“We used to say there was an imaginary line between Kamarczuck’s and Nye’s,” says Doug Padilla, Minneapolis artist and cofounder of Art-A-Whirl. “We called it ‘the sausage curtain’ because people from downtown would not come further into Northeast—they felt it was too dangerous.”

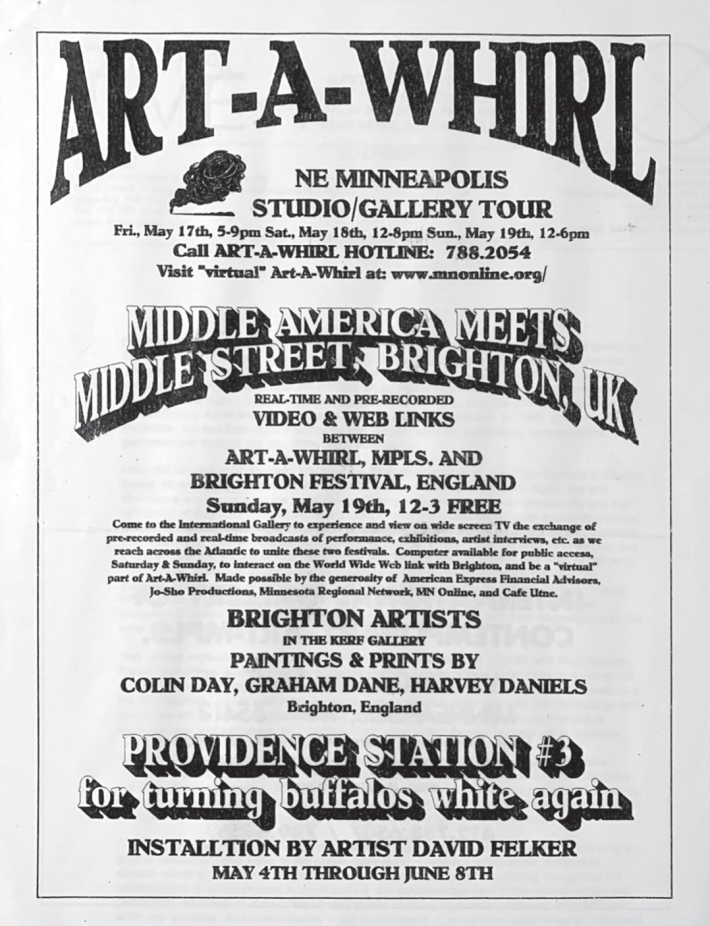

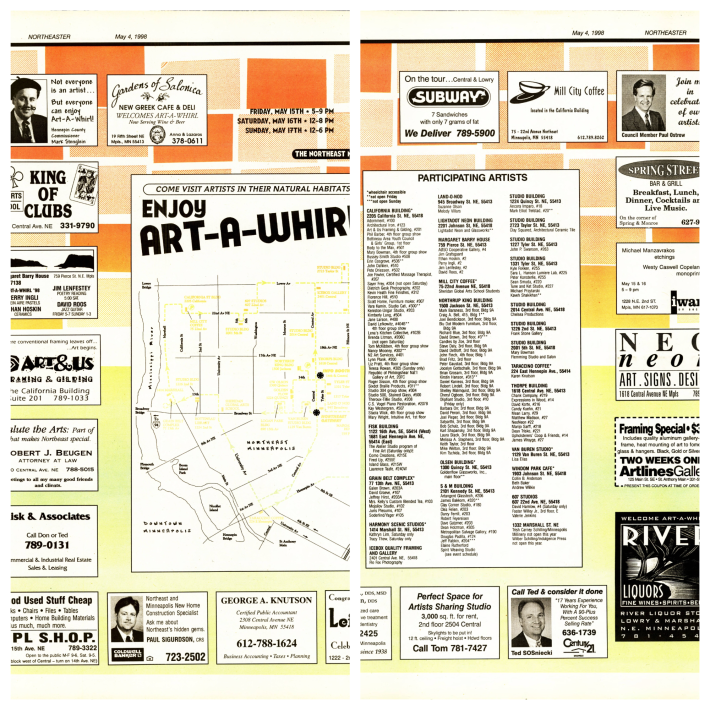

Northeast doesn’t have that problem anymore. These days, you can hardly walk through the neighborhood of packed breweries and cafes without hearing murmurs about the upcoming Art-A-Whirl. The annual open-studio tour boasted 1,300 participating artists and galleries last May as art enjoyers from all over the country flooded the streets of the Northeast Arts District to commune with artists, enjoy a Flavorwave IPA from Indeed, and thrash along to Marijuana Deathsquads. Now in its 30th year, Art-A-Whirl has become the largest open-studio tour in the country.

