No knock on John Mellencamp, who at 73 was out there singin’ the best he can with his ravaged pack-a-day voice, but it’s a little, I dunno, dispiriting to hear a football stadium crowd, average age likely past its 40s if not 50s, full-throatedly advising someone (our younger selves?) to “hold on to 16 as long as you can” because soon “the thrill of living is gone.” I mean, jeez, I thought we were all having a pretty good time here, guys.

Anyway, the three performers who followed Mellencamp to close out Farm Aid 40 at Minneapolis's Huntington Bank Stadium on Saturday were stalwart examples of how to remain vital in old age without feigning eternal youth. But we’ll get to Willie, Neil, and Bob soon enough. I had to wait a full day; you can hold on for a handful of paragraphs.

Much of the afternoon on the University of Minnesota campus was given over to relative youngsters, and everyone there could tell you their fave. I’ve always been partial to Waxahatchee’s Katie Crutchfield, who, as usual, delivered gorgeous stuff. Maybe you got knocked out of your Birkenstocks by topical, tousled TikTok troubadour Jesse Welles, who, sorry, strikes me as the Andy Borowitz of folk. (I’m glad he calls out Monsanto, but as someone who had a tumor eradicated three years ago, “Cancer is as lucrative a business as war/So if you ain't expecting peace, then why expect a cure?” smells like cynical horseshit to me.)

And now let me single out Farm Aid junior board member Margo Price, who represents the organization’s future. From the first note of “Don’t Let the Bastards Get You Down,” her set kicked every ass within range of her boots, and she carries on the legacy of the old guys who followed her on stage more honestly than any male contemporary, that’s for damn sure. She rocked Waylon’s “Kissing You Goodbye” (preceding line: “Get your tongue out my mouth”), made her point with “Deportee” (“A song that Woody Guthrie wrote 100 years ago,” she said, and it’s crazy that the math checks out), and, to close her set, brought out two of her fellow kids, Welles and Billy Strings, to tackle Dylan’s “Maggie’s Farm.” Though I wish she’d spend a little less time revisiting the old fellas and do her own thing, I understand why she doesn’t. They were a lot of fun to hang with this weekend.

But I’m not here to do a blow-by-blow—the music started at 12:30 p.m. and ended more than 12 hours later, and I just might have napped in the press box during one set (I’m not saying which). Music aside, there was more to this event than anyone could take in. You could have spent a full day in the “Homegrown Village” where farmers and agricultural activists spread the message of Farm Aid, which is an organization as much as a concert, a message honed and diversified over the past four decades.

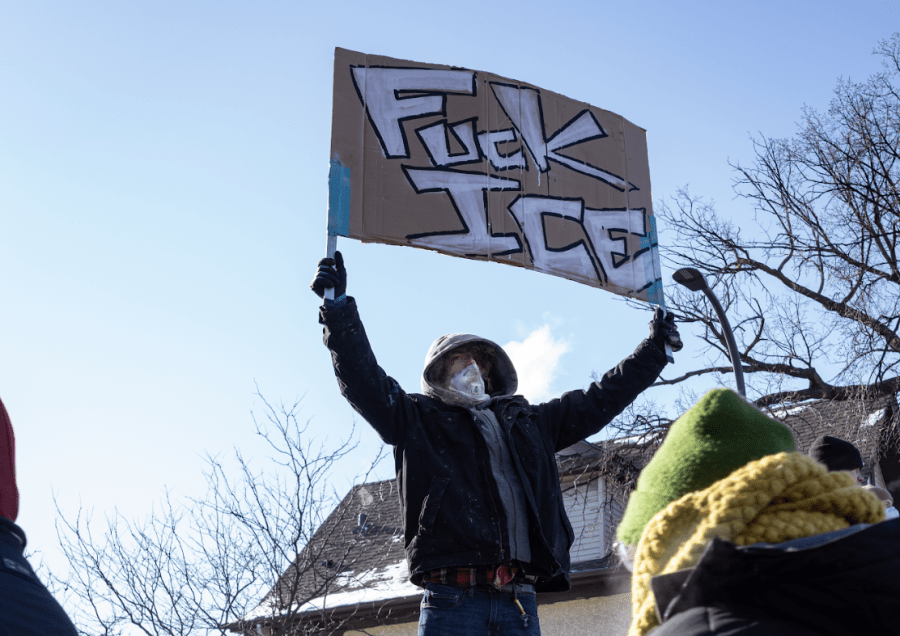

Whatever the aggregate politics of Minnesota’s farmers, the mood at Huntington was palpably liberal, if not leftier. Though several politicians popped up on stage, no Republicans were in the house, unless you count Rep. Angie Craig—getting to boo her as she pretended to care about farmers more than cops was as thrilling as getting to hear Dylan sing “All Along the Watchtower.” And when Gov. Tim Walz introduced Willie Nelson, nigh on midnight, the response was overwhelmingly positive.

