I got nothing against settling in with a long movie. Hell, I essentially ordered you out to Columbia Heights to watch all 179 minutes of Drive My Car last week. But like most pithily phrased maxims, Roger Ebert’s “No good movie is too long and no bad movie is short enough” is half-true at best. Plenty of good movies would be genuinely great with five or ten or minutes pruned away; plenty of mediocre movies are just one excess scene away from violating the Geneva Conventions.

Editing and pacing aren’t technical details—noticed or not, they’re essential components of what make a movie a movie. But maybe TV and home viewing have trained audiences to accept visual entertainment as an arhythmic barrage that we pause and resume at will, or the super-sized American mentality that more is always more has triumphed again. Either way, cinema sprawl is endemic, as blockbusters and awards-sponges alike habitually overstay their welcome.

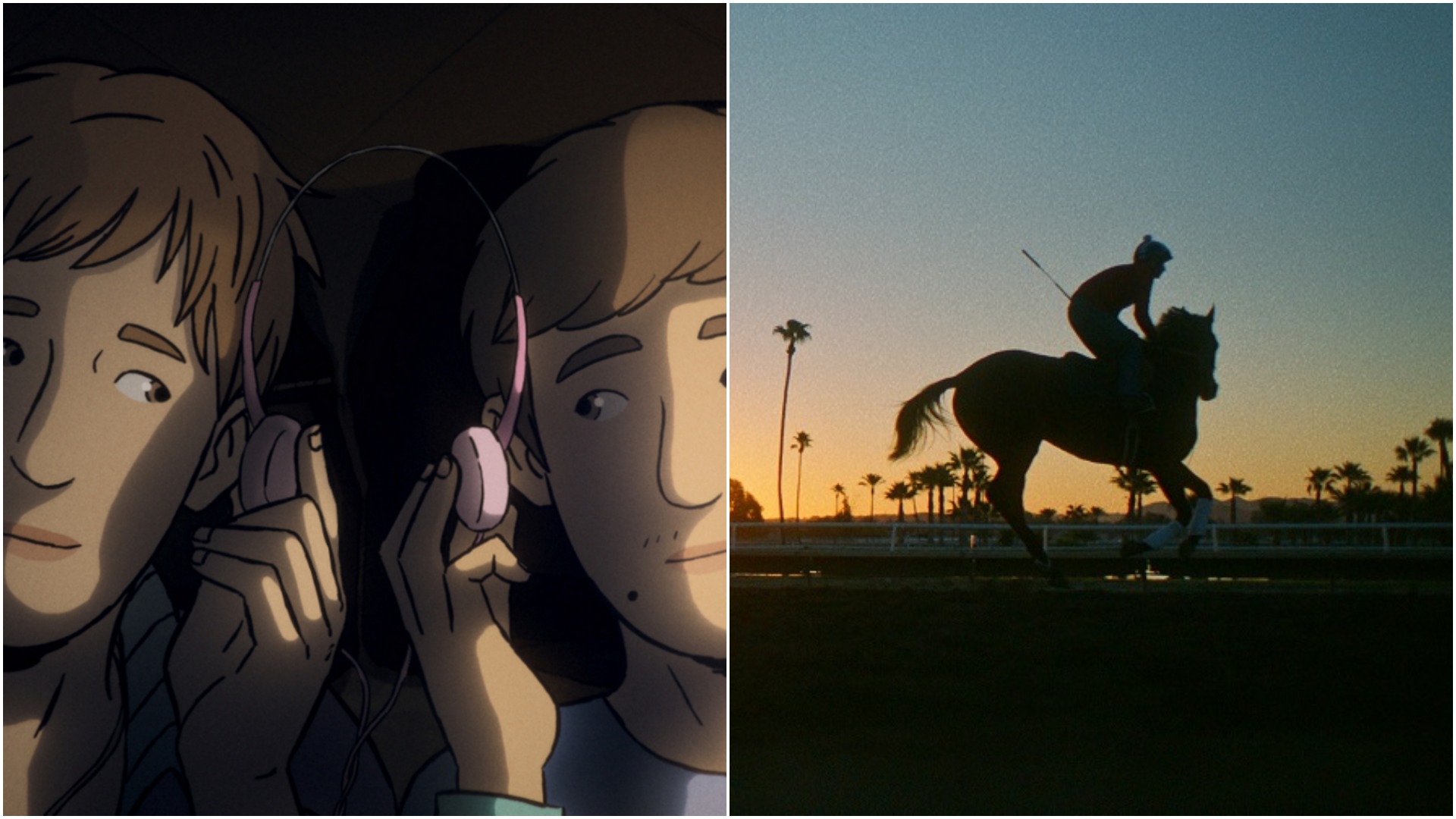

So let’s hear it for brevity. This week I happened to have enjoyed two movies that accomplish all they set out to in an hour and a half. OK, one is 89 minutes long and one is 94, ya sticklers, but still, they remind us that concision isn’t just a limitation—it’s an artistic challenge.

Befitting its name, Jockey is a small movie, as small as one man’s life. Clifton Collins Jr. is Jackson Silva [whispers to date: “that’s the jockey”], a taut, weathered fist of a guy who’s about one more fall from paralysis or death. Early in the film, we see him winning a race in a close-up, his face our total focus, the rest of the race dropping away as our concentration matches his. We watch as he realizes he’s won, and intensity passes to joy, and also when the adrenaline can no longer mask the pain, and his grin fades into a grimace. Not only has Silva constructed his identity around his trade, as so many of us do, but he’s come to need the narcotic high of the competition as well.

First-time director Clint Bentley is a jockey's son, and his film bores down with a determination to capture a subculture’s texture, rhythm, and language from the inside. It’s grounded in quasi-documentary moments where real-life riders discuss their craft and their injuries around campfire beers. These are people who live among horses and mud and perpetual physical discomfort of varying degrees and like-minded people they can speak to without undue explanation.