But at the festival’s inception in 1995, northeast Minneapolis looked very different. How did Art-A-Whirl grow to become one of Northeast’s most famous traditions? It took the vision of a renegade group of artists and community members who were present for the festival’s edgier and wilder days. And this year, in honor of Art-A-Whirl’s 30th anniversary, we pay homage to the history and hijinks that paved the way.

In the ’90s, Minneapolis’s de facto “arts district” was across the river from Northeast, in today’s North Loop, then known as the Warehouse District.

“Once they built the Target Center, it changed all the galleries that were in the Warehouse District,” says Howard Christopherson, owner of Icebox Gallery and another cofounder of Art-A-Whirl. In 1988, Christopherson’s original downtown studio in the Century Camera Building was demolished, along with hundreds of other arts spaces, to make room for Target Center’s parking ramps. “My studio mate and I went looking in the newspaper for the biggest space and the cheapest price, and we found this basement space on Central,” he recalls.

Stories like Christopherson’s are commonplace. Padilla moved his gallery out of downtown that same year, becoming the first artist in what is now the Casket Arts Community. At the time, the Casket Arts Building was still occupied by Northwestern Casket Company and was actively manufacturing coffins. “The neighborhood asked them to only load caskets at night because they didn’t like seeing them during the day,” Padilla chuckles.

He rented a space in a carriage house behind the present-day Casket Arts Building, which was occupied by a company that made prison equipment and furniture. “The killer was, everybody working there was an ex-con,” Padilla says.

Heidi Andermack, former president of the Northeast Minneapolis Arts Association, recalls how Hai Hai, the trendy Vietnamese spot on University, used to be home to the infamous “Deuce Deuce”—aka the 22nd Avenue Station strip club— and how many vacant storefronts were taken advantage of by accountants peddling seasonal tax services. But inside many of those seemingly empty buildings, art was being made and shared.

Paul Ostrow became familiar with the migration of the Minneapolis arts scene during his 1996 campaign for Minneapolis City Council.

“It was a bit of a secret, at least to many, that there were these buildings that were being transformed,” he says. “There were all these creative people in them. It was an underground movement—some of these buildings didn’t have the right code to have artists in… some of the artists were even living in the buildings, and that had created some concerns.”

As Padilla recalls, “In those days, they were trying to get rid of us! The cops especially. Northeast was not pro-artist. They used to bust our openings a lot—I suppose because we had music and stuff. But artists always need community; they need their art to be seen.”

And artists were still struggling to get their work seen—and sold—in this new neighborhood.

“It was a long learning curve to get people to understand that there was something happening in Northeast,” Christopherson says. “The early days of the art scene used to be galleries downtown, so when I first moved to Northeast, I really had to struggle to get people to come up here.”

“Prior to Art-A-Whirl, the neighbors and community weren’t exactly embracing us yet,” remembers Jennifer Young, co-owner of the California Building. “They were a little uneasy about what goes on inside of that big warehouse—maybe a little scared. There were different people doing different stuff and it wasn’t quite understood.”

That would begin to change after a fateful meeting in the winter of 1995. Padilla, Christopherson, and several other artists were gathered in a studio in the Thorp Building by David Felker, an artist who had recently moved to town from Alaska. During his tenure as the director of the International Gallery of Contemporary Art in Anchorage, he had started an open-studio tour and saw an opportunity in Northeast for similar success. His fellow artists weren’t so sure.

Dean Trisko attended that initial meeting. “A lot of us, including myself, were like, ‘What’s an open-studio tour?’” he remembers.

“He had this idea and at first some of us were a little jaded about it,” Christopherson says. “Because he wanted to get money from the city. We were like, I don’t think so.”

