The Rocketman has two years to live.

As he sits inside the movie theater of his landmark house in Bloomington, Ky Michaelson sounds at peace with that fact. Failing kidneys, at age 86, aren’t all that remarkable, but they might be the only unremarkable thing about the Rocketman’s life.

Record-setting drag racer.

Pioneering Hollywood stuntman.

Serial entrepreneur.

Prolific rocketeer who, in 2004, became the first civilian to launch a rocket into space, besting the 20+ other teams pitted against each other in an amateur space race.

On a recent July afternoon, Michelson, rocking his favorite hot rod button-up and signature mustache, crackles with enthusiasm as we tour his 7,500-square-foot home, which is more or less a monument to his life. His son Buddy, whose legal middle name is Rocketman, tags along, as does Ky’s much younger girlfriend, Peggy. This is clearly the Ky Michaelson show, however. The man once referred to as the “P.T. Barnum of amateur rocketry” and “the sultan of thrust” hasn’t lost his fastball.

Michaelson’s chronic asthma and achy back necessitate frequent sitdowns, but he’s determined to show off a living room that’s overwhelmed by Rocketman memorabilia—from one of his earliest boyhood inventions (an electric hot dog cooker dubbed Ky’s Little Cremator) to his greatest Hollywood achievements (one of his 13 rockets built for the movie October Sky).

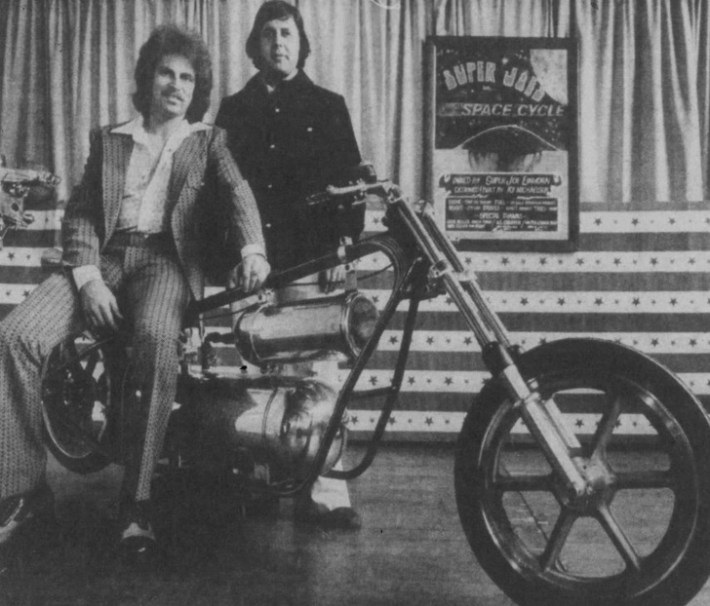

Where most folks might place a credenza, there sits a rocket-powered wheelchair and a rocket-powered tricycle. Next to the fireplace? An honest-to-god jetpack. Beneath a 100-gallon fishtank? A motorcycle that a mysterious daredevil, the Human Fly, once used to clear 27 buses inside Montreal Olympic Stadium, more than doubling Evel Knievel’s best jump. And that’s just a fraction of the stuff tied directly to Michaelson’s singular career. Among the tchotchkes won via online auction: a charred panel from the doomed Challenger mission, a toilet from the Russian space station Mir, a functional chrome cannon, and way more dinosaur bones than you’d expect to find inside a first-ring suburban home.

Michaelson and Buddy beam with pride from inside their sprawling garage workshop, where 15-foot rocket cars rest next to rocket-boosted snowmobiles. (Buddy, the youngest of Michaelson’s 13 children, has been trained since he was a toddler to assume the Rocketman mantle.)

We head to his home movie theater, where Discovery Channel blares from the 100-inch TV screen. Lining every inch of wall space, 8x10 autographed portraits of Red Skelton (complete with Red-chomped cigar), the Fonz, Burt Reynolds, and Arnold Schwarzenegger smile down with memories of the 200+ films, shows, and ads that featured Michaelson’s stunt work.

Like in any halfway decent movie script, Michaelson’s arc has been fraught with obstacles to overcome: dyslexia, bullies, the shocking death of his stuntman best friend, bottoming out businesses, three divorces, battles with government regulators, and, throughout it all, the laws of physics that conspire to defy all rocketmen. Today, Michaelson presides happily over his castle-like museum of a home, content to live out his remaining years among the thousands of larger-than-life artifacts that justify his self-styled credo: If you can dream it, you can do it.

