Bob Samuelson first visited Palmer’s Bar in the winter of 1983, or maybe it was ’84, after hearing about it from his older brother.

“There was this sort of intellectual aspect, a salon atmosphere in the French sense,” recalls Samuelson, now 62 and living in Stillwater. “What other kind of bar would have a fat guy in overalls drinking Hamm’s on a Tuesday who can tell you about the Upanishads?”

After joining the crew the way most people did (by hanging out at the bar long enough) Samuelson worked as a bouncer from 1988 to 1991 before returning to school to become a physical therapist. In 2009, he started intermittently filling in shifts again, sliding into a recurring role he holds to this day. He spent countless hours in the 119-year-old Minneapolis bar over the years, but May 3, 1986, is by far his favorite day.

Samuelson had wondered for a while how to approach this striking woman he noticed on the West Bank. He’d see her at Palmer’s or the 400 Bar, but she was always with a group of friends. He’d see her work her overnight shift at the Riverside Cafe.

May 3 was the Kentucky Derby. After a party at a friend's losing bets and drinking mint juleps, he stopped by Palmer’s, asked another friend if she had any weed. She didn’t, but her friend, Mary Alice, did.

“She taps her friend on the shoulder and it’s the same woman I’d seen around the neighborhood for some time,” Samuelson says. “I’m like, boom, this is my chance. And that’s how we met.”

This year, they celebrated their 34th wedding anniversary.

Defining what Palmer’s is to those who know it best is an exercise in futility. It’s easy to think the bar, closing September 14, is just a bar, no different than the dozens of others that have closed in the past five years.

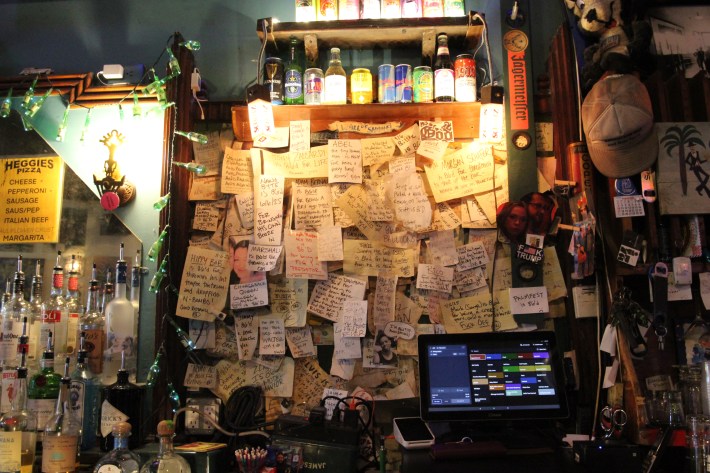

But Palmer’s is a part of Twin Cities history. It’s where Bonnie Raitt did crossword puzzles with Spider John Koerner while crafting her self-titled debut album in 1971. Koerner, one third of the folk-blues trio Koerner, Ray & Glover, may as well have paid property taxes at the end of the bar. Cornbread Harris still electrifies crowds each Sunday on the piano at 98 years old.

Esquire named Palmer’s one of the top bars in America in 2014. Jon Hamm stopped by in 2022 after missing his flight. In the 1990 movie Old Explorers, Palmer’s is where an elderly José Ferrer and James Whitmore craft a fantasy plan to find the Fountain of Youth in the Yucatán, peppering the conversation with references to “Indian blowdarts” and traveler’s diarrhea. In Factotum, Matt Dillon, playing Charles Bukowski's self-important alter ego Hank Chinaski, finds Lili Taylor's Jan at Palmer’s after an argument before assaulting her.

The history of Palmer’s is well-documented, but it’s the everyday occurrences that make the bar an irreplaceable part of Minneapolis. It's where Redboi McBride grew up, playing pinball as a toddler. It’s where Ben Noble had both his wedding and his baby shower. It’s where Aaron Colgrove almost pulled out a guy’s tooth on the patio. It’s where, quite recently, I went when I was unceremoniously laid off by the University of Minnesota’s Hubbard School of Journalism and Mass Communication.

That is the unwritten history of Palmer’s, a place of radical acceptance with an energy that’s hard to quantify or even qualify.

