No two American cities look quite the same—they're molded by geography, by climate, by the era in which they're built. Industry determines the size and location of their factories and warehouses; factors like income and family size shape their housing stock.

And then there’s the work of sign painters, who, with neat hand lettering and flourishes of colorful paint and gold leaf, add their signature to the city’s visual identity. Hand-painted signs are part of the personality of a city. And in Minneapolis, buildings have historically had a lot of personality.

“Subconsciously, I think we took for granted the landscape of growing up in south Minneapolis, and how hand-painted it was,” says Forrest Wozniak. “This was a very hand-painted town.”

Wozniak is among the half-dozen or so sign painters still active locally today; you can find his work from the Blue Door Pub in Como to Lowry Hill Meats in Uptown to Angry Catfish Bicycle Shop in Standish. And his use of the past-tense there isn’t an accident—Minneapolis was a very hand-painted town.

America’s cities aren’t as strikingly different as they once were. Boring, mixed-use buildings, cheaply made, have very few differences from coast to coast, and much has been written about the increasing ubiquity of these bland and boxy new designs with their anodyne steel and glass.

Less has been written about the slow decline of hand-painted urban signage, though fascination endures about the ghostly vestiges from its heyday. Juxtaposed against the lifelessness of new construction, the colorful, character-filled marquees—even ones that were painted recently—can feel like relics from another time. But the few remaining sign painters in Minneapolis will tell you: They’re not going anywhere yet.

Phil Vandervaart shuffles around his south Minneapolis kitchen, putting on the kettle for tea as bluegrass fuzzes out of an old radio. We head out to his garage workshop, where lettering sketches sit neatly on an easel and nearly every visible surface is splashed in paint.

“My sign painting history, my whole bread and butter is storefronts,” he says. “I mean, I do other stuff, but now, as I’m getting older… that’s really all I want to do.”

Vandervaart moved to Minneapolis in 1983, on his 30th birthday; he’ll turn 70 this July. He’s owned the house on Minnehaha he now occupies since ’95—maybe you’ve noticed it, it’s the one that always has the yellow board advertising “Handpainted Signs” out front. Before that, he lived out of various storefronts and warehouse spaces during jobs. (“I’m one of those guys,” he chuckles.)

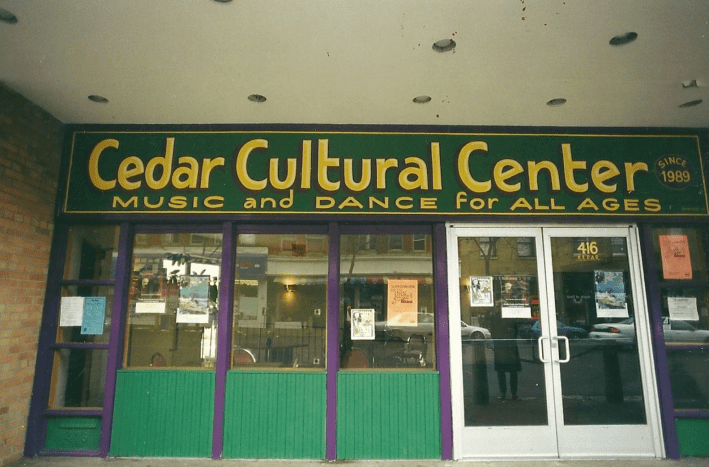

In the 40 years that he’s lived in Minneapolis, Vandervaart has painted signs all over the city, and a few in St. Paul. “My whole life has been painting signs in this town,” he says. You’ll find the highest concentration of his work decorating the West Bank: Palmer’s Bar, the Cedar Cultural Center, Hard Times Cafe, Midwest Mountaineering, The Wienery. “The Hard Times, I did that 30 years ago,” he smiles, reflecting on its checkerboard lettering and tropical backsplash.

Born in Holland, Vandervaart grew up in a small town in Indiana, where he and his six siblings attended an “oppressive” Catholic school. He spent the ’70s hitchhiking from Chicago to San Francisco, was briefly involved in “some cultish stuff,” and eventually landed a job driving school buses, which he’d wash on weekends for extra cash. That’s when he saw a guy painting the buses: “He was moving just about as fast as I was, and he was getting 50 bucks a bus.” Vandervaart took a sign-painting class through a Carter-era Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) work program, for which he got paid—not much, he estimates it was 60 bucks a week or so—and started to hone his craft.

