“I am bothered by the polarization in the GLBT community,” Mike Bolton wrote in the May 24, 1995 “Letters” section of focusPoint, a Minneapolis-based queer periodical from the mid-1990s. “I see essentially two camps: the ‘equal rights not special rights’ people … and those who consider themselves significantly different from mainstream society.”

Bolton continued: “I believe in order to make strides for GLBT rights we have to present a united front, but the two camps may be inherently divergent.”

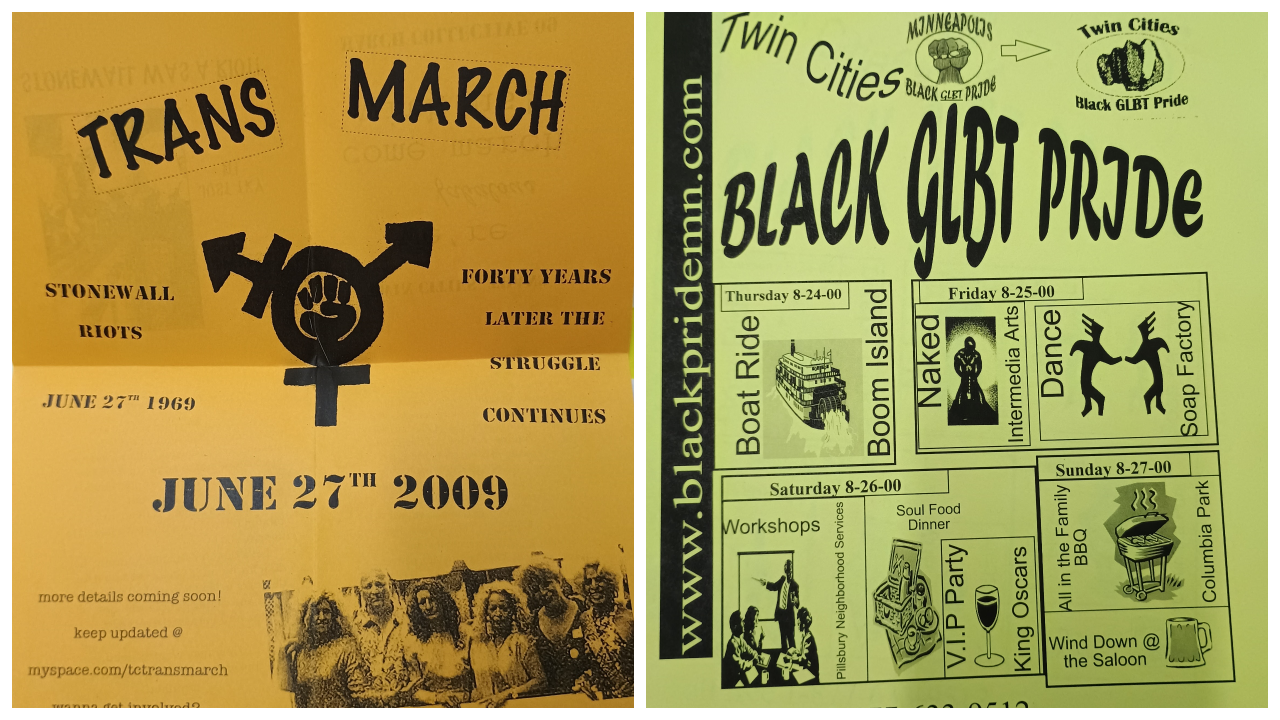

Each June, LGBTQ+ people in the Twin Cities and around the United States celebrate Pride Month. The timing commemorates the 1969 riot at New York City queer nightclub Stonewall Inn, generally considered to be the flashpoint that kicked off the modern movement for queer liberation nationwide.

But almost as long as people have been celebrating Pride, there have been divisions like the ones Bolton refers to in that 30-year-old letter.

“It was a debate at every Gay Pride demonstration from the very beginning about who we included in the Movement and who was legitimately in the Gay Movement,” said Koreen Phelps in a 1993 interview with the Twin Cities Gay and Lesbian Community Oral History Project.

When most people think about Twin Cities Pride, they think about… well, Twin Cities Pride—the big parade and festival that will take over Loring Park this weekend, as it has since 1972. But numerous other Pride celebrations have emerged either in opposition of or as a compliment to Twin Cities Pride over the years.

The Early Years and the “Great Schism” of 1982

Phelps, who founded the organization Freedom of Repression of Erotic Expression (FREE) at the University of Minnesota in 1969, related a contested political dynamic behind the scenes of the early Pride celebrations in Minneapolis.

“The real inspiration for those early marches came out of FREE,” Phelps said in that 1993 interview, and even early on, there were internal divisions between political engagement and community building. Some people “just wanted to stay with gay rights issues” and focus on social activities, according to Phelps, while others wanted to become more involved with feminism and anti-war activism. Some of those early divisions—between gay men and lesbians, social activities and political demonstrations, marriage and nonmonogamy, assimilation and anti-conformism—persist to this day.