Money is the simple answer to how a Twin Cities icon ended up flaming out. No single factor or decision led to its demise. Rather, catastrophic mismanagement, struggles in the bar industry, changes in how people socialize, and a neighborhood that’s evolved from what it was 50 years ago all played their parts.

Here’s how an institution died.

The Silent Partners

About a week before the July 2 public post announcing Palmer’s closure, owner Sarah Dwyer broke the news to the staff. But there had been rumblings for some time.

“I didn’t want to just lock the door and put a sign on or be like ‘guess what, we’re closing’ and not give them any time to find other jobs or have time to say goodbye to regulars,” Dwyer said through tears back in July. “At this point, I don’t even know if we’re going to make it to the end, but I hope we will.”

The bar has struggled for years, sometimes publicly. Former co-owner Tony Zaccardi (who did not respond to multiple interview requests) has shouldered most of the blame. The truth, Dwyer says, is a bit more complex.

Pat and Sarah Dwyer’s love story started at Palmer’s. The two met for their first date in 1990 before heading to Theatre of the Round to see Chekhov’s Three Sisters.

Pat spent loads of time on the West Bank, bouncing between venues and working for Freewheel Bike. He and a business partner opened Grumpy’s Bar in northeast Minneapolis in 1998.

Pat hired Zaccardi at Grumpy’s, where the local musician worked for 18 years, rising to general manager. Zaccardi had handled the bar well, so when Palmer’s went up for sale in 2018, partnering with him on one of Minneapolis’s most-established bars seemed like a no-brainer.

The Star Tribune story about the sale enthusiastically touted the involvement of Zaccardi, who was popular and known throughout the Minneapolis music scene. Pat and Sarah viewed it as a way to reward their longtime, loyal employee. In the Strib writeup, Zaccardi made one fateful proclamation: "It's Palmer's. I'm not going to screw it up."

Publicly, Palmer’s seemed in a good spot.

But the chaos started almost immediately, according to staff at the time. Zaccardi’s behavior was erratic, and some of his decisions, such as purchasing dozens of broken neon signs, were puzzling.

“He was a mess,” says Lenn Burnett, one of Zaccardi's first hires who worked security, cleaned up the bar, and sometimes hung out with Zaccardi during off-hours. “Someone would come up and ask something like if he got an email and he’d fly off the handle just throwing shit. You never knew what you got.”

Emily Jacobsen, Palmer’s current manager, joined the team as a bartender in 2017.

“When [Tony] first bought the bar, he wanted to fire all the staff and staff it with his friends and girls he wanted to fuck,” she says.

Jacobsen convinced Zaccardi that was a bad idea and would alienate the loyal customer base, many of whom view the bartenders as family.

“He would throw shit. He would break shit. He wouldn’t listen to you. He didn’t communicate well,” Jacobsen recalls. “He didn’t get it at all, and he expected things to just get done miraculously without telling anybody or paying anybody or doing anything himself, which was frustrating.”

There was also the drinking and cocaine use, which Zaccardi acknowledged in a January video about his sobriety for the City of Minneapolis Health Department, where he currently works as a public health specialist. Not to mention the untold sum Zaccardi lost on pull tabs.

“The gambling was like, whoa,” Burnett says. “You’re up $1,500. Let’s quit and go somewhere else. He’d sit and go up $2,500 or $3,500. He wouldn’t leave until he lost it all.”

Still, money kept flowing and deliveries kept coming in, so staff didn’t think much of it. Bartending at Palmer’s was a lucrative gig and there didn’t seem to be more pressing issues beyond Zaccardi being, as Jacobsen put it, an “asshole.”

Then the pandemic hit. The already thin margins at bars like Palmer’s evaporated overnight. During the unrest following George Floyd’s murder, Zaccardi appeared frequently in the news as a Black business owner.

Zaccardi received hundreds of thousands of dollars in grants, ostensibly to help the bar and repair the building, including more than $340,000 from the Small Business Administration, more than $165,000 in forgiven PPP loans, and a $10,000 grant from the NAACP to support Black-owned venues. Another $22,000 came from a fundraiser organized by a regular.

But the fiscal mismanagement ran deep by that point: Daily deposits weren’t going to the bank; taxes weren’t paid; and the bar ended up on the delinquent tax list, meaning they could not purchase liquor from distributors. Zaccardi wrote checks from Palmer’s to cover his gambling debts, according to the Dwyers, and he spent $14,000 at Home Depot that wasn’t for the bar. He had multiple storage units (for what, the Dwyers don’t know).

