milepost 7.

In its own documents, Northshore Mining admitted the cost to “close the basin, drain the pond, and reclaim the disturbed areas was estimated to be as high as $70 million”—in 1986 dollars. In 2020, the company stated it is currently on the hook for $4 million, a total the letter describes as “palpably inadequate and would only cover a fraction of the Milepost 7 tailing basin’s closure costs.”

Tailings Basins, Here and Abroad

Milepost 7 is far from the largest tailings basin in Minnesota. It just happens to loom over sparkling pure water, popular resorts, and heavily trafficked state parks like Split Rock Lighthouse. Over on the Iron Range, the eerie glow of wastewater ponds can be seen via satellite from Virginia to Bovey.

A lifelong Iron Ranger, Aaron Brown is a writer, radio host, and college instructor who lives and works near Hibbing. He’s currently working on a book about the origins of the Iron Range.

“The overhead view of the Iron Range, the tailings basins are the most dominant feature,” he says, noting that mining companies describe them as inert and non-toxic. “They’re enormous, they look like inland seas. About the only way you can see them, on the ground, is to jump across a ditch and scamper up these big dirt walls.”

Like fellow author Manuel, Brown acknowledges that Milepost 7 probably receives surplus attention due its proximity to prime Minnesota tourism real estate. The Range, as Manuel notes, is something of a landscape “sacrifice zone.”

In his forthcoming book, Brown details the state's first-ever de facto tailings basin, which happened to be a tiny Iron Range lake near Nashwauk. Around 1910, a mine began dumping waste water into it. By 1913, that polluting residue had seeped its way to nearby Swan Lake, a popular hangout for Hibbing’s elite.

“After a big rain, it turned Swan Lake bright red,” Browns says. “It would have appeared almost biblical.” Victor Power, then the mayor of Hibbing, sued the mine company, resulting in perhaps the first mining industry environmental lawsuit in northern Minnesota history. Power lost the case due to the lack of color photography—there was no way to prove Swan Lake had assumed the color of blood. “It didn’t succeed as a lawsuit, but it sufficiently scared the mine to build the first tailings basin in Minnesota, mostly out of the fear of litigation,” Brown says.

Globally, Brazil comes up a lot when discussing the potential for tailings basin disasters. In 2019, the collapse of the Córrego do Feijão Tailings Dam in Brumadinho resulted in the country’s deadliest mining disaster, killing almost 300 people under waves of runaway sludge.

Four years earlier, the rupture of Samarco's Mariana dam killed 19 and spilled around 40 million cubic meters of tailings waste into Rio Doce Basin; it’s considered the country’s worst-ever environmental disaster.

Closer to home, the 2014 Mount Polley breach sent 8 million cubic meters of tailings—plus another 17 million of water—into the watershed of remote British Columbia, Canada. WaterLegacy's Maccabee says she's disturbed by the construction and placement similarities between Mount Polley and Milepost 7.

“Back in the 1970s," she says, "it was calculated that if even one-tenth of Milepost 7's dam collapsed, it would produce a 28-foot wall of water moving down the Beaver River valley at more than 20 mph toward Lake Superior. That’s serious business.”

After a Milepost 7 pipeline broke in 2000, 10 million gallons of tailings slurry did, in fact, wash into the Beaver River watershed. As a result, Northshore ended up paying almost $500,000 in fines plus related environmental restoration efforts, according to MCEA.

The unavoidable issue with this type of storage? It’s estimated that tailings dams, on average, must maintain their integrity for 10,000 years to avoid catastrophic failure, according to the National Parks Service. For context, Japanese construction firm Kongō Gumi is the oldest company in the world, per this strange Wyoming lawyer’s infographic, though it has only been around for 1,445 years. That 10K figure “implies a significant and disproportionate chance of failure for a tailings dam,” NPS concludes.

Complicating matters here: Brown says folks on the Iron Range are worried that Northshore Mining won’t ever reopen on a permanent basis.

“Who pays for tailings basins? Bankruptcy ends a company,” Brown says, speaking generally. “Ultimately, this is, longterm, a state of Minnesota problem—we’re going to be on the hook.”