But for all its easy camaraderie and swapped war stories, Silva’s is not a world of confidantes and intimacy. His closest friend in the racing world is also the closest thing he has to a boss. Ruth Wilkes (Molly Parker) hires jockeys for horse owners, and as she watches Silva, her motivation to do what’s best for her wealthy clients and protect the best interests of an ailing friend overlap unevenly. Without being coy, the film is ambiguous about the possibility of a romantic attraction in a way anyone who’s experienced the proximity of a longterm friendship and a lack of other options will recognize.

When a talented younger racer named Gabriel (Moisés Arias) turns up, claiming to be Jackson’s son, the older jockey has his doubts. He mentors him regardless, belatedly realizing that by passing along what he’s learned he might age into a less physically demanding but no less meaningful role. But their relationship does not turn out that way.

Laid out baldly like this, Jockey ticks off all the plot points of a classic sports flick: the aging hero grasping for one more sliver of glory, the young upstart surpassing his idol. In some ways, god help us all, it’s Rocky V. But Jockey finds the humanity within the archetypes, less focused on winning or losing than devotion to craft.

Collins, an “oh that guy” actor finally getting his moment to shine, was the talk of Sundance a year ago. But he doesn’t oversell his performance, or worse yet undersell it with cloying dramatic understatement. Yes, he gets a wrenching seizure scene, and we watch him struggle to control his grip, but Collins captures a pain-wracked life without diving into awards-slavering disability porn. He moves the way this man would move, rather than showing us an imagined deviation from some hypothetically able “norm.” You’ll even quickly forget that he towers at an enormously unjockeylike five-foot-eight.

There are movies about dementia slowly creeping up on characters, or of extreme disability, acquired either via birth or accident, that must be risen above in a dramatically engaging (even scene-chewing) fashion. Less often do we see the slow process of feeling gradually failed by a body whose capabilities you’ve taken for granted. And while it may be as questionable to romanticize that breed of warped American manliness that proves its merit through quiet stoicism as is to celebrate its more extroverted and brutal counterpart, the fact that some men feel left with nothing more is worth acknowledging.