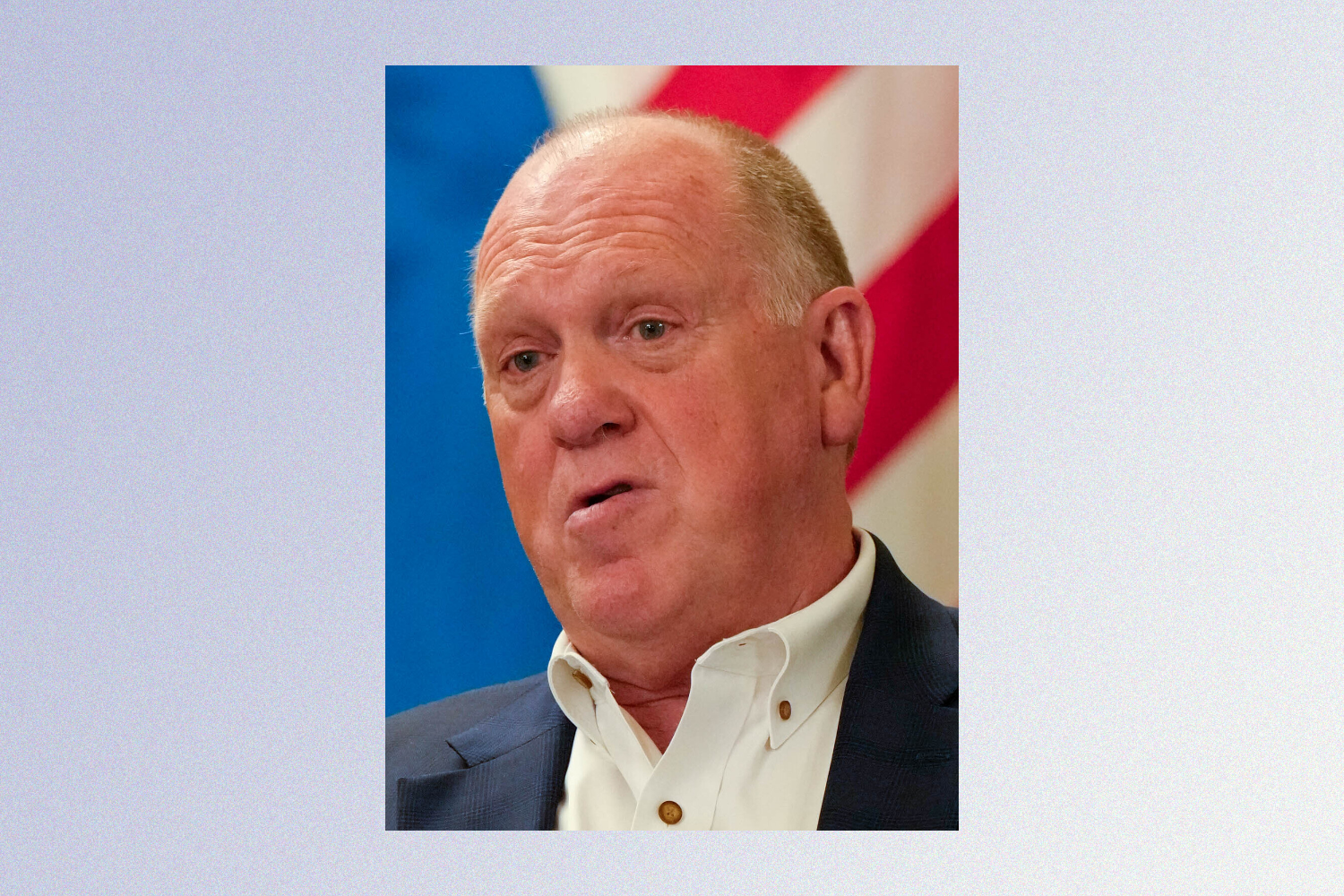

In 1995, Northeast’s representative on the Minneapolis City Council was born-and-raised Northeast resident Walt Dziedzic. Dziedzic had gone to school at Edison High School, taught at DeLaSalle High School, and was an officer for the Minneapolis Police Department before he was elected to the city council.

“He was a character,” says Christopherson, who had history with Dziedzic. “In the early ’80s, I had to go in front of him while he was on the park board. I made a sculpture out on the island in Powderhorn Park, and he was the only dissenting vote.”

“He was like the mayor of Northeast,” Padilla says. “He was very old school; conservative for a Democrat. Dave Felker said, ‘We should get Walt Dziedzic on our side!’ and I said, ‘No, that’s really stupid, Dave.’”

Somehow, though, Felker talked Padilla into it. “The next thing you know, I’m in Walt Dziedzic’s Cadillac and he’s driving me around Northeast, showing me where he grew up and played baseball and went to grade school,” Padilla says. “I was suddenly his best friend because it dawned on him that artists were his new constituents. That’s who was moving to Northeast. You could see the lightbulb go on in his head.”

“He believed in us,” Young remembers. “And that surprised everybody. He was the kind of guy who loved his neighborhood, and he saw the writing on the wall of what was happening in his neighborhood: Artists were here. Instead of fighting it or fearing it or pushing against it, he decided to dive in on it.”