The exact total amount Zaccardi took from the business is unknown. In a 2023 divorce filing, Zaccardi’s now-ex wife said he took nearly $380,000 out of Palmer’s accounts without her knowledge.

Sarah Dwyer says she first found out about the missing money in August 2022. Zaccardi had not filed the previous year’s taxes and the extension deadline loomed. When she offered to help with the books, she discovered at least $278,000 in missing funds.

“I’m glad he’s alive. For a while there, that didn’t look like it was going to be the case,” Pat Dwyer says. “But the partnership had to be dissolved because Palmer’s was put into a position that we’re still recovering from.”

If These Walls Could Talk

In the 1850s the federal government granted the land on which Palmer’s now sits to Isaac Atwater. A settler and lawyer who served as Hennepin County attorney and one of the state's first elected supreme court justices, Atwater was also a member of the first University of Minnesota Board of Regents and editor of the St. Anthony Express, one of the state's oldest newspapers.

The Minneapolis Brewing Co., the predecessor to Grain Belt, bought the space in 1906 and opened Carl’s Bar. The bar survived Prohibition, and rumors circulated that it was a speakeasy with a tunnel connecting it to the neighboring 5 Corners Saloon—a legend somewhat backed up by its spacious basement. The upstairs served as a brothel in the 1930s, and a corset found during renovations is currently displayed in a lightbox on the wall.

In 1950, Henry Palmer renamed the joint Palmer’s Bar. As the activist hippie movement swelled on the West Bank through the 1960s, Palmer’s became a countercultural gathering place. In the 1970s, during the development of the Riverside Towers, community pushback halted a planned bridge that would have erased it from existence.

It was in these decades that Palmer’s earned its reputation as a meeting spot for the culturally rich West Bank. Other bars had music, but Palmer’s was a must-stop for a menagerie of patrons: hippies, anti-war activists, the LGBTQ+ community, building and trade workers, musicians, artists, and college students from Augsburg University and the University of Minnesota.

But most importantly, Palmer’s was known for its vibes. All were welcome as long as you were up for a good time and followed the golden rule: Don’t be a dick.

MJ Mueller remembers those days fondly. She first moved to the neighborhood in the late 1960s and estimates that the first time she went to Palmer’s, she was 19.

“When I lived there, it was basically populated by hippies of many different colors and stripes,” says Mueller, now a retired financial professional. “A lot of the older homes were occupied by hippies, many of whom worked in the neighborhood. Men, especially, worked in the trades.”

Mueller made her life on the West Bank. She worked at the Riverside Cafe where she met her husband, musician and producer Dave Ray. She was a mainstay in the West Bank’s vibrant music scene, such as the Pilot’s Club (which would later become the Triple Rock) and the 400 Bar. And, of course, there was always Palmer’s.

“The daytime had a lot of the old people population and oftentimes people from the trades would go in there to have a beer to steady their nerves because they’d been drinking the day before,” Mueller says. “I knew a lot of roofers who started their day at Palmer's before going to their job.”

Palmer’s also became a refuge for the odd, a characteristic it’s maintained to the bitter end. As evidence, Mueller points to the Minneapolis Battle of the Jug Bands, which began back when she was new to the neighborhood.

“And it was only maybe four bands,” Mueller says. “They kept trading personnel between each other. It was just raucous. It was hilarious because they were all trying to outdo each other with crazy songs.”

This informal contest became an annual event, one Mueller helped run for years. It’s now held nearby at the Cabooze, with a pre-battle party at Palmer’s.

“You could be pretty much anything at Palmer’s,” Mueller says. “Or do anything… within reason.”

While Redboi McBride remembers the raucous times as a bartender and bouncer starting in 2000, his Palmer’s origin story started in infancy.

“I was raised in Palmer’s. Literally,” McBride says. “My parents started taking me there when I was a baby. When I was a toddler, I’d go in there with my dad and play pinball. I learned how to play pool there. All my neighborhood aunties and uncles were there. Florence, who owned the bar for like a million years, was like a grandmother to me.”

In those years Palmer’s also gained its cultural reputation. Spider John was a figure in the bar for 50 years (to the point his New York Times subscription was delivered there) and musicians, such as his mentee, Raitt, would often stop through for a Palmer’s pour, the stiffest and cheapest in the city.