As our four-hour interview winds down, the Rocketman dials up a sizzle reel for the unreleased documentary about his life on the big screen. The decade-long project was developed by the production company behind A&E’s Intervention and TLC’s Sex Sent Me to the ER, though it remains a quarter-million short on funds.

"They're trying their hardest to get this thing sold,” the subject says of his doc. “It's gonna be made, whether I'm around or not, but I'd sure like to see it. I’ve done some crazy shit—a lot of crazy shit.”

Rocketboy Becomes Rocketman

Since he was five, Ky Michelson’s life seemed destined to involve flight—its promise and its peril. In 1944, a B-26 bomber crashed one block from his south Minneapolis home near Lake Nokomis, killing six. Young Ky saw the towering flames from his front yard. "Had the crash occurred an hour later, school children, out for lunch, might have been crowding the area," the Minneapolis Star reported at the time.

Michaelson was born into a legacy of speed, too.

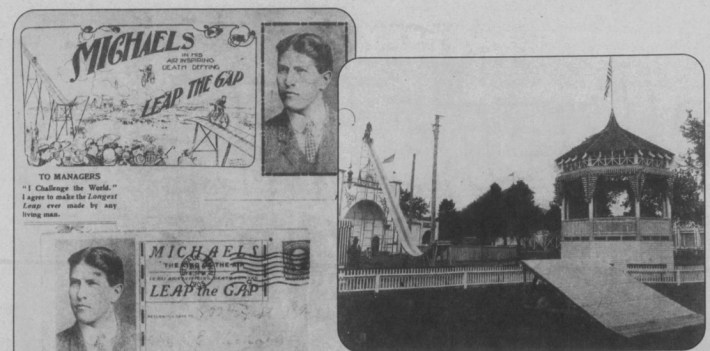

From 1908 to 1916, his grandfather and great uncles ran the Michaelson Motorcycle Co. in Minneapolis, which secured some of the earliest patents on clutch and muffler technology. (Michaelson, who has never drank or smoked, honored the family brand by inventing a beer-powered motorcycle that recently made national headlines.) His great uncle, John, was a regionally famous daredevil.

Ky describes his father, Howard, as a "very, very intelligent but quiet" man who built telescopes and read obsessively when not working on instrumentation for Northwest Airlines. His inventive nature made the news in 1952, with the Minneapolis Star screaming "MECHANIC'S HOBBY: Plane Parts Make Good Telescopes."

Living in a single-bedroom south Minneapolis home with his wife, Pearl, and three kids, Howard suffered from nagging medical concerns and related debt. Ky strikes a hushed tone when talking about his father’s WWII flights over the Wendover, the Utah airfield where B-29 bomber crews prepared for the atomic attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. “They were drilling holes in his head, all kinds of stuff, trying to figure out why he felt funny," Ky says of life after the war for his dad. In 1968, Howard’s body was discovered in the Mississippi River.

"They did an autopsy, and a tumor had burst in his brain,” Ky remembers. “In the 1970s, we got a call from Washington, D.C., saying they wanted to have a conversation about my dad. They wanted to exhume his body to see if it had any radiation, but my siblings didn’t want to.”

Years earlier Howard had introduced Ky to the world of mechanical tinkering, and by third grade the youngster was building his own radios. At 13, he was explaining a crude homemade diving bell—junked hot water heater, garden hose, tire pump—to cops on the shore of Lake Nokomis. That same year, he’d get his first chemistry set and first tattoo.

Michaelson still gets a kick out of recounting his boyhood adventures. With giddy excitement, the octogenarian promises that there are "at least three people alive” who can confirm his two wildest tales, because they’re “too bizarre to comprehend.”

After Michaelson hands this reporter his phone, buddy Rich vouches that, yes, the boys ran with a crew that raised a $90 mail-order lion in a rented Minneapolis basement one summer, feeding the increasingly stinky beast raw steaks through a makeshift wire cage at the top of the staircase. The Minneapolis Star archives verify the story about Michaelson & Co. discovering a cache of dynamite inside Dead Man’s Cave along the Mississippi, setting off a summer of shocking booms around the South Side. "If you hear a loud explosion, it's too late," reads a killer lede under the 1952 headline "Two Boys Take 300 Dynamite Blasting Caps."