In an interview for the Minnesota Lesbian Community Organizing Oral History Project, Candace Margulies described another long-lasting division within the queer community. Margulies, founder and first coordinator of A Woman’s Coffeehouse, noted that “women and lesbians weren’t being involved or invited or included in Gay Pride” in the celebration’s early days.

Karen Hogan, head librarian of Quatrefoil Library, agrees. Hogan, who visited and then moved to the Twin Cities in the 1980s, tells Racket that for much of the 1970s and into the 1980s, “lesbians seemed to live in a different sphere from gay men.”

Women “had other items on their plate that they hoped would become issues over time,” like abortion rights, the ERA, and the prevalence of sexual violence, Dennis E. Miller said in another interview for the Twin Cities Gay and Lesbian Oral History Project.

And the separate spheres were in some senses geographically literal. Downtown was associated with gay men; Loring Park was chosen as the site of the first Pride parade because it was a well-known cruising spot near a number of bars that catered to gay clientele.

So, over in south Minneapolis, lesbians and queer women created a separate community. Take Back The Night—female-dominated gatherings that protested sexual violence—represented a sort of counterpoint to Pride protests, and there were a host of smaller organizations and gatherings, including “womyn’s only” coffeehouses, bookstores, sports leagues, support groups, and performance venues.

In 1982, the year of the “great schism” and the high water mark of lesbian separatism, Minneapolis had two separate Pride celebrations: Gay Pride in Loring Park, which drew around 1,000 people, and Lesbian Pride in Powderhorn, attended by about 400 (according to Equal Time, another queer-focused periodical from the era).

“Lesbians reacted with either friendly disinterest or outright condescension” to efforts by the Gay Pride committee to include them, wrote one commentator in Equal Time, so “for the sake of honesty we should return to the traditional title, ‘Gay Pride Week.’” Gay men are “jealous of the lesbian community!” retorted another writer.

But by the following year, lesbians and gays were united again. What changed? In the same June 1982 issue of Equal Time, a small bulletin on a mysterious but deadly disease appeared. AIDS brought the community together, Hogan says: “Gay men were under attack, getting sick, dying.” Reagan won the presidency in 1980; the deadly threat to queer Americans “meant we had to work together.”

Pride and Popularization

Through the 1980s and early ’90s, a more radical and diverse queer culture developed alongside Twin Cities Pride, which had gone mainstream by the mid-90s.

“It has grown from hundreds to a hundred thousand. It has lost much of the element of political struggle and fear of exposure. Now politicians come to the festival to ask for the gay vote, corporations come to appeal to the gay market,” wrote an opinion columnist in focusPoint.

River cruises were held annually, and a yearly beach party, held at a long-time cruising ground known as “Bare Ass Beach” on the banks of the Mississippi near Franklin and the River Road, attracted hundreds of attendees.

Some of the last flowerings of lesbian separatism bloomed in the form of the Twin Cities Lesbian Avengers, which held annual Dyke Marches beginning in the early 1990s. Coinciding with the rise of the Riot Grrrl scene, the mid-’90s were the heyday of the Dyke Marches, which continued on into the 2000s, but attracted dwindling crowds (though some cities still host Dyke Marches during Pride month to this day).

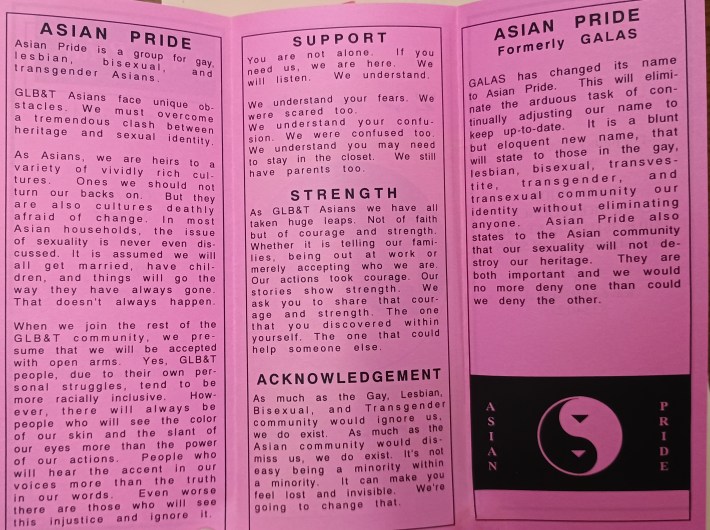

But as an earlier generation’s organizations began to fade away, new, multiracial and gender-inclusive movements began to emerge. One of the earliest, Womyn of Color Stirfry, emerged out of a “support group” for lesbians of color who struggled to find community in predominantly white lesbian spaces. In conjunction with IRUWA, the Minnesota chapter of the National Coalition of Black Lesbians and Gays, Stirfry gave birth to other groups: Voces de Amiente, Lesbians of Color Empowered Together, Black African American Dykes, Asian and Pacific Lesbian and Bisexual Womyn, and Minnesota Men of Color.