“I have loved hanging out with John at Palmer’s over the many decades,” Raitt says via email. “For me… Palmer's is part of the iconic and treasured history of Minneapolis's historic West Bank scene. I can’t even imagine John without picturing him perched atop his stool at his home haunt… We'll miss you, Palmer's.”

The Palmer’s Poor

Sarah Dwyer quickly took over Palmer’s in August 2022 once she realized how much money Zaccardi had taken from the bar. Employees describe it as a time to rally to save Palmer’s.

The Dwyers plunged their savings into the bar to try and stave off the worst. They plowed in $80,000 right away to get off the delinquent tax list and make payroll.

“Tony was just spending money on ridiculous stuff,” Sarah says. “I thought once I shut that off, things would get better.”

Over the next three years, they put in another $300,000.

The bar industry, in general, is in a precarious spot. And the culprit is obvious: People are drinking a lot less, especially younger people. Palmer’s attempted to attract crowds with live music nearly every night of the week, but those efforts come with their own costs.

An indoor weeknight show without a cover charge can be relatively cheap: around $500, Sarah says. If that show needs a sound engineer and a door person, the cost rises to around $800. A weekend show on the patio with a cover charge in need of sound, light, and door crew runs much more.

The commitment to live music costs as much as $20,000 a month. Palmer’s keeps 20% of the door, which Sarah says never covers cost. The bar still relies on drink sales, and those receipts were never enough after she took over.

With payroll, taxes, insurance, purchases, and permitting, Palmer’s takes around $95,000 a month to run—even more in the summer, Sarah says. That climbs even higher if something breaks, which happens frequently in a building that’s more than a century old.

In June, Palmer’s brought in $60,000—and that, says Sarah, was a good month. Business is much slower in winter. Still, Sarah was optimistic in 2023. Sales were better than the year before. “I thought in two or three years, we’d be in the black and eventually get paid back,” she says.

The feeling ended by April 2024 when revenue declined yet again. Live shows posted healthy attendance figures, but people weren’t buying drinks.

“Our daytime business dried up. Those old timers either stopped drinking or they’re dying off,” Sarah says. “Spider John [who died in May 2024] would come in every day, he’d attract four or five people. It started to become where we don’t really have any weekday business. It costs us money to be open during the week.”

Checks bounced. The bar ended up back on the delinquent liquor tax list.

The inevitable was rapidly approaching. The idea of a fundraising campaign wasn’t feasible to Sarah, who viewed it as a temporary solution to the ongoing problem.

Changing Neighborhood

Sarah and other venue owners in Cedar-Riverside sought Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey’s help with their crumbling buildings through the West Bank Business Association.

“We all went to the mayor with this issue to see if there were any funds to help with this issue to maintain our buildings,” Sarah says. “The answer was, ‘I can’t help you. There’s no money. You should get a lobbyist and go to the state and get it on a budget in the future.’”

Ask any of the regulars at Palmer’s Bar and they’ll tell you the neighborhood has changed.

On paper, Cedar-Riverside seems a perfect location for investment and development. Situated next to downtown, it has access to both Blue and Green line trains as well as interstates 35W and 94 and multiple bike paths. Two universities call it home. And it had a reputation as one of the hippest neighborhoods in America.

It’s been a diverse community for decades. Through the late 1800s and early 1900s, Eastern European and Scandinavian immigrants dominated the landscape. East Asian immigrants came through in the 1980s.

Yet the arrival of Somali and other East African immigrants in the 1990s created a predicament for the once-bustling bar scene: The primarily Muslim population does not drink. Concurrently, the hippies of the old West Bank have either moved or died off. The neighborhood bar no longer represents the neighborhood.

Factor in crime, drug addiction, and homelessness. The doorway next to Palmer’s is a frequently used drug haven. The bus stop outside the bar smells of crack. A regular at Palmer’s earlier this year had to apply a tourniquet to a man after a stabbing.

While reporting this story, I walked outside to find a woman running down the middle of Cedar Avenue screaming for Narcan. After Sarah pointed her to the Narcan station outside Palmer’s patio gate, I ran down the street to help with a man who’d stopped breathing. He eventually sprung back to life after a good samaritan administered the Narcan and CPR while I called the ambulance.