“In one week, suddenly, we had like 25 grand in funding,” Padilla says. “He just made it happen. Suddenly, we had buses and bus routes taking people from building to building. We had money for publicity we could print out. Walt made a big difference that first year. Plus, he went around to the cops and everybody and said, ‘Leave these people alone. This is the future.’”

Luckily, at that very first meeting, the crew had already decided on a direction for branding.

“In the course of this meeting, this one guy, Juris, walks off to go to the restroom and looks out the window across Central,” Christopherson says. “There was a business over there with a logo that had been there for a long time called Whirl-Air Flow. So he comes back and goes, ‘How about Art-A-Whirl?’ And I just had learned real close to that time that a Tilt-A-Whirl was made in Minnesota, so I said, ‘Oh, that’s cool! I’d vote for that!”

“I said, that’s it!” Padilla says. “Some of us just went, ‘That’s it! That’s it!’ And then there was more arguing, because some people wanted a more formal name. We had a compromise: We decided that Art-A-Whirl would be the name of the event and Northeast Minneapolis Arts Association, NEMAA, became the name for the organization.”

With a catchy name and the support of the city, the artists began holding regular meetings to flesh out this idea of an open-studio tour. But when so many creative minds gather in one room, there are bound to be disagreements.

Christopherson remembers how, at one planning meeting, an organizer attended in a full Mafioso costume—he was attending a costume party later that evening. In the usual fashion of these meetings, the group was arguing logistics.

“He reached in his pocket and pulls out a fucking Glock,” Christopherson says, “which he was just using as a prop! I remember Dave Felker reaches over and grabs it. David was in the military, so he grabbed that gun right away and he knew how to cock it real fast, and he looked to make sure it was empty. He goes, ‘What the hell did you bring that thing in here for?!’”

“Those first years were more wildflower than cultivated,” Padilla says. “We had great parties.” Art-A-Whirl’s debut in 1996 boasted 150 open artists’ studios across 21 buildings in Northeast.

In those first several years, artists worked hard to stretch the funds they got from the City Council as far as they could. “We made signs of the tornado logo and somebody made stencils,” Christopherson says.