Many of these groups began to participate in Twin Cities Pride “to alert people that we were available,” said Stirfry cofounder Nancy Lee in a TC Gays and Lesbians Oral History Project interview.

In 1987, American Indian Gays and Lesbians, founded by Richard LaFortune in Minneapolis, began holding their own celebrations of indigenous sexuality and spritual traditions; these evolved into the International Two Spirit Gatherings. The Gatherings are held across North America, including Minnesota. For the last several years, as trans rights have increasingly come under attack, the New Native Theater has produced an annual Two Spirit Powwow with support from the Minneapolis American Indian Center. This year’s Powwow was held June 24.

In north Minneapolis, a vibrant Black Ball and cabaret scene flourished in the ’60s and ‘70s but was devastated by the AIDS epidemic. In the late 1990s, Black Pride (later MN POC Pride) revitalized the traditions of earlier generations. MN POC Pride, formed in the late 1990s, is affiliated with other Black Pride festivities across the nation.

Black Pride developed out of organizations that formed in the 1990s, like Minnesota Men of Color and Power to the People, and sought to provide a focal point for trans and BIPOC queer people within Twin Cities Pride. “Black, Indigenous, people of color often don't get the same stage time or the recognition. And they wanted something to be different,” said Rox Anderson, director of the Minnesota Transgender Health Coalition, in a 2022 interview with Minnesota Public Radio.

MN POC Pride maintains a “complex but respectful” relationship to Twin Cities Pride, according to LaTonya Noble, the organization’s executive director. “Mainstream Pride events often didn’t fully represent or address our specific experiences and struggles,” she says, while Black Pride festivities are “a way for us to celebrate our identities openly, build community, and advocate for issues unique to BIPOC LGBTQ+ folks.”

MN POC Pride’s concerns are reflected in Taking Back Pride, a protest within and against Twin Cities Pride. Following Philando Castile’s murder at the hands of Minneapolis Police officer Jeronimo Yanez in 2016, and his subsequent 2017 acquittal, Taking Back Pride was organized

as a protest against the presence of Minneapolis PD at the Loring Park Pride.

Over time, its focus has also expanded to include not just opposition to police at Pride, but to protest against the commodification of queer identity and the exclusion and marginalization of trans/non-conforming identities at Pride. “The history of Stonewall and the leadership of trans women of color against police brutality are all but invisible in today’s TC Pride’s parade,” the organization argues on its website.

The Trans March held its own commemoration of Stonewall in order “to protest transphobia within the queer community, particularly with the Twin Cities Pride Festival.” In 2010, Trans March organizers proudly proclaimed they had been “rimming corporate Pride since 2007.” Since the advent of Taking Back Pride, which explicitly centers trans queer people, the Trans March has become more associated with the Trans Day of Visibility, held on March 31.

The Taking Back Pride March, which will begin at 10 a.m. on June 29 at Sixth Street and Hennepin Avenue, will be led by trans/nonbinary/queer BIPOC elders and youth, BIPOC social justice organizations opposing police violence, and the families of those impacted by police violence.

A newcomer to the alternative Pride scene, People’s Pride has been held every year in Powderhorn Park since 2021. People’s Pride describes itself as “a non-corporate alternative pride,” and in conjunction with Taking Back Pride, it offers a younger generation their own way of understanding queer identity. This year’s People’s Pride will be held at Powderhorn Park on June 28 from noon to 4 p.m.

The event has grown over time, attracting larger crowds and drawing more donations from both participants and vendors for mutual aid (TC Trans Mutual Aid, Community Aid Network MN, Southside foodshare, MN American Indian Women’s Resource Center, among others).

In an interview for the Twin Cities Lesbian and Gay Oral History Project, Ashley Rukes, a transgender activist for whom the Twin Cities Pride Parade is named, was asked whether she believed that the massive diversity of people who consider themselves to be queer in some way actually make up a community. She responded that “positives have come out of the reaction to the negative forces that had been placed upon our community at large.”

In other words: through adversity comes unity and strength. We’ll need all we can get.

Many thanks to Karen Hogan and Kathy Robbins (librarians at Quatrefoil Library), Nicole Olila (collaborator at Quatrefoil and also the Iterative Librarian), Lisa Vecoli (former Tretter Collection curator and founder of the Minnesota Lesbian Community Organizing Oral History Project), and Aiden Bettine (current Tretter Collection Curator) for their help in researching this story.