Staff and regulars, while lamenting the changes to the neighborhood, are quick to shoot down any blame to the immigrant population. Palmer’s does not have a monopoly on the West Bank and it wasn’t the East Africans who stopped coming to the bar, but rather white patrons who began avoiding the neighborhood.

Sarah wrote to Frey twice, asking for more enforcement of city code to help clean up the neighborhood. Both letters went unanswered, she says.

A Love Story

January 5, 2021, was Ben and Shelby Noble’s first date at Palmer’s. Shelby, a 31-year-old mail carrier, kept giving Ben, a 47-year-old arbitration investigator for city mail carriers, little fist bumps as an excuse to touch him as they discussed union matters. The spark was immediate.

October 16, 2023, was their first week off in a long time. As the date neared, Shelby suggested they get married. She bought a dress and went to the courthouse. They wed in front of the judge, who happened to be a Palmer’s regular, and were done by 5:30 p.m.

The next stop, naturally, was Palmer’s for a drink with Shelby’s dad and Ben’s brother. One drink turned to two. Which turned to three. Which turned into a full on reception that lasted the entire night.

“We just showed up with no intention of having a party and had a massive party,” Ben says.

Nine days later, the couple got a surprise: Shelby was pregnant. They planned now 14-month-old Emerson Eagle’s baby shower with only one spot in mind.

“This was the only place,” Ben says. “Why would I go anywhere else to hang out? If I’m going to go somewhere, I want to give Palmer’s my time and attention.”

Palmer’s is family, a sentiment echoed by the more than two-dozen staff and regulars interviewed for this story. If someone is gone for too long, people take notice.

The staff is especially tight-knit. When Lenn Burnett’s heart failed, requiring hospitalization and a pump, his Palmer’s family showed up at the hospital. They take trips together and meet up for each other’s birthdays. As the bar struggled, many of them felt like a relative was struggling. Some of them quit using their employee discount.

“This is the most familial place I’ve worked in 20 years of bartending,” manager Emily Jacobsen says.

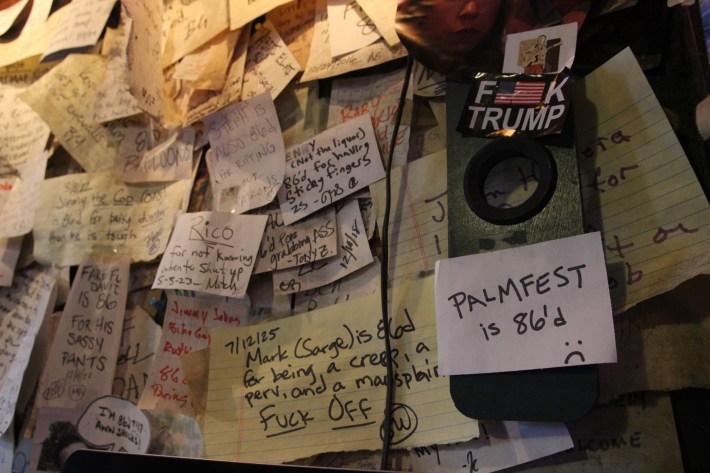

Palmer’s commands respect—and anyone who didn’t respect the bar found their name displayed on the “Wall of Shame” along with everyone else who’d been 86’d. Aaron Colgrove, a 42-year-old bartender who started coming with his fake ID as a teenager, likens it to a DMZ of sorts.

“This has always been a neutral zone for every walk of life,” Aaron says. “So the people here are like, ‘No, no, no, don’t fuck around here. Fuck around elsewhere.’ It’s like the watering hole where everyone can come together and be fine.”

Others liken it to a cosmic entity that transcends the business or the building.

“To me, this place almost feels like a spiritual vortex,” says Brian Herb, a sound engineer and roadie who first started frequenting Palmer’s 30 years ago. “There’s a lot of energy around this place and, to me, it’s all positive. People from all different walks of life come in here and just chill.”

Tony Paul, a KFAI radio host known as the “Mayor of the West Bank,” says the bar has both a literal and figurative intoxicating effect on people who walk through its doors.

“Once you start coming in, you come a few times, and it grabs you,” he says. “It’s not that easy to leave. Some people even quit drinking and all that stuff and still come back.”

If there’s a place it will hold in Twin Cities lore, it is one of radical acceptance. All were welcome.