"At times, I thought, this guy is bullshitting me,” says veteran Twin Cities journalist Mike Mosedale, who authored an excellent Michaelson profile for City Pages in 1999. “But then he'd pull out an old photograph or newspaper clipping that demonstrated his proximity to the referenced famous person or event. He seemed very intent on clinging to any and all documentation of The Greatness of Ky Michaelson.”

Michaelson didn’t feel great as a freshman at Roosevelt High School. He says his older brother stabbed the star quarterback in self defense, setting back the school’s football team when the boys involved in the incident were shipped off to other schools. That made all future Michaelsons targets for bullies, and rail-thin Ky was already easy prey because of severe dyslexia, which dashed his earliest dream of becoming an astronaut. Bullying and beatings were relentless, he says. He’d drop out in ninth grade.

“I hated school,” Michaelson says, adding that he developed a lifelong anti-authority streak following spats with teachers and judges. “My outlet was cars.”

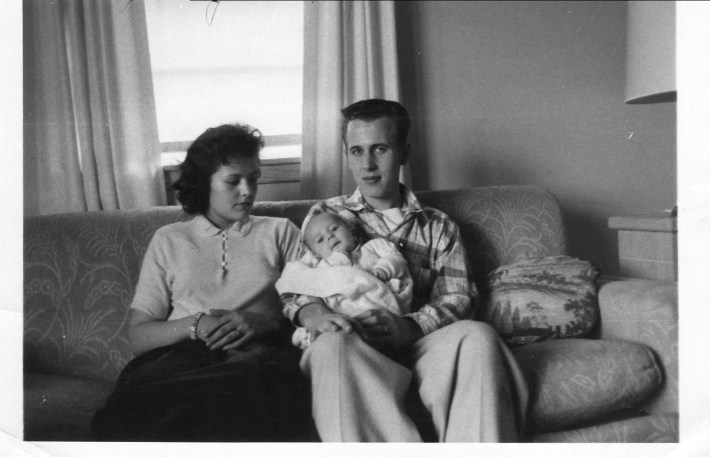

His first car, a 1933 Ford three-window coupe, set off that teenage love affair with horsepower. A simultaneous love affair with his girlfriend, Judy, resulted in marriage at 16. "I thought I was in love! We're having sex and all that..." Michaelson says, acknowledging that teen weddings were not the norm, even in the ‘50s. Yet again, there are receipts: He became a father at 17.

Hotrodding Into Hollywood

Michaelson co-founded the Gopher State Timing Association in 1954, a move to consolidate the various hot rod clubs—the Cogs, the Combustion Cousins, the Rod Nuts—that’d spend weekends tearing down Lake Street. His drag-racing career took off in the early ‘60s as he worked several day jobs at Minneapolis’s still-hopping Mel-O-Glaze Bakery and at an aluminum window factory. At age 24 with three kids, Michaelson also started a motorcycle repair business from the basement of his Richfield home. Around this time he’d travel the National Hot Rod Association circuit with his growing family, and toward the end of that decade he’d formed the 18-car Midwest All-Stars dragster crew.

“I'm the highest paid drag racer in the country,” Michaelson says, noting that his “Rocketman” branding came to him in 1964. “And I come up with this hairbrained idea: I'm going to set a land speed record in every state in the United States.”

That’s exactly what he did, setting 72 state, national, and international records. One stunt involved him roaring across Yellowstone National Park at 180 miles per hour inside a rocket-powered snowmobile.

"Ky struck me as a classic '50s motorhead, a guy who believed in the magic/redemptive power of shiny chrome, dual exhaust, and custom flame jobs," says Mosedale, the old City Pages writer.

Prize money from drag racing afforded Michaelson the opportunity to buy his current Bloomington HQ, where he started building rockets for other dudes who’d heard tales of a Minnesota-launched speed demon piloting rocket-powered vehicles. (His fascination with rocketry dates back to the matchhead and pipe rockets he’d cobble together as a boy.)

Michaelson says one day a stuntman visited his workshop. He’d arrived with a busted catapult, hoping the Rocketman could repair it. "Who built this piece of junk?" Michaelson remembers saying. And with that, the racing career was put on hold for a new one in show business.

"Now, all of a sudden, I'm a stunt coordinator,” he says matter of factly. “I'm in the business, and I'm involved with the top people in Hollywood."

Michaelson’s marriage didn’t survive his transition to the film industry. But in L.A. he’d form perhaps the most important relationship of his life with top stuntman Dar Robinson. The two men became close friends and in-demand stunt partners—Michaelson the engineer, Robinson the performer.

"I built equipment that had never been built before,” Michaelson says. “All the stunts we'd do, there were no Band-Aids—it'd either work or you'd be dead.”