Adolpho Veloso’s cinematography captures the Phoenix landscape in a manner you might compare to Chloe Zhao collaborator Joshua James Richards's, but it’s less obtrusive, more casually observed. And what’s genuinely impressive is how it treats individuals as landscapes themselves. Jockey is a movie of shadowed expressions, of idiosyncratic faces backlit so their features emerge partially in unexpected shapes. Like the story and the characterizations, the images focus on detail. That makes Jockey the sort of movie you have to be careful not to oversell. Its value is its mundane, well-acted, well-constructed solidity. Like its characters, Jockey aims for accomplishment not greatness.

Flee is, like Jockey, the story of one man, but it’s told against a much broader historical and geographic backdrop. Danish director Jonas Poher Rasmussen illustrates the life of a childhood friend, who appears pseudonymously here as “Amin Nawabi,” through a distinctive start-stop animation style.

Another 2021 Sundance breakout (backed by producers Riz Ahmed and Nikolaj Coster-Waldau), Flee is largely a conversation between the filmmaker and the subject, who lays back as he recalls his past like he’s in an analyst’s office. And in some sense, he is, answering questions that lead him back through the lies that a supposedly humanitarian system forces refugees to tell to prove themselves deserving of their aid. Meanwhile, in the present day, we meet Amin’s boyfriend, a Dane named Kaspar who wants him to settle down in a home of their own. We know Amin survives. We just don’t know how he will decide to live.

Growing up, Amin is largely unaffected by (though not oblivious to) his country’s status as a Soviet puppet state. Things change once his father is disappeared by government officials, and his older brothers live in danger of being enlisted to battle the insurgent Mujahideen. These rebels take power (a decade later the Americans that funded them will become more familiar with them as the Taliban) and his family takes flight. Their far-from-safe haven is a post-Communist Russia of empty supermarkets, rampant inflation, and corrupt police—the sort of place that makes itself permeable to undocumented refugees because it knows how to exploit them.

The wrinkle in Amin's story, and a common enough wrinkle, is that he’s gay, a realization he comes to very young. We see him cutely ogling a kickboxing Van Damme and imagining a wink from his sister’s pop-star trading card. This desire is literally unspeakable—there’s no word for it in Afghan culture, he tells us—but aside from one chaste flirtation, it’s also brushed aside by more immediate concerns like the grim world of traffickers and police.

The animation style seems an affection at first, a way to lure jaded arthouse audiences into caring for yet one more culturally significant humanitarian tale. But it’s also an effective way of telling the story, its stylistic shifts registering different perceptions of memory. Occasionally, often in darker moments, the colors fade into charcoal sketches deliberately reminiscent of a-ha’s “Take on Me” video (we even see a carefree young Amin grooving to that Norwegian falsetto jam in ’80s Kabul), or Rasmussen cuts to clips of archival filmed footage, with the squared aspect ratio and rounded edges of a Super 8 home movie. And just on a rhythmic level, the visual stutters affect your perception over time—the world outside the Lagoon seemed shockingly fluid as I walked back to my car afterward.

Amin is a wonderful storyteller, as refugees have to be. They literally live or die by their narrative credibility. And our immersion in his tale means only afterward do we get a chance to gauge our relationship as listeners to the man whose words have entranced us. There’s no reason to distrust anything he says, but we might wonder how well we really know him, despite learning the most harrowing details of his life.

Audiences may not hear Flee as just one man’s story—to some, Amin will inevitably stand in for refugees, for Afghans, for gay men fleeing oppressive states. And the systems that threaten to crush the Amins of the world, and the humane systems that serve them at the cost of the truth, remain in place. Yet Amin’s success, as conveyed by Rasmussen, is in claiming a kind of individuality—his story, while not unique, remains his. We can celebrate one man’s escape from a world of unrelenting danger into the relatively ordinary anxieties of our own.