Vandervaart has painted some of the city’s most iconic and well-loved small businesses, venues, bars, and restaurants, both past and present. Jax Cafe. The 400 Bar. Hymie’s. The orange juice-hued block letters at May Day Cafe. The playful mustard-yellow lettering at Kramarczuk's. In his own neighborhood alone, he painted the technicolor facade at Moon Palace Books and the stately black and white walls at The Trylon. And for every household name, there are a dozen more neighborhood grocers, auto shops, laundromats, and hardware stores adorned with Vandervaart’s work.

Forrest Wozniak got his start in a similarly freewheeling way. A child of south Minneapolis, by the late ’90s he was working construction and handyman jobs. In his free time, he and his friends would find rusty old objects—gas cans and the like—and paint on them. “It was the late ’90s, right? You can picture the aesthetic,” he chuckles. They’d hitchhike, ride freight trains, and drive around in barely working Chevy Novas. Old south Minneapolis stuff.

Wozniak and his friends quickly realized how easy it was to travel with a painter’s kit. “This looks like a big, industrial operation,” he says, gesturing around his Minneapolis shop, which is situated in an alley off 41st Street. “But if you stripped it down, you could have some brushes, red, white, and black. Get paint thinner at the hardware store in the town that you were in, and you could paint signs in Gerlach, Nevada for the price of a six-pack of tall cans and a hotel room.”

After some time on the road, “operating on tremendous amounts of ego and no skill,” Wozniak moved back to south Minneapolis, where he’d meet Vandervaart. The two had a lot in common—working-class virtues, blue-collar backgrounds. “Growing up on the West Bank, it supersedes age barriers. People just know each other,” Wozniak says.

Friends of Wozniak's had purchased May Day Cafe, where Vandervaart painted the original sign, and asked him to paint a new one. Wozniak took some examples of his work to Vandervaart, who, he recalls, replied fairly straightforwardly that they were ugly. But he asked the younger painter to come by his shop.

Thus, Wozniak’s “modern day apprenticeship” began. It was more of a partnership, really—this wasn’t the first time Vandervaart had been approached by a young person who wanted to learn his trade. “Forrest did something that none of the other people did: He brought work in,” Vandervaart recalls. Wozniak would approach a potential client, Vandervaart would draft up the patterns and guide him in the painting, and they’d split the profits.

“I think we went 17 years straight painting a sign together in some capacity,” Wozniak says. Together, they painted signs from the Fitzgerald Theater to Springboard for the Arts to Dusty’s Bar to South High.

Sometimes they’d remember to take a picture after; plenty of other times, they didn’t have a camera on them.

“You really did sell yourself; I mean you literally went around with a portfolio you’d developed in a book and you walked up to storefronts and really sold them on what you can do,” Wozniak laughs. “There were so many small businesses. Whole strips of small businesses.”

That was then. As mom-and-pop shops have disappeared, so too have the potential clients for independent sign painters like Vandervaart and Wozniak—both of whom view their work as a quietly radical act.

Sign painting has historically been important for all people, across socioeconomic backgrounds, but Wozniak notes that’s especially true for folks who have less. It’s why he’s always been willing to work cheaply for people who need it, and why Vandervaart has done jobs on a trade basis when that’s more convenient. He somewhat famously painted the Hard Times Cafe sign in exchange for a lifetime of free coffee.

Being born and raised in south Minneapolis, as Wozniak was, or spending 40 years here, as Vandervaart has, means that the two are acutely attuned to changes in the city. Both say that politics informed their work during their earliest painting projects, and continue to today.

Vandervaart is disappointed to see Minneapolis turn into just another city where young people can’t afford a house. “The city does nothing to help young people. Zero. They’re catering to the corporations,” he grumbles. In between his musings on sign painting, Vandervaart, who still rides his bike all year round, at various points shares his views on hypocrisy in the Republican party, abortion rights, and the “cheaply made,” “disposable” buildings that are going up around the city. (At one point, we even get to Reagan’s meddling in Central America, and the under-recognized successes of the Sandinistas.)

As for whether he’s willing to paint new constructions (“chipboard-formaldehyde horror shows”) for property agencies (“housing cartels”)? “I refuse,” Vandervaart says. You can take a guess how he feels about pro-biz Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey, along with the “immoral” landlords who let their buildings sit empty rather than renting to a small business owner in the neighborhood.