The duo worked on several 1980s Burt Reynolds vehicles, including Sharky's Machine and Stick. "Totally a guy's guy: Burt wanted to hang out by the bar, play the piano, and sing,” Michaelson reports. They landed over a dozen TV appearances on That’s Incredible and Super Stunts; the latter featured Robinson jumping from Toronto’s 1,815-foot CN Tower. That stunt hinged on one of Michaelson’s inventions, the Decelerator, which more or less functioned like a giant fishing reel that kept Dar off the pavement.

During his Hollywood heyday, the nearly viceless Michaelson relished the big time. "I like women, first off: I've dated some very lovely ones, movie stars, people in the business—a lot of them,” he says. Michaelson and Robinson platonically befriended the deaf stuntwoman Kitty O'Neil, who worked as Lynda Carter's double on the TV series Wonder Woman. Years later, Michaelson says he became her legal guardian and, briefly, roommate in Bloomington after her handlers took advantage of her.

But tragedy struck in 1986, and Michaelson says he saw it coming in a dream. After waking in a cold sweat, he frantically tried dialing Robinson on set to warn him. He couldn’t get through. Days later he’d learn his bloody nightmare had come true.

While filming Million Dollar Mystery near Utah's Glen Canyon, Robinson missed a sharp turn on his stunt bike and went flying off a cliff. Due to miscommunication between rescue teams, the stuntman bled out for nearly two hours before dying in the desert, according to Michaelson.

"He was my best friend, and I saw him die in my sleep… It broke my heart,” he says. Word of the premonition traveled far and wide. "I told him later, 'If you ever think something's gonna happen with me, make sure to call,'” Ron Braun, a friend from Michaelson’s dragster days, told City Pages in 1999.

Since Michaelson refused to work with any stuntman other than Robinson, he returned to Minnesota to focus on various biz projects, including one that City Pages described as a multi-level cosmetics company. ("I've owned so many companies, you can't even imagine,” he says today.) Major spending ensued—racecars, world travels, large boats.

Michaelson refuses to talk about the late '80s and early ‘90s, but court records indicate he was subjected to a volley of business-related lawsuits. An "acrimonious" divorce from his second wife coincided with the legal woes. All Michaelson would say about that dark era was an old saying of his mother's: "Trust few, and paddle your own canoe."

Civilians Racing Toward Space

In 1994, rockets saved the Rocketman.

Michaelson had noticed that the Tripoli Rocketry Association, an international nonprofit that serves as the governing body for amateur rocketry, had ballooned to over 10,000 members. He figured he could outdo the top rocketry men of the day, so he traveled out to Nevada’s moonlike Black Rock Desert, the annual home of Burning Man, to launch a 19-foot aluminum rocket. It didn’t go as planned. "That thing frickin' grenaded! Everybody jumping under the frickin' trucks, flames and shit,” Michaelson remembers with a laugh.

But the high-octane showman succeeded at something he’d always had a knack for—getting attention.

"Nobody knew him, and he showed up with this massive rocket," Bruce Lee of the Tripoli Rocketry Association told City Pages in 1999. “Even though it blew up, people were impressed."

The next year Michaelson, freshly married to his third wife, broke Tripoli’s height record.

Hooked on rockets, Michaelson began traveling the country throughout the late ‘90s, hitting up as many as 14 rocket events per year. He hatched yet another new company, Rocketman Enterprises, which at the time supercharged model rockets with names like Big Kahuna and Sky Hawg. (Today, Rocketman Enterprises sells aerospace-grade parachutes, with Ky and Buddy sewing the ‘chutes themselves from a terrace overlooking their indoor pool.) A fitness equipment business percolated, and his cosmetics company even resurfaced with a more traditional sales model.

"I wanted another goal, so I thought: What would it take to put a rocket into space?” Michaelson says. “It all goes back to getting kicked outta school, being dumb, I don't want your kind around here. That's the attitude I got: Ever since that day I've been set on kill."

In 1997 Michaelson launched the Civilian Space eXploration Team with the express purpose of becoming the first civilian team to send a rocket into space.

At the time the Space Frontier Foundation, a California nonprofit dedicated to the "exploration and development of space" through "the power of free enterprise," was offering a $250,000 prize through its C.A.T.S. (Cheap Access to Space) contest. To win, contestants were required to send a rocket 120 miles in the air while carrying a 4.5-pound payload; “substantial” assistance from the government was forbidden. (The Kármán line, widely considered to represent the cusp of space, floats 62 miles above sea level.) By late 1999, only a handful of the 20-odd competing teams had managed to crack 20 miles of distance.