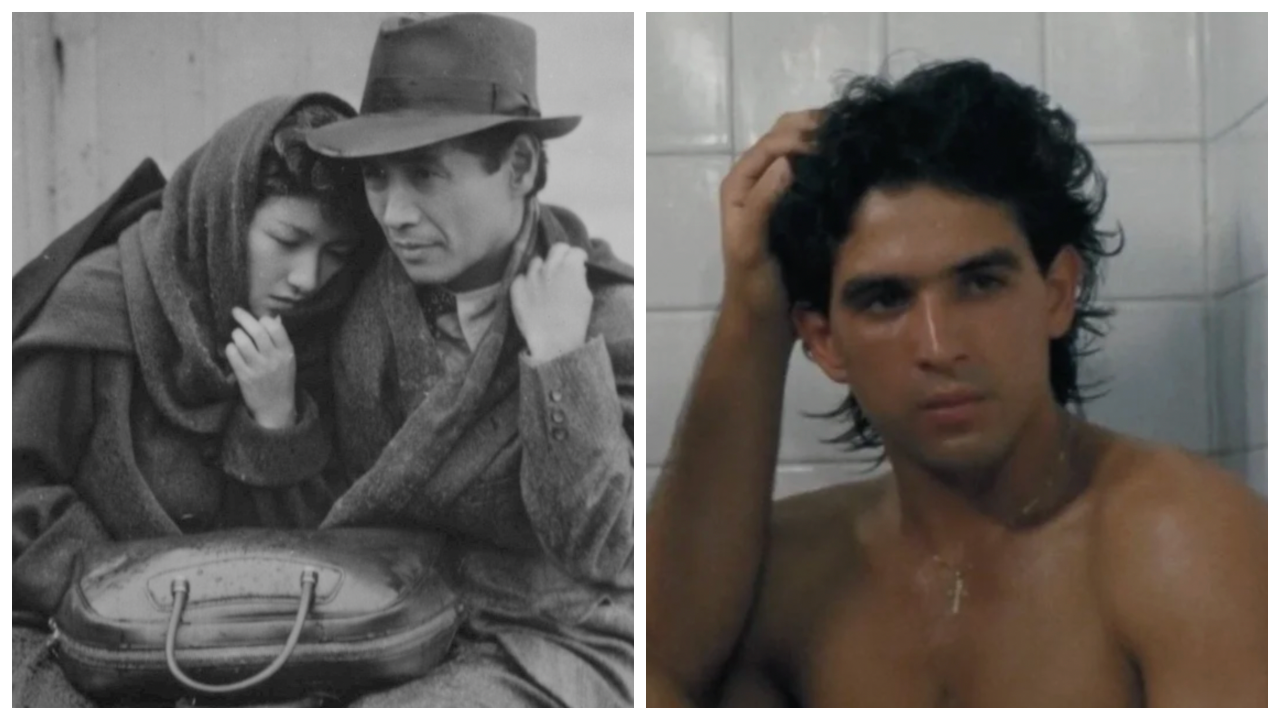

“The biggest challenge with Art-A-Whirl came in year two or three,” Trisko says. “Dave [Felker] had moved out of the state, and none of us knew exactly what Dave did in the background—he kind of handled the promotion and everything. Year two and three was very much ‘make your own publicity.’ We got some pro bono help from professionals, but for the most part, it was spray painting signs and putting up plywood sandwich boards and things like that.”

During their search for publicity, the crew had managed to secure a space on a local news station in 1998. At 5 a.m., while eating breakfast, Trisko received a phone call. The woman on the other end was from the news station, grateful to have caught him via landline before he headed to the station.

“She says, ‘Maybe you haven’t heard, but Frank Sinatra died,’” Trisko recalls. “I’m like, ‘Oh… okay. We weren’t close…’ and she says, ‘No, Frank Sinatra died. Your segment is cancelled. Everything’s cancelled! It’s all Frank Sinatra today.”

That same year, Trisko had also been working with the Sheridan School to put on a music and dance showcase on Art-A-Whirl’s opening night.

“I became their liaison for NEMAA,” he says. “We got a whole bunch of kids to do the kickoff of Art-A-Whirl, and there is a tornado warning. I am the one who has to decide: Are we going to cancel or go? I had been in charge of all of the things: food for the kids, a bandstand for them to perform on, lighting… So we cancelled a half hour before the event because of the tornado warnings. What I always find humorous and ironic is our logo is a tornado.”

The next day, Saturday morning, Trisko secured a slot on WCCO to talk about how Art-A-Whirl had been affected by the storm.

“In those days, WCCO was like a weather-intense station,” he says. “All I want to talk about is, ‘Art-A-Whirl’s gonna be going on today! It’s gonna be great!’ and they’re like, ‘So what did you see for trees down?’”

This tornado is a legendary mascot among the early Art-A-Whirl mainstays. “The building got dark,” Young says of the California Building. “People could see the funnel clouds coming in from the west out of the sixth floor windows here. We lost power and people had to descend the building.”

“Everybody went dark,” Padilla says. He remembers these power outages well: “Over at the Tyler Street buildings, they had put up a show in the halls and they were gonna have bands. They lit candles and did the whole show by candlelight and had all the bands play acoustically. We had a wonderful evening.”

Andermack remembers that a friend of hers known as Chank had been affected by the tornado. “He had bought hundreds of hot dogs to barbecue outside of the Thorp Building,” she says. “And we had to put them in the freezer and have backyard barbecues all summer long eating hot dogs from Ready Meats.”

Shortly after the festival’s inaugural year, Dzeidzic stepped down from his 22-year career as Northeast’s representative on the City Council. He was succeeded by Paul Ostrow, who continued the work of supporting the new residents of Northeast. The Star Tribune reported that 1998’s Art-A-Whirl hosted 200 open artists’ studios, and that number continued to grow year after year.

It was Ostrow who drafted the resolution in November 2002 that officially named the Northeast Minneapolis Arts District. Since then, Art-A-Whirl’s partnership with Northeast only deepened. In 2003’s Whirl, Dzeidzic led a “Walt’s World Tour” to show off the newly minted Arts District. Traffic and parking agreements were formed with local businesses. Breweries and bars began hosting events to capitalize on the new traffic. The festival had become a hit.

This May during the 30th Art-A-Whirl, as folks revel in the polished veneer of present-day Northeast, remember the renegades wild enough to build it. Swing by Dzeidzic’s memorial avenue on the corner of Arthur Street & 18th Avenue, or stop by the brand-new Arts District Welcome Center in Timber and Tie on 14th Avenue. Keep an eye out for 1515 Central Ave., the building Juris Plesums saw when he named the event, whose Air-Flow logo has now faded.

Explore the buildings and streets that, though polished now, have so many stories to tell of the grit and vision artists have proven is capable of changing the face of a neighborhood.

“There is still some of the randomness to Art-A-Whirl,” Trisko says. “But to me, the biggest thrill is having new people come to my studio to see my work. It really is, at the core, what’s exciting about the event. Art isn’t fully realized as a creation until somebody looks at it and takes it in.”