Still, the spirit of the politically fraught ’80s pervaded the event. It was Mellencamp’s “Rain on the Scarecrow,” which he pounded through, that taught this Jersey teen about what’s commonly referred to as that decade’s “farm crisis.” (Though as Steve Earle pointed out during his set, that crisis has been pretty much ongoing since.) And it was, of course, Dylan who somewhat petulantly suggested that American farmers needed money as badly as starving Ethiopians while performing at Live Aid.

Dylan had been lost for much of the ’80s, peevishly Zionist, pedantically superstitious, and just plain grumpy about women. Neil’s label sued him for allegedly sabotaging his own career, but he was honestly more upset about beer commercials and the Panama Canal. (Ask your parents.) The ’80s were sweet to Willie, as he became a crossover pop star and a staunch left counterbalance to Nashville conservatism. All three men have come a long way since then, and at Farm Aid 40 they all looked back at where they’d been.

Bob Dylan is no dummy. He must know by now that the harder he tries to hide the harder we search him out. Nonetheless he concealed himself in a black hoodie, behind a piano, on a dim stage for his first Minneapolis performance since 2014, his three band members clustered conspiratorially around him, like they were about to chant “light as a feather, stiff as a board.” Even on the Jumbotron, you had to hunt for him.

The consensus among the sloshed boomers in my vicinity on the stadium floor was that Dylan’s set was “weird.” Which I mean, yeah, I guess, compared to the reheated soul of Nathaniel Rateliff, whose earlier appearance on stage one woman, after loudly complaining that Dylan hadn’t played any “political” songs, said she strongly preferred.

But what’s so weird about a guy who just likes working up new arrangements of old songs and lets you listen in? Figure it’s Dylan’s version of jazz—tinkering with the oldies to figure out what makes them tick, yanking ’em this way and that to expand their parameters without obliterating their identity.

I get that such a process may not be to everyone’s taste, especially at 10 o’clock on a Saturday night, but there was nothing particularly enigmatic about Dylan’s 20-minute set. An initial jumble of piano, guitar, and cymbal eventually coalesced into “All Along the Watchtower”—If you were looking for a nod to his days in Minneapolis, maybe here it was. Only Bob knows for sure if that tune was truly inspired by the Witch’s Hat in Prospect Park, but he certainly knows folks think it did. And, later in the set, “Highway 61 Revisited”? Why, I’ve driven on Highway 61!

Best not to read too much into any of this, though. Dylan had played all five songs the night before in Wisconsin, and they’ve been part of his regular set for months. Better just to appreciate the vocal ingenuity of a guy seemingly committed to never phrasing a lyric the same way twice. He sounded wounded but alive on “I Can Tell,” a Bo Diddley cover he hauled out first in June, a chance for him to relive his high school rock ‘n’ roll piano dreams. “To Ramona” was now a dusty bordertown waltz, piano and voice landing insistently on the beat. Finally, “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” just floated along, the drums underneath particularly impressionistic. No one had ever run away from his past so slowly.

Then again, Dylan did omit “Masters of War,” which he’s been opening his set with for over a month. Maybe that Night Sweats fan was on to something. Wait, was Bob Dylan going out of his way not to make a statement? Take it to the message boards, fellas.

Neil Young, for better or worse, seems constitutionally incapable of not making a statement. An inveterate crank, and I say that ever-so-lovingly, the jowly, yowling, cacophonous lummox shoots only one way—from the hip—and the best you can hope for is not to catch a stray. You don’t listen to Neil Young because he’s right; you listen to him because you’re the same kind of mad.

With his gray mutton chops, cap, and flannel shirt, Young looked every bit the retired train engineer he would have been in another life. (Neil's a big-time foamer.) He stomped into the fray with “Big Crime,” which is not shy about shouting the “F” word. “Don't need no fascist rules/Don't want no fascist schools/Don't want soldiers walking on our streets/Got big crime in DC at the White House”—those are four sentiments I appreciate even if I think protest songs should have catchier tunes.

Still, if Neil’s eloquence and craft have subsided with age, his orneriness hasn’t, and rock 'n' roll sure needs one of those qualities more than the others. What mattered most about Young’s set was the unkempt noise he left in his wake. There had been so much acoustic virtuosity throughout the day, with neo-bluegrassers like Trampled by Turtles and Billy Strings moving their fingers in remarkable, unduplicable ways. But Young’s hands flailing roughly against his guitar, manhandling strings till they squawked in anger or desperation, spoke more to me, and to our moment.