Jockey opens at the Lagoon tomorrow, January 28; Flee is already in area theaters.

Special Screenings This Week

Thursday, Jan. 27

Criss Cross (1949)

The Heights

This Burt Lancaster heist flick will make you jump! jump! $12. 7:30 p.m. More info here.

Trainspotting (1996)

Parkway Theater

Choo-choo-choose life. $9-$12. 8 p.m. More info here.

Film in the Cities: Radical Roots of Youth Media (2021)

Walker Art Center

An excerpt from a documentary on the youth-based revolutionary arts movement Film in the Cities, presented by the filmmakers. Free. 5-9 p.m. More info here.

Friday, Jan. 28

Filibus: The Mysterious Air Pirate (1915)

Trylon

Not to give away the mystery, but Fillibus is a woman! With piano accompaniment from the mysterious Katie Condon. $12. Friday-Saturday 7 p.m. Sunday 3 & 5 p.m. More info here.

Saturday, Jan. 29

Twilight (2008)

Alamo Drafthouse

Who knew one day Rob and Kristen would be the future of arthouse film? $10. 11 a.m. More info here.

Rigoletto (live)

AMC Rosedale 14/AMC Southdale 16/Showplace ICON at West End

Remember when they did a version of this on The Odd Couple? $25. 11:55 a.m. Wednesday 1 & 6:30 p.m. More info here.

La Région Centrale (1971)

Walker Art Center

Too warm for ya? Cool off with Michael Snow’s three-hour experimental film capturing a frigid Canadian landscape. Free. 7 p.m. More info here.

Sunday, Jan. 30

Inherent Vice (2014)

Alamo Drafthouse

Pynchon is filmable, turns out. $10. 6:30 p.m. More info here.

Koyaanisqatsi (1982)

Malcolm Yards

To honor Philip Glass’s 85th birthday, his experimental environmentalist collaboration will be projected on the United Crushers Mill. Pretty sweet. Part of the Great Northern Festival. Free. More info here.

Ride the Pink Horse (1947)

Trylon

You don’t have to tell me twice. Who wouldn’t ride a pink horse? $8. 7 p.m. Monday-Tuesday 7 & 9:15 p.m. More info here.

Tuesday, Feb. 1

Breaking Trail (2021)

Parkway Theater

A documentary about Emily Ford, the first woman and person of color to thru-hike the 1,200-mile Ice Age Trail in winter. She has a dog with her, if that seals the deal for you. $10. 7 p.m. More info here.

Summer of Soul (…Or, When The Revolution Could Not Be Televised) (2021)

Walker Art Center

Questlove’s unmissable (if overly talky) doc about the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival. Free for Walker members. 8 p.m. More info here.

Wednesday, Feb. 2

Groundhog Day (1993)

Alamo Drafthouse

Groundhog Day is a Groundhog Day movie. $10. 6:30 p.m. More info here.

In the Same Breath (2021)

Walker Art Center

Award-winning documentary about the Chinese and American responses to Covid. Free for Walker members. 6 p.m. More info here.

The Lost Daughter (2021)

Walker Art Center

Dakota Johnson looks so much like Kacey Musgraves in this. Free for Walker members. 8 p.m. More info here.

Opening This Week

Gamestop: Rise of the Players

Look, I still don't understand the stock market scene in Trading Places. No way am I gonna be able to follow this doc.

Ongoing in Local Theaters

American Underdog: The Kurt Warner Story

Belfast (see our review here)

Belle (see our review here)

Drive My Car (see our review here)

Ghostbusters: Afterlife (read our review here)

House of Gucci (read our review here)

The King’s Daughter

The King's Man

Licorice Pizza

Nightmare Alley (read our review here)

Parallel Mothers (read our review here)

Redeeming Love

Scream

Sing 2

Spider-Man: No Way Home

The 355

The Tiger Rising

The Tragedy of Macbeth (read our review here)

West Side Story (read our review here)