“It’s not just starter homes, it’s starter storefronts,” he says. “I’ve heard 40 years of horror stories of the city of Minneapolis suppressing these people.”

But these sign painters know that they’ve been lucky, too. Now 41, Wozniak was able to paint his way into homeownership; he raised his two daughters on the money he made painting signs. And it’s the people of Minneapolis, not politicians or developers, who made that possible.

“This city gets a lot of shit because it’s going through the massive growing pains of social engineering,” he says. “For all of us that are from here, just regular folks, it’s hard to compliment the city. But this city has been a host for my success, and I do not take that for granted.”

“This city has been a host to art,” he continues. “I understand that we are fortunate to have lived in a little bit of a land of make believe… I think that’s a testament to the character of this city.”

There’s an old joke Wozniak heard when his career was just starting out: “Sign painting is the second-oldest profession.” (You know what the first-oldest is, right?)

If the painters sound nostalgic when they talk about the craft, well frankly, that’s because they are. Line a Depression-era photo of a sign painter on a scaffold up against a photo of Wozniak painting the brick exterior of a bike shop today, and you’d find more similarities between the two than you would differences.

Dan Madsen of Dusty Signs is a third-generation sign painter, following in the brushstrokes of his great-grandfather and grandfather (the sign-painting gene skipped one generation).

After inheriting his grandfather’s old sign painting stuff—books, brushes, photographs—Madsen fell in love with the craft, eventually apprenticing with prolific sign painter Derek McDonald out in Berkeley, California. (Though his introduction to sign painting came a bit after Wozniak and Vandervaart, his story shares similar hallmarks: Madsen worked with McDonald, tagging along on jobs and sleeping on the floor of his shop, trying to soak up as much knowledge as possible.) He’s been painting for roughly a dozen years as Dusty Signs.

While Madsen laughs that he tries not to get too romantic about hand-painted signs—“We’re not curing cancer or saving the world,” he quips—it’s also kind of hard for him not to. There’s just something more tactile, more familiar, more human about them than the computer-generated and printed vinyl lettering that rose to prominence after the vinyl plotter was invented in the early ’80s.

“You’re more open to do whatever the pencil can draw,” Madsen says. “The hand touch of it, I think, is just a little more relatable, or approachable, or even just desirable. I think people can notice… when something is different or original or hand-done versus something you might see every day in a strip mall.”

“And you know, no two signs are the same—even if you tried to paint them the same, there’s subtle differences,” he adds. “They kind of live their own life. They’re their own thing.”

Like all things that are made by hand, there are limitations, of course—it’s a slower and more methodical process. Vinyl decals are often cheaper to produce, and it’s easier to go to a website than to track down “a weird dude in his garage,” as Wozniak laughs.

As for whether the art of sign painting is “dying,” as many have reported it is? “It’s a great question, and a complex question,” Wozniak says. He notes that of course, it’s died to a degree, because in the days before vinyl lettering, a midsize city could support multiple sign shops that staffed 50 sign painters apiece. There was a time that everything from stop signs to gas station pumps were hand-painted, and that’s just not the case anymore.

But sitting at his kitchen table as Vandervaart scrolls through his camera roll looking for a photo of a garage he painted recently, it’s hard to imagine that sign painting is dead, or could ever die. In the last few years alone, interspersed with photos of his grandkids playing on their farm (“they jump on pigs, you know?”) are photos of signs he painted for Roadrunner Records on Nicollet Avenue, for Hawkins Automotive just down the road, for Tamu Grill (briefly Kilimanjaro Grill, the sign for which he also painted) in Cedar-Riverside. There’s the red-and-white sign he did for the still-in-the-works D’s Banh Mi, updated work for Modern Times, the recently reimagined signage at Hard Times Cafe, a new logo for the Hook & Ladder Theater.

“Minneapolis is not a huge city, but it’s big enough where it’s able to keep… I don’t know, three to five sign painters busy full time,” Madsen says. He’s done everything from big exterior projects—Blackstack Brewing, Bauhaus Brew Labs, the building-enveloping block letters at the new Eat Street Crossing—to delicate gold leaf applications like what you’ll find at Spyhouse Coffee or at Boludo’s expanding pizza empire.

There are plenty of people, still, who value the time-honored (and, yes, time-consuming) tradition of sign painting, and who believe, as the painters themselves do, that this outdated art form offers an eye-catching quality that’s worth the effort.

“Less is more, sometimes,” Madsen says. “Or less is enough.”