Young’s latest band, the Chrome Hearts, includes three (relatively) young fellas—Willie’s son Micah, as well as Corey McCormick and Anthony LoGergo, from Willie’s other son Lukas’s band Promise of the Real—as well as 82-year-old Muscle Shoals veteran Spooner Oldham, who was wheeled on and offstage by nurses. They kept pace with their geezer-in-chief, and LoGergo in particular has a valuable lead foot on the bass drum. Call ’em Crazy Foal.

Much of Young’s set was given over to his older political songs, which suited the present moment to varying degrees. When Neil dropped “Rockin’ in the Free World” in 1989, targeting the hypocrisy of the elder Bush, we were all just relieved that the former Reagan fan was now quoting Jesse Jackson. Who could have predicted it would become such an anthem of flustered persistence?

For the 1987 song “Long Walk Home,” about where America had first gone wrong (maybe it was the slavery, or, you know, the genocide), Young changed the lyric “from Vietnam to old Beirut” to reference Canada and “old Ukraine.” And during a timely “Be the Rain” (it was drizzling), Young sang alternately through two mics, one of which sounded like a tinny supermarket loudspeaker. Message: “We’ve got to save Mother Earth.”

Gotta say though, it did not feel appropriate to revive “Southern Man” up north at a time when racism has been clearly a national crisis in places very much like Minneapolis. Yet the crunching “Hey Hey, My My (Into the Black)” sounded as righteous and crotchety as ever, even if we all wish Johnny Rotten would have faded away by now. And he closed with “Old Man,” a 79-year-old re-inhabiting the voice of a 24-year-old gazing across the generation gap at his future self.

Many of us think Willie Nelson can never die, but that’s a much harder belief to hold when you see the man close up on a giant digital screen. Especially after you’ve just watched the 1986 video for “Living in the Promiseland,” which played before Willie’s set, and seen the man as he was 40 years earlier. Again, we were back in the ’80s, this time for a number one country song that quoted Emma Lazarus and celebrated immigration, its video featuring the Statue of Liberty and Haitian boat people. The message was clear: This ain’t just about farms. It’s about people.

You don’t turn to Willie for surprises, and of course he kicked off his set with “Whiskey River,” as he has for more years than I care to check. I’ve heard reports that he’s seemed frail in recent shows, but he was a hale 92 on Saturday night, especially considering that he came on stage after midnight. He’s certainly more alert than many THC abusers a third of his age. Keep in mind this was a man who played a concert over 300 miles away in Wisconsin the night before and had to roll out for an 11 a.m. press conference.

If Dylan is constantly rummaging through his back pages for compositions to reconsider, Willie, despite his hefty songbook, always returns to a few favorites. Among these are the minor-key, Spanish-tinged “I Never Cared for You,” where he accompanied himself with a flutter of irregularly punctuated guitar chording, the lovelorn “Angel Flying Too Close to the Ground,” and “Georgia (On My Mind),” which he and Ray Charles will someday have to flip for if Willie ever joins him on the other side.

As a performer, Willie is now a man negotiating his limitations, if you can even call them that. He’s not ashamed to speak through brief passages, but he’s still never a lazy singer; he phrases as thoughtfully as ever, never hits a bum note. You could say the same for his guitar work, though there were rare moments when his fingers couldn’t quite keep pace with his intentions.

And he wasn’t afraid to let others shoulder some of the weight. Sons Lukas and Micah were on either side of him for guitar and harmony duties, while, as ever, harmonica ace Mickey Rafael was on hand, playing beautifully and sometimes a little too much. Willie brought out singer Lily Meola to sing “Will You Remember Mine,” and he handed “Help Me Make It Through the Night” off to sideman Waylon Payne, whose mamma Sammi Smith had made that Kris Kristofferson number a big hit. Willie even gamely sang backup on Micah’s “Everything Is Bullshit.”

Of course Willie knows what we’re all thinking when we look at his fragile arms and puffy face, and he knows how to milk pathos from old age. “I’m the last leaf on the tree,” he sang proudly yet delicately late in his set, but he wouldn’t leave us on that somber note—next came “Roll Me Up and Smoke Me When I Die.”

From there, the set was one false ending after another. Willie was joined by the whole Farm Aid cast (excepting, of course, Mr. Dylan) to sing “Will the Circle Be Unbroken,” which turned into “I’ll Fly Away,” both such indelible standards you could almost forget they’re about death. And then, an all-star singalong to Mac Davis’s cornball “It’s Hard to Be Humble.” Would have loved to hear Bob chime in on that.

Finally, closing in on 1 a.m., Willie actually ended the show with “I Saw the Light,” just the way that Hank woulda used to done it. The life he loves really is making music with his friends.

I happened to see Seven Samurai at the Heights on Sunday, memories of Farm Aid fresh in my mind. An elder samurai is recruiting others to help protect a farm village, and in joining him another samurai tells him, “Although I understand the farmers' suffering and understand why you would take up their cause, it's your character that I find most compelling.” Of course I thought of Willie Nelson.