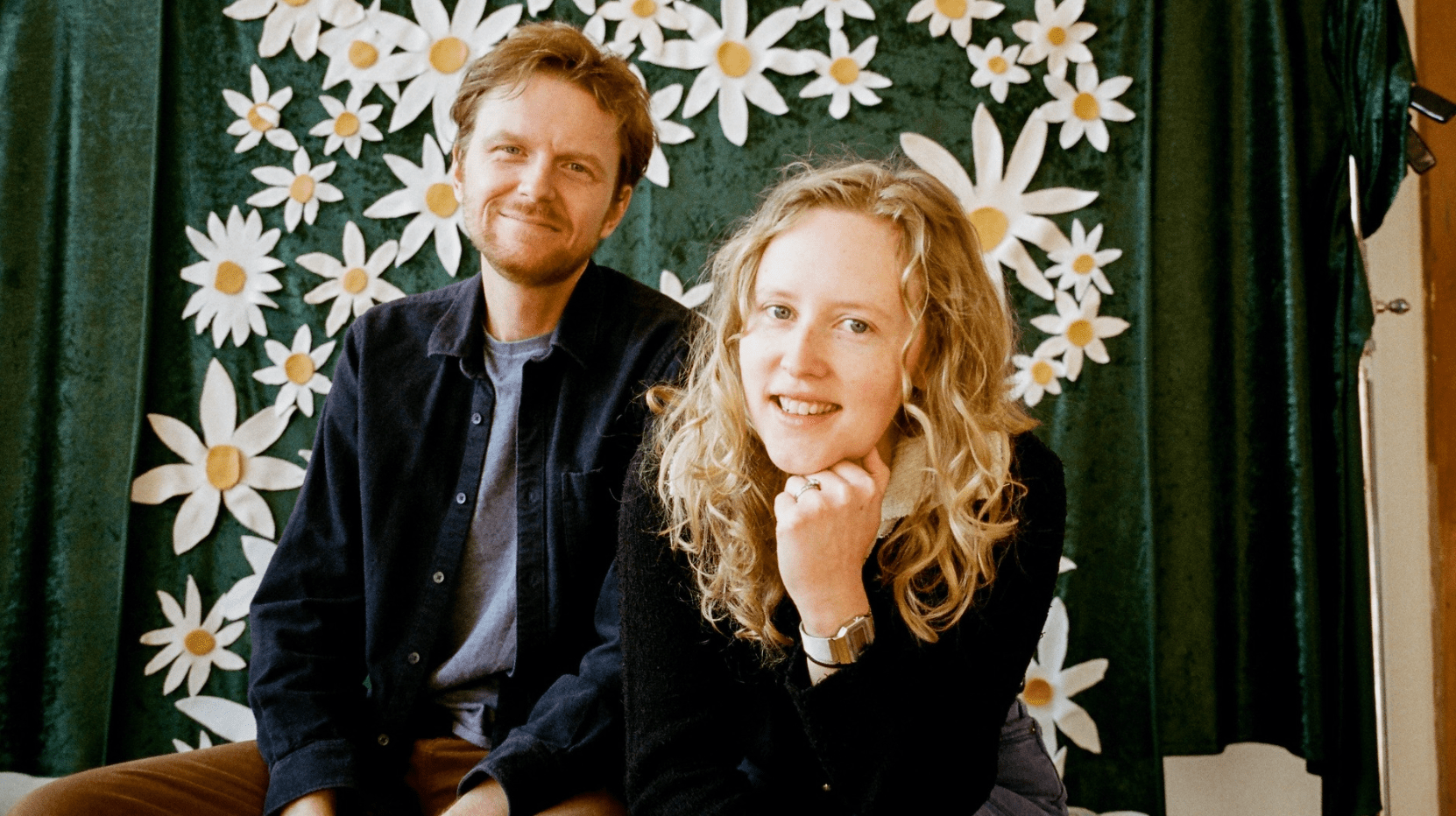

The first painting was a secular Hail Mary. In December of 2023, Minneapolis-based tattoo artist James Gunn learned his aunt back in Melbourne—his legal guardian during his formative and at times rebellious teenage years—was in an induced coma following a bone marrow transplant. He’d been meaning to call, but time had slipped by.