“It’s a place to be yourself and it’s a place to let everyone be themself,” explains Ben Marker, a 43-year-old bartender who says he felt somewhat isolated after moving from Lincoln, Nebraska, until he found the West Bank and Palmer’s. “It’s not even a matter of coming in and letting your hair down. We don’t ever really have to have our guard up. This is where the freaks hang out. Here, we don’t think you’re freaky. You’re just one of us.”

86’d for Life

As the financial walls closed in, Pat and Sarah tried to find a buyer. But everyone they reached out to in the bar, music, service, and entertainment sectors gave them the same answer: hard pass. Still, they resisted contacting developers, saving Palmer’s from the fate of so many other once-treasured spaces that had become soulless condos. (They purchased the building for $475,000 in 2018.)

The Dwyers eventually reached a deal with Dar Al-Hijrah mosque, with which Palmer’s shares a wall. Dar Al-Hijrah leadership plans to turn the bar into a community space—which, in a certain way, can be seen as a continuation of Palmer’s legacy. (A representative from the mosque did not respond to multiple requests for an interview.)

Sarah understands the anger and confusion many who love the bar feel, but stressed there’s no single reason for the bar’s closure.

Two months after the announcement, Sarah sat at the end of the bar on a busier-than-normal Monday afternoon. This time, tears didn’t immediately start streaming as we spoke (though they did make an appearance).

“It’s still upsetting, but I’m not as upset,” she says.

The somewhat cruel irony is that business has never been better. Mondays used to pull in about $500. That’s up to $3,000. Sundays with Cornbread Harris were once somewhat mellow affairs that brought in about $1,200. Now it’s the busiest day of the week, netting around $7,000, forcing staff to re-route patrons from the front door to the patio.

“It’s been crazy busy, which kind of makes me mad,” Sarah says. “Honestly, if it’d been like this the entire time, we wouldn’t have any trouble. It’s just what happens when a place starts closing.”

She adds with a laugh, “I might even be able to pay the property tax.”

The history that adorns the walls is being claimed as the end nears. Sarah had to take some of the original photos and posters down after a couple pilfered a photo in the days after the announcement. They were publicly shamed into returning it, but Sarah thought it best to remove them for posterity and provide prints for sale.

Staff and regulars have had first dibs on keepsakes. The pictures on the Wall of Legends of the old-timers who have died are being reunited with their families’ where possible. More historic fare is going to museums and other venues. Spider John’s guitar will go to the Cedar Cultural Center. The piano Cornbread plays weekly, which once belonged to famed songwriter and producer Willie Murphy, will have a new home at Hook and Ladder. The owners are in discussion with the Minnesota Historical Society to take the wooden Palmer’s man that sits outside the bar.

Zaccardi has kept a low profile since the announcement. Sarah Dwyer says they considered suing him to recoup the missing funds, but were talked out of it by a lawyer.

“They just told us it was going to cost this much money and you’re not going to get this money back if we do this because he doesn’t have it. It’s gone,” she says.

The staff has planned their exit where possible. Most had other jobs they planned to focus on, such as Aaron Colgrave’s restaurant gig or Bob Samuelson’s physical therapy. Emily Jacobsen was recently hired at Grumpy’s.

“Having been even a small part of this place’s history will be one of the great things of my life,” Marker says. “I also try to keep it into perspective that everything is a small fucking blip and that it only matters to the people who know about this place.”

The regulars have been more melancholy about the future. Palmer’s closing isn’t just the end of their hangout spot, but the end of the West Bank they once knew. The counterculture is gone.

“As fewer and fewer places are open, the West Bank becomes less of a destination,” Brian Herb says. “Maybe some of the other bars in the neighborhood soak up that business, but then eventually it dries up to a point and here we are.”

Brooke Beckman, who was born down the street from Palmer’s and began working behind the bar in 2003, was more optimistic. After all, a bar is just a bar. A community is much more.

“This community is going to transcend these walls,” she says. “It does transcend these walls. And it’s going to be just fine. We’ll be OK.”

Palmer's last day open is September 14 and features a slew of bands who have played throughout the years. Doors open at 10:30 a.m. with the Front Porch Swingin' Liquor Pigs starting at 11 a.m. Cornbread Harris will close out the night starting at 9:15 p.m. and Palmer's closing for the last time at 11 p.m.