Government penalties threatened to cancel any potential winnings. Michaelson says the punishment for unlicensed space rocketry amounted to a quarter-million dollar fine and five years in prison, with five different federal government agencies watching over civilian space activity. Those bureaucratic hurdles “brought out the Johnny Rebel” in Rocketman.

“‘You’re my public servant! What's wrong with an American being the first civilian putting a rocket into space?’” he remembers yelling at the feds. “I got all worked up in a frenzy."

Founded in 1983, the Office of Commercial Space Transportation, the permitting agency for private-sector space exploration, did not issue a single permit until Michaelson secured his in the early ‘00s. It took some lucky breaks.

During a launch at the alkali flats of the Black Rock Desert, Michaelson says he was approached by a mysterious individual who remarked, "Ky, you're sure the talk of Washington, D.C. but they're never gonna give you your license—they'll ask questions that there's no way for you to calculate." He says that man had possession of a program that could run thousands of impact simulations, and that he offered his help. He thinks the avalanche of government paper work—bonding, insurance, environmental impact studies, licensure—was intended to overwhelm his dyslexia.

The C.A.T.S. prize evaporated after "the 9/11 thing happened,” Michaelson says, adding that rocket restrictions intensified during the War on Terror. But he remained deadlocked with 25-30 other teams competing in the civilian space race. The process consumed him, he says, draining hundreds of thousands of dollars from his bank account.

One day before his first attempt at space, Michaelson’s team acquired their license. But that rocket exploded. Ditto for the next one. Meanwhile, Michaelson’s mother died and marital issues with his third wife intensified. He says his finances were dire and that a wealthy saboteur, who’ll remain nameless, stole Civilian Space eXploration Team’s data while attempting to block its access to propellant. "My whole world is frickin' collapsing,” Michaelson remembers.

Then, on May 17, 2004, Michaelson made history: His rocket soared 72 miles into space, travelling at 3,580 miles per hour.

"Everything went perfect,” he says. “It was the happiest feeling ever in my life. I freaked out man, I freaked out."

The only (very minor) downside? Video footage his rocket recorded from space has been seized on by Flat Earther conspiracy theorists. "My god, I get people terrorizing me at my house because I proved the Earth is flat with my frickin' rocket!” says Michaelson who, for the record, believes the Earth is round.

Michaelson, ever the self-promoter, offered the following in a New York Times story about his “gonzo subculture” two years after shooting the first amateur rocket into space: “A lot of guys close their eyes and see women. I close my eyes and see rockets.”

Rocketman’s Legacy

Back inside the Rocketman’s over-the-top Bloomington home, the irrepressible Michaelson excitedly shows off clips highlighting his long, never dull career.

There’s the 1982 local TV news feature on his second wedding, a Wild West-themed bash that included a bride/groom gallows hanging, fistfights between the dozens of stuntmen in attendance, and Dar Robinson, the best man, being set on fire. "I did the whole thing for under two grand, because I got friends—best wedding ever,” Michaelson beams.

There’s the stunt he helped coordinate in 2017 for Eddie Braun, who successfully cleared Idaho’s 1,400 foot-wide Snake River Canyon in a rocket modeled after the one that failed to deliver Evel Knievel over the same canyon in 1974. "Evel was a jerk, he screwed a lot of people over,” Michaelson observes.

When the YouTube app dims, we turn to the question of legacy.

Michaelson estimates his tally of grandchildren—all the way up to great, great, great—exceeds 100. His “beautiful family” is in good shape, he reports. He’s confident that Buddy, 25, can keep things humming around the house after he’s gone. He knows everything about the operation, Michaelson says, and there is a lot to know. The money’s where it needs to be, even after three costly divorces and whatever happened during the George H. W. Bush era.

"I've had my ups and downs in business, but I've always figured out a way to make money," Michaelson nods. There's a Corvette (license plate: STUNT1) and a hotrod (ROCKET2) parked outside his lakeside property, but he prefers to drive his girlfriend around in their "beater" Mercury sedan.

As he nears the finish line, Minnesota’s Rocketman sounds fully content, like a man who has pursued his own oft-repeated credo at maximum velocity.

“If you can dream it, you can do it,” he says from his movie theater chair, surrounded by a house bursting with proof. “And another thing! If you don't quit, you can't be beat. That's kinda my deal.”