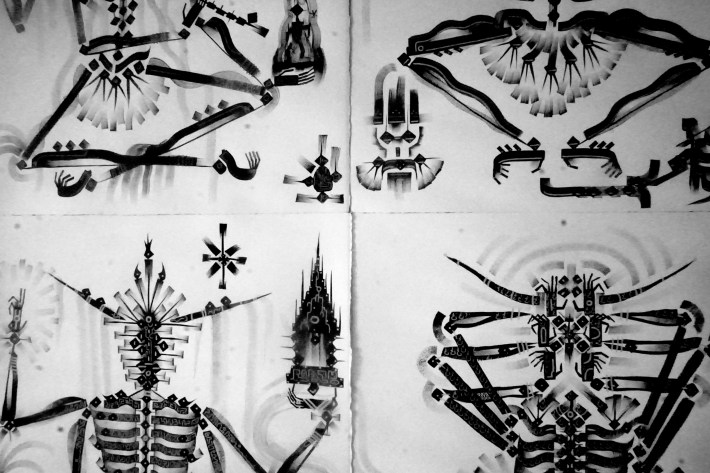

“I was struck not only by my own selfishness, but the reality that I might have missed the chance to let another human know how impactful they’d been,” he says, seated in the back booth of Dogwood Coffee on Lake Street. So, he sat down at a folding table in his bathroom and began to paint. Three weeks later, he’d made 99 paintings that have since been compiled into a book, available now from Gunn’s publishing company Unknown Characters.

The title, Good Luck with Your Demons, was born of an off-the-cuff farewell from a client. Gunn, who’s worked at Sea Wolf Tattoo Company in Powderhorn for seven years, didn’t conceptualize the paintings as demons, but their earliest viewers did, and he went with it. We sat down to discuss the book’s origins on the same day the first shipment arrived.

Racket: When were you first possessed to paint demons?

James Gunn: I guess I’ve always been fortunate to have a series of what I would call unusual experiences.

I thought you were going to say mental breakdowns.

No, this is the first of those, I think. [Laughs.] It was the least rational I’ve ever approached something. It was December 2023, and the system of order that I understood the world to operate with had completely broken down. The paintings sort of embody this philosophy that the only limitations we really have are often self-imposed. Belief rather than reality. Also, making something that was intensely personal, but resonated with other people, was reconnecting. I retreated from this idea that there’s any sort of universal human experience.

My abstract painting benders have been similar. For me, it was about the rejection of intellectualism and incumbent systems of knowledge. And needing a space where I could do whatever I wanted and not have to explain it to anybody.

Yeah, that’s the other thing. The process was like, push all humans away, then pull them back. I described my children as my only tethers to reality at that point. It was the most intense three weeks I’ve ever had. [My wife] could see it on me. She’d seen it on me in smaller ways before, but she could just see the itch. She was like, just go and do it.

Painting these was very abstract. Most of the time I’m making them on a folding table in my bathroom. And my bathroom is set up weird. It’s attached to my bedroom but there are no doors. It’s just got a wall that goes three-quarters of the way up to the roof. It’s separate but also very connected. I didn’t want to be alone while I was making them. There were a lot of moments of: I like this so much that I could disappear into this forever.

But you didn’t. Why didn’t you stay in the bathroom forever painting? I feel similarly about the year I started my novel. It was the happiest I’ve ever been and the least attached to reality. I had friends who were worried about me because they said my attachment to reality didn’t exist anymore. And it didn’t, but that was the assignment.

You can’t say that anything is possible and say there is an objective reality. And that’s kind of where I find myself now. It blows my mind that there’s going to be a book showing up at some point between now and 5 o’clock that I’ve never seen. And I’m terrified I’m not going to like the paperweight. [Laughs.]

When did people start getting the “demons” tattooed?

I would say within a month. Pretty quickly I realized that the way I was painting them could be tattooed. The chisel tip is something that I’ve always loved. It comes from when I was young. The cheap spray cans had a fan chisel tip so all the coolest tags I would see growing up were drawn with that. I use a fat brush, and any line width is just turning the brush. I tried to preserve the intensity and the spontaneity and the lack of intentionality. And I think the paintings relate to tattooing in the ritualistic way too. It’s a traditional cultural practice. Humans have been modifying their bodies like this for forever.

It’s not that deviant.

It’s not deviant or rebellious.

It’s not that deep.

It’s rebellious to engage in the same cultural practice that we did in the caves? How is that rebellious? That’